An Officer and an Artist

By Alice Askins, Site Manager for Rose Hill Mansion

|

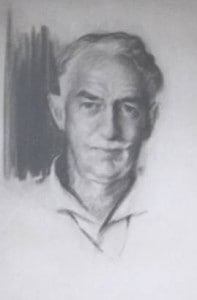

| Waldo Hutchins |

J. George Stacey Jr. painted the portraits of Waldo Hutchins and Margaret Hutchins that currently hang in the Music Room at Rose Hill. When I looked for more information about George Stacey, I found that he was a versatile and busy man.

Born in 1863 on the family farm in Fayette, east of Rose Hill, George spent his adult life in Geneva. As a boy he showed artistic talent and the Historical Society owns one of his boyhood sketchbooks. Though George had an eye for the details of everyday life, his favorite subjects were weapons and fighting. In 1881, the Geneva Advertiser reported that “Mr. J. George Stacey of Genevawill attend the State shoot in June, being one of the best shots in the Seneca Gun Club of Waterloo.” The previous year he had enlisted in the Folger Corps, a militia unit that became part of the NY National Guard in 1880. By 1887, he was Quartermaster of the 34th Separate Company, which had evolved from the Folger Corps.

George graduated from Hobart Collegein 1886. Four years later the Advertiser ran a notice that Charles Burrall had taken J. George Stacey Jr. as his partner in E. J. Burrall & Son Insurance. (The Stacey and Burrall families were related.) One can picture George in the ‘90s, working with his cousin and spending a lot of time at the armory moving up the ranks. In May 1898, the 34th was mustered into the army for the Spanish-American War, and among the officers was Captain J. George Stacey Jr. The 34th went to Camp Algerin Virginia, but never saw action. By August, George had typhoid fever and was not expected to live. His fiancée, Bessie Langdon, rushed to his side for what everyone thought was a deathbed wedding. Fortunately, George pulled through; the newspapers found this “Romantic.”

Once home, George continued his work with the National Guard, but professional he seems to have switched from insurance to plumbing. In March of 1901 he put a notice in the Daily Times, announcing that he had dissolved his partnership with Dorchester and Rose, in a steam fitting and plumbing business and from now on, Stacey would do plumbing by himself. In August 1902, he bid $2,640 on the plumbing contract for the YMCA building. As it turned out, nobody got the contract – the YMCA decided they did not have the money for plumbing after all. In April of 1904, the Times reported that Stacey had won the contract for the installation of sewer and water connections in the Geneva streets that were to be paved that year. Shortly after, George took the Master Plumber exam. In 1905 he started running an ad in the Times: “IF YOU ARE GOING TO BUILD THIS SPRING, ask J. George Stacey to bid on your Plumbing, Heating, and Ventilating. You will not only get a fair price, but also some valuable ideas.”

|

| Margaret Hutchins |

While building his plumbing business, George continued to be active in the community. He helped organize the yacht club in the late 1890s. When he attended the first meeting of the new Chamber of Commerce in 1902 – he was asked to speak, but refused because he was unprepared. Also in 1902, the Daily Times said he was the probable Republican nominee for President of the Common Council, though apparently he never took that office. For the rest of his life, he held such honorary appointments as Grand Marshal of the Military and Industrial Parade (July 4, 1910,) judge at the Fireman’s Parade (August 1914,) and one of the committee considering a new proposal for a veteran’s memorial in Pulteney Park (1937).

For several years Captain Stacey ran the 34th . He was not afraid to try new ideas. In 1901 he replaced the glaring arc lamps in the armory drill shed, with softer gas lamps, which he considered a qualified success. He thought about installing a swimming pool in the armory, and traveled to New York Cityto find out about options and costs. This plan seems not to have worked out. In 1902, George allowed a businessmen’s gym class to use the drill room on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday afternoons. The police also arranged to use the gym and shooting range at the armory.

The Times reported that Captain Stacey was President of delinquency court where members of the 34th had to answer for unexcused absences from parades and drills, and for being behind in their dues. In November of 1902, 60 guardsmen were summoned to the court; “Capt. Stacey. . .Was Lenient With the Militiamen.” The fines levied were nominal, and many of the excuses “ludicrous.” Sadly, the paper did not report the excuses in detail. The Times did note that one of the men called Stacey on the phone, “and pleaded guilty by wire.”

|

| Self-Portrait, ca. 1924 |

In 1904, George resigned from the Guard. With the demands of his business, he could not give the 34th Separate Company the time it required. His resignation must have been temporary, though – in 1913, The Syracuse Heraldannounced that Captain Stacey was retiring after 26 years of service. He believed a younger person should take up the burden of Captain of the company. At this point he received the brevet (temporary) rank of Major. During World War I George trained the high school cadets from Geneva, Waterloo, Seneca Falls, Phelps, and Ovid. For this work, he received the full rank of Major, though he preferred to be called Captain.

It is safe to assume that while he was in the middle of two careers, plus fatherhood and public service, George had little time for art. Warren Hunting Smith tells us, in Gentle Enthusiasts, that George returned to it increasingly in his 50s. Mrs. Stacey and her sister had inherited a Gothic Revival house on Jay Street, and George had a studio in the barn. His works were exhibited and sold locally, and sometimes received commissions for portraits. (Smith says that his portraits of men were commissioned, but his portraits of women were for fun.) He studied at the Art Students’ League in New York, and spent a summer at an art colony at Provincetown in the 1920s. Though best known for his portraits, George also produced a few still lifes. In 1927 one of his still lifes, a study of Japanese vases and oriental rugs, won a prize in an art show in Rochester in 1927. Hallett Burrall Jr. remembered his cousin George paying him ten cents an hour in 1932 to sit for his portrait. Hallett could not sit still for more than an hour, so the portrait took most of the summer to finish. Warren Hunting Smith tells us that a visiting architect thought Stacey painted with much of John Singer Sergeant’s bravura – a compliment that may have pleased Stacey more because of the military echoes of the name.

|

| Landscape |

Wonderful information for ancestry research..