Home » Blog » The Evolution of Museums and the Geneva Historical Society

The Evolution of Museums and the Geneva Historical Society

September 18th, 2014

By John Marks, Curator of Collections and Exhibits

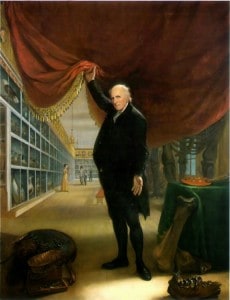

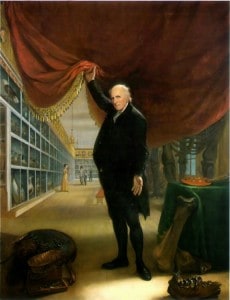

Charles Willson Peale is considered the father of American museums. (A painting by his son Rembrandt hangs in the main hallway of Rose Hill.) In 1786 he opened a museum of natural history in Philadelphia, which included an extensive portrait gallery; Peale justified this by saying man was at the top of the natural order. He charged 25 cents and felt that he offered “rational amusement,” what we might call leisure time education.

|

| The Artist in His Museum (self portrait, 1822) |

Peale pioneered elements still found in today’s museums. He presented “blockbuster” attractions such as a mastodon skeleton excavated in Ulster County, New York. He offered hands-on activities and evening lectures, and in 1816 provided gaslight for the comfort of his visitors. He also experienced challenges that are still with us. His museum struggled to maintain financial support, and did not have a good succession plan for survival after Peale’s death.

While Peale’s museum was almost immediately popular, the Geneva Historical Society had a longer, slower arc. Formed in 1883, membership was restricted to white males over 45 years old who had been born in Geneva. The mere announcement, by Rev. Dr. Hogarth, of an organizational meeting sparked an editorial in the Geneva Gazette of May 18, 1883:

“It would seem feasible to extend the membership so as to embrace all who have resided in Geneva 45 years or longer…it would appear that in an organization of this kind it is desirable to enjoy the fraternity of the older settlers, as all would become deeply interested in reminiscences to the very oldest period attainable. The editor of this paper is ‘barred out’ under the call, tho’ his residence in Geneva dates from 1823 – extending over a period of about 60 years. Open the doors, Dr. Hogarth!”

The main activity was reminiscing about people and events within the members’ memory. Until the 1940s, the historical society went through a cycle of a few years of activity followed by numerous years of dormancy. In 1941, the group had its first space at 501 South Main Street and began collecting and displaying artifacts. In 1946, the historical society was forced to move to vacant classrooms in the old Junior High School until 1950, then went to Lewis Street School for the next ten years. In 1960, Beverly Chew gave his home at 543 South Main Street, which remains the historical society’s headquarters.

Collection and display of artifacts was haphazard in the early years. Objects were often accepted for the following reasons: “it’s old”; “it’s very nice”; “my great-uncle brought it back from his trip to _____ in _____.” As collections outgrew the historical society’s space, things were put everywhere with few labels. Visitors loved it, and many think of that time as the good old days.

The pattern continued when the historical society moved into 543 South Main Street, only with more room to spread out. Objects were displayed for their own sake and there were few records kept about them. The donor’s name might be written down, but little other information as everyone at the historical society knew the donor and his or her story.

