Railroad Accidents and Safety

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

In December 2019, I wrote a post on fire and steamboat disasters. A driver had recently totaled my car outside the museum. This was my second of three car accidents that year, so disasters were on my mind. I recall saying several times at the end of 2019 that 2020 HAD to be a better year. Well, we all know how that went.

I ended that post with the promise to continue with railway disasters in the new year. Experiencing a global pandemic suppressed my interest in looking back at the terrible past for a long time. Despite the continuing sorry state of the world, I recently thought about returning to the topic. Defying belief, in September my car was again totaled while parked on South Main Street (now you know why there is plenty of parking near the museum). I am beginning to think someone has it out for me…or my cars. I decided it was a sign that I should return to the topic of accidents, which dovetails with our theme on death and mourning this fall.

As anyone learned who attended one of our fall programs, death was ever-present for Americans in the 19th century. With no understanding of germs or effective treatments for infections, epidemic disease was frequent. Bacterial infection and hemorrhaging killed many women in childbirth, and stillbirths were common. Over the century, one half to one third of children died before their fifth birthday. Some families were fortunate and had few losses, while losses devastated other families. Even the well-to-do Swans only had two of their six children outlive them.

Disease and accidents disabled and disfigured many people in 19th-century communities. From smallpox scars to withered limbs to missing fingers or eyes, those who survived often had visible signs of damage. The Civil War devastated a generation. Steam power and industrial machinery made production and transportation faster and more efficient, but it was decades before safety caught up with productivity.

Even today, agricultural work is difficult and can be dangerous. Livestock are always hazardous to work with. People were kicked by horses, gored by bulls, and thrown from runaway wagons. Scythes, sickles, and other tools could cause damage to limbs and digits. When farmers moved to using steam-powered equipment, the dangers increased with the speed of the machines. The same was true for factory work. Sharp hand tools could cause injuries, but those caused by steam-powered machinery were much worse and more likely to be deadly.

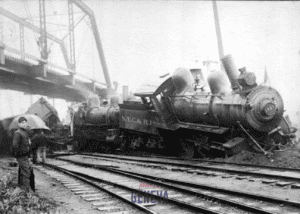

Rail transportation was particularly dangerous to workers, pedestrians, and passengers. The Geneva newspapers reported on rail disasters near and far, including collisions and derailments, with gruesome detail. Rail work was the second deadliest occupation after coal mining. New York Central employee Isaac Riley is buried in Washington Street cemetery. His monument was paid for by railroad president Erastus Corning. In 1851, Riley was crushed between two stopped rail cars at the Geneva station. A second train came down the track, colliding with the one he was standing near. In 1873, two railroad workers died during a terrible storm when a bridge over Marsh Creek collapsed while their train was on it. Collapsing bridges, broken axles, collisions, and trains running off the tracks seem to have been common causes of fatal accidents in the 1800s. In several instances, passengers were burned to death when stoves or lamps set the cars on fire during a derailment. People were also injured by “snakeheads” or curved strap rail. Early tracks were wooden with a thin strap of iron laid along the top. The nails holding these straps down would wear out from the heavy trains. The loose strap could then get lifted by a wheel (like a striking snake) and rocket through the bottom of the train car, causing injury or even death. People throughout the country also died crossing railroad tracks because there were no safety gates at most crossings.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper detailed the “Angola Horror,” a railroad accident that cost 49 people their lives.

Manual operations on a fast moving and heavy train caused many train accidents. Rail workers had to couple and decouple the cars by hand. Workers assessed experience in the field by the number of missing fingers on their hands. Braking was also manual, which led to problems slowing the cars down for obstacles on the track, including stopped trains. At the engineer’s signal of an emergency, brakemen used hand controls to apply the brakes. Four or five men ran over the cars to get to each one’s brakes. This was a slow process and very dangerous for the workers, who sometimes fell off the cars or were killed by colliding with a bridge or other obstacle outside the car. Sometimes trains collided because they could not be stopped fast enough. Many of the worst disasters were due to this failure, including a terrible crash at Angola, New York in 1867.

