Geneva’s Lakefront: 1904 and Today

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

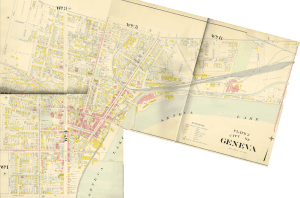

In my last post I discussed the 1873 birds’-eye view of the city that I used in a program this spring with Geneva third graders. We also looked at a 1904 Atlas of Ontario County in this session. Students loved deciphering the city’s past through these documents. After exploring these two maps in the classroom, we completed our exploration at Geneva’s lakefront at the end of May. We visited a few areas and compared them to the historical maps and photos of the places.

Today’s elementary students do not know a world without digital technology, online maps, satellite images, turn-by-turn directions, and instant communication of information. Nor do they or their parents remember when Geneva’s lakefront was not a place for recreation and enjoyment. Working with them on the lakefront reminded me how time can transform the environment. The extent of that change in Geneva over the past century is clear when looking at the 1904 map.

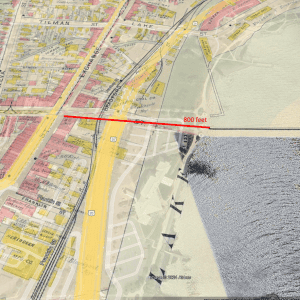

By overlaying the 1904 map on a Google Earth image you can get an idea of the increased distance from Exchange Street to the water.

First, the lakefront is more extensive than it was in the early 1800s. In 1796, Exchange Street was 148 feet from the water. Today, depending on where you measure, it is about 850 to 950 feet from the shore. Over time, government and landowners built almost everything south of Lake Street and west of the railroad tracks on fill. On Exchange Street, property owners built docks and wharves out to deep water to load and unload barges. The Syracuse, Geneva and Corning (Fallbrook) Railroad added fill for its tracks. The state added fill to extend the canal towpath to Long Pier. The city dumped excavated material on the lakefront when paving the city streets in the early 1900s. City officials encouraged the public to fill areas of standing water with their garbage. Finally, the state built the arterial in the early 1950s on a million tons of fill.

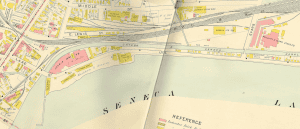

Second, except for a couple of private boathouses behind South Main Street homes (including behind the Prouty-Chew House), there is no sign of recreation facilities on Geneva’s lakefront in 1904. Today, the lake shore from the Community Playground to Geneva Lakefront Park is used almost entirely for recreation. This land use continues through Seneca Lake State Park to the current canal outlet. In 1825, the state extended the Cayuga Seneca Canal, which now enters the lake at the original Seneca River Outlet, around the north end of the lake. Packet boats then came directly into the harbor at Geneva. The importance of canal traffic led the railroads to the same spot fifteen years later, allowing transfers between canal and rail.

Geneva’s lakefront was crowded with factories and heavy industry reliant on proximity to the canal and rail connections.

Industry grew up close to these transportation connections. The map shows a soap works, wallpaper factory, several boiler manufacturers, a steam bending works, coal sheds, a machine shop, a boat factory, the gas works, lumber yards, freight stations, an ice company, and two stove works on the lakefront. These industries contributed to Geneva’s growth and prosperity, but the consequences of the industrial past include pollution and environmental degradation, which we are still a problem today. Commerce and industry remained the primary use of the lakeshore until the 20th-century. Then, the shift to automobile transportation and the decline in Geneva industries changed community priorities.

An 1877 photo from the Medical College on South Main Street shows the Fallbrook trestle crossing the water.

The earliest concern about lake access came in the 1870s with the construction of the Syracuse, Geneva and Corning (Fallbrook) railroad along the western shore of Seneca Lake. The line was built to bring coal from Pennsylvania to the rail and canal connections in Geneva. Property owners on South Main Street objected to the tracks blocking their lake access. They supported the development but didn’t want it on their property. As a compromise, the company ran the line on a trestle over the water from Mile Point. They moved all the residents’ boathouses, docks and sewers across the trestle. However, there were soon complaints about the danger of standing water on the west side of the trestle tracks. So, a decade after its construction, the company removed the trestle and put the tracks on fill along the shore to resolve this problem.

In the next decade, the state began the Barge Canal construction. It closed off the section of canal on the north side of Seneca Lake, opening and enlarging the original outlet on the eastern shore. Geneva’s harbor, lighthouse, and piers had fallen into disrepair by this time. Complaints increased about stagnant water and the unsightly lakeshore.

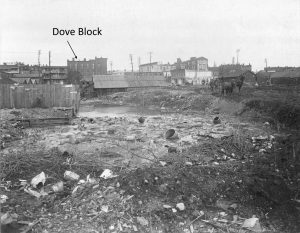

The area of standing water between the canal towpath and railroad tracks was a dumping ground for the city in the early 1900s.

In the post-Civil War period, Americans began to realize what they were losing in the nonstop drive to develop land and exploit natural resources. Frederick Law Olmstead created Central Park in 1857. Other large cities followed suit. National parks were started in these years. In Geneva, where industrial growth came later than in major cities, people began to discuss a lakeside park in the 1890s. A challenge to the project were the rail lines and canal towpath that blocked access to the lake. To create a park, the city would also have to buy land that was privately owned. At the time, Geneva was in the midst of paving its streets, and most residents saw a park as an unaffordable luxury.

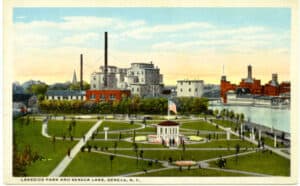

A postcard of Lakeside Park looking from Herendeen Manufacturing north to Patent Cereals and Nestor Malt House at the canal harbor.

In 1904, the city tried to acquire the land between Castle and Franklin Streets that lay between the shore and the Fallbrook tracks for a park. Several landowners were reluctant to sell, and the case ended up in court for more than a decade before the city secured the land. Finally, Lakeside Park opened in 1916, sandwiched between Herendeen Manufacturing and Patent Cereals. It was the first lakeside space devoted to public use and recreation. It remained in use for forty years before the state turned it into a parking lot during the reconstruction of 5&20. After this, public recreation activities on the lake were concentrated at the State Park until the arterial was re-routed in 1989 and the current city land first developed as Geneva Lakefront Park.

The arterial construction replaced the park and dilapidated factories with asphalt and large grassy medians. It cut the city off from the water that had allowed its growth.

When we visited the waterfront, it was interesting to note what the children noticed. Many were shocked at the lack of care Genevans had for the lake and the environment in the past. Some focused on the presence of trash and didn’t understand why people would treat Geneva’s lakefront so poorly. I tried to explain that people had different priorities then and that they didn’t understand the consequences of choices that made sense to them at the time. Nonetheless, the students and I all preferred today’s lakeshore to that depicted in our photos of the past.

Note on Sources

In addition to looking at the 1904 Atlas and Geneva newspapers, I relied heavily on the 1989 book Geneva’s Changing Waterfront, 1779-1989 by Kathryn Grover. It was written to accompany the Historic Geneva exhibit of the same name and extensively documents the changes on the waterfront over Geneva’s history. It was written just prior to the relocation of the arterial and the lakefront hotel construction. It is unfortunately out of print, although there are a couple used copies available online and there is a copy in our library and the Geneva Public Library.