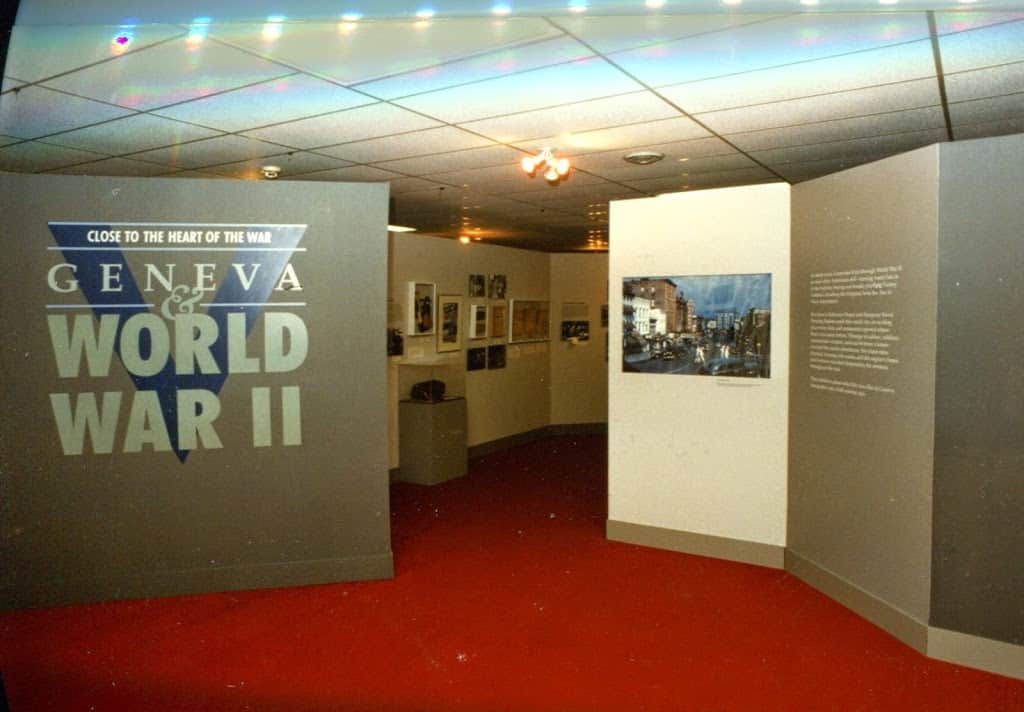

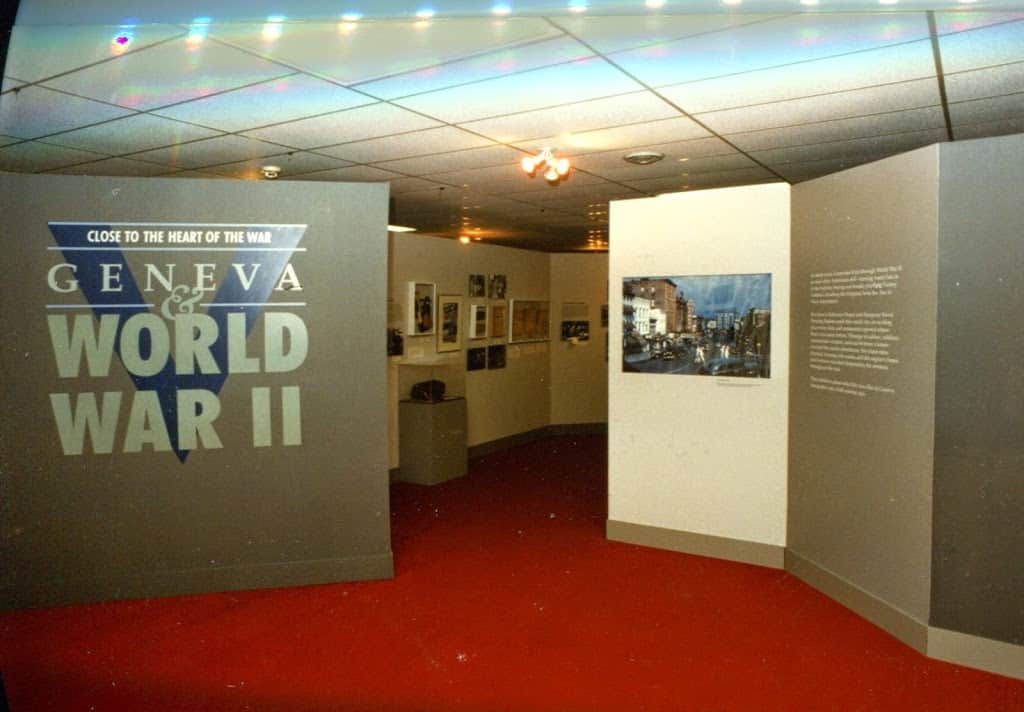

Change began in the 1980s, the golden age of New York State grant money. The staff identified important topics in Geneva history that hadn’t been exhibited, and for which we had little information and artifacts. These exhibits included African Americans in Geneva, the waterfront, the nursery industry, and the local impact of World War II. Outside researchers were hired to do oral history interviews, collect photos and artifacts, and write and design the exhibits. The historical society published books from these projects which are still in circulation.

Today we focus our collecting and exhibiting on areas most relevant to Geneva’s history. We look for provenance, or a Geneva-related story, when accepting artifacts; we create exhibits that connect to the city as we know it now. (Some connections, such as the War of 1812, are harder to sell than others.) We also move outside our building and reach out to audiences where they are, rather than wait for them to find us. While we don’t have a mastodon and use LED lights rather than gas, we’re still following many of Charles Willson Peale’s ideas.