One of the biggest challenges to greater safety was an early lack of concern about it. The newspapers reported a variety of awful things that happened to people, but usually with the sense that bad things just happened. Individuals might be blamed for poor choices, but little thought was given to whether the environment could be changed to make it safer for people. Life was risky, and Americans didn’t believe you could do much to make it less risky.

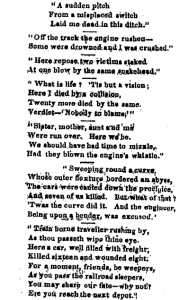

Evidence of this attitude is seen in a series of epitaphs originally published in the New York Times and reprinted in the Geneva Gazette in 1859. The writer suggested humorously that putting crosses with epitaphs at the sites of deadly accidents would remind “passengers of the peril of their situation and [be] a continual memento of the uncertainty of life on rail roads.”

By the beginning of the 20th century, thousands died each year in railway accidents. Attitudes about safety began to change as railway travel exploded after the Civil War and the death toll mounted. Among the first to think differently about safety were the engineers devoted to improving machinery. When an 1882 jury blamed a New York collision on the actions of the conductor, brakeman, and water boy, the editors of the magazine Mechanics—A Weekly Journal of Engineering and Mechanical Progress wrote:

“The intelligent observer cannot fail in his own mind to locate the blame with the general superintendent. The fault in this case is not with the employees, and other accidents will demonstrate that the brakemen and conductors on this road will be forced by the unwritten rules of the road to do things which, in case of accident, will in every instance throw the blame upon their own shoulders, unless juries take a more liberal and comprehensive view of the railroad rules, written and unwritten. It is notorious on The New York Central that brakemen [on stalled trains] do not go back to protect [oncoming] trains. In case of accident, the superintendent calmly points to his rules and says, ‘they ought to go back. If they do not, they are the blamable parties.’ It is not at all probable that on a railroad as carefully managed in many respects as this one is, these deviations from important rules are unknown and not connived at by the superintendent and his subordinates, and this being the case, he is certainly responsible for the violation of his servants.”

Innovators developed technical improvements that could save lives. Manual couplers were replaced with automatic ones that didn’t need a worker between the cars. A major improvement in safety came with George Westinghouse’s invention of the air brake in 1869. It instantaneously applied the brakes from the engine car and more effectively slowed the train. Horrible accidents continued despite these inventions. Outfitting all the cars on a railroad was expensive and often companies were reluctant to spend the money required. There was no standardization of cars and only varied state regulations for equipment. There were no requirements that railroads adopt these changes nationwide.

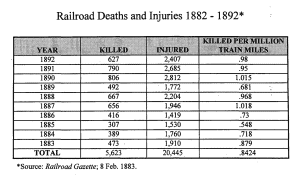

People became appalled at the regular loss of life in railroad accidents. Railroad unions and the public began to agitate for regulation of railroads in the 1870s. In 1893, Congress passed the Safety Appliance Act. It required power driving wheel brakes on engines and most of the cars, automatic couplers on all cars, sufficient handholds on the cars, and that the Interstate Commerce Commission would have the power to set and enforce standards for car coupling. The government began to collect data on safety and accidents in the early 1900s to guide regulations. Gradually railroad companies recognized that safety was an investment and good for profits as well as passengers and workers. Companies began to train employees in safe procedures. Safety culture became a part of railroad culture. At 995, deaths and injuries for 2023 are at their highest since 2007, but pale in comparison to the rough guess of 3,034 in 1893.

The work of safety improvement continues today as our expectations around it are raised. With railroads carrying heavier, faster, and more hazardous loads, Congress continues to revise safety requirements, most recently with the Railroad Safety Act of 2023, following the East Palestine derailment in 2022.

Sources

Adams, Charles Francis Jr. Notes on Railroad Accidents. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1879.

Crawford, Jason. “‘Someone Has to Get Hurt, Occasionally.’ How Factories Were Made Safe.” September 2021. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

McDonald, Charles. “The Federal Railroad Safety Program: 100 Years of Safer Railroads. U.S. Department of Transportation,” August 1993.

National Safety Council. “Railroad Deaths and Injuries.” Retrieved November 1, 2024.

If you’re into model railroading near me, Northlandz is a must-visit. The layouts and exhibits truly bring model trains to life in an inspiring way.