Geneva’s Changing Waterfront

John Marks, Curator of Collections and Exhibits

Geneva’s Changing Waterfront was the name of a 1989 exhibit and catalogue by researcher Kathryn Grover. The title sounds “ripped from the headlines,” as some TV shows say. Seneca Lake and its shore have always been valuable commodities to Geneva but the nature of that value is always changing.

The lake offered food and transportation for Native Americans. They had no known towns on the lake – those were situated on hilltops for defensive reasons – but in the summer people camped on the shore to catch and dry fish. This was especially true in the shallow areas near inlets and outlets where it was easier to wade out and use nets. A canoe could travel up the Seneca River and east almost to the Mohawk River; after a short carry, it could continue out to the Hudson River.

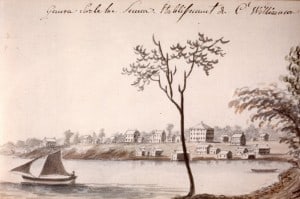

American settlers valued the bluff that became for its view and healthy air. Land around the foot of the lake (the Finger Lakes flow south to north, so the north is the “foot”) was swampy and people who lived near it contracted “Genesee fever,” probably a form of malaria. Land agent Charles Williamson laid out the new village on the high ground; today’s Pulteney Park was the central business district, with homes down and nearby. The bottom land was occupied by warehouses and less-affluent citizens.

The lake was a major transportation route from the 1790s until the early 20th century. Lake schooners and steamboats carried produce and goods from around the lake to Geneva, which became an inland port when the Erie Canal was completed in 1825. (The Seneca-Cayuga Canal was in operation prior to 1825.) Steamers hauled “gangs” of barges on the lake between the Seneca-Cayuga in the north and the Chemung Canal in the south.

Commerce has always located near the best transportation routes. Factories and warehouses built docks along the downtown lakefront. Hotels, taverns, billiard rooms, and bordellos on Exchange Street served the lake and canal traffic. Until the 20th century, respectable businesses were located on upper Seneca and Castle Streets, away from the riff-raff.

In the 1950s, the lakefront was again valued as a transportation route, this time for a bypass around downtown. Almost a million tons of fill were used to expand the shoreline so Routes 5 & 20 could avoid local streets. Divided highways were laid out with a wide grassy median. The downtown lakefront had no perceived value until the 1980s when the roads were moved to the west, creating room for development.

This is a simplified history of the waterfront. A more complicated version includes a century-long debate about how to use the lakeshore closest to downtown. From 1916 to the 1950s, Lakeside Park, at the end of Castle Street, was a pleasant recreational site but it took eleven years of heated debate to be built. The Historical Society has blueprints, master plans, and recommendations for waterfront development dating back to 1935. They range from a mix of industry, retail, and recreation, to single-use options. New reports are added to our archives every few years.

This 1935 proposal for a park begins at Lake Street (far left). The eastern portion, not shown here, included ball fields and a marina, similar to what was finally built in the 1960s as Seneca Lake State Park.

I’ll refrain from giving an opinion on lakefront development; I’m one person, and this is a hot topic. I will say that the Historical Society is a great resource for anyone seeking the “long view” of the lakefront’s history. We have maps, photographs, postcards, and the aforementioned plans and studies. Geneva’s Changing Waterfront: 1779-1989 is out of print but used copies may be found in local stores and the Geneva Public Library should have a copy as well. (We are considering digitizing the book and offering on-demand copies in the future.)

I’m from Clyde and now live in California. My parents met at a dance hall in 1939 that I remember them saying was in Geneva near the north end of Seneca Lake – assuming along the road (5&20). Does anyone have any information about what it was called and where it was? Or does the building still exist?

Carole Gibson

Bet it was club 86. Building still exists and business is still running.

I found a map of Factories were always portrayed with smoking stacks;; no smoke meant no work. Looks like it was drawn by Augustus Koch. It’s says 57 of 100.