Classical Music in Geneva, Part II

By John Marks, Curator of Collections and Exhibits

The standard museum research model is that research is completed, an exhibit is created and opened, and programs may be tacked on afterwards. Music in the Key of Geneva is open-ended. There are so many possibilities and research to uncover that what we produce is subject to change at any time.

This blog is a case in point. I thought I would address classical music chronologically but I continue to find interesting stories from several time periods. I’m not one to let orthodoxy stand in the way of a good story.

Patrick S. Gilmore

Anyone who’s watched The Music Man has heard a reference to “Gilmore” in the prelude to “Seventy-Six Trombones.” He was Patrick S. Gilmore (1829 – 1892), an Irish-American immigrant and musical innovator. He was the first to arrange horns against reeds which became the basis for all big band orchestras (I noticed this on Lawrence Welk last Saturday night). He began promenade concerts in Boston and ringing in New Year’s in Times Square, and he brought contemporary European classical music to the American masses. Gilmore came to Geneva in April 1892, about five months before his death.

Victor Herbert

The band continued after Gilmore’s death under the direction of Victor Herbert. He brought the band to the Smith Opera House in November 1896. Herbert became famous in his own right as a conductor and composer of operettas including Babes in Toyland. As musical tastes changed he began composing for the Zegfield Follies and other Broadway shows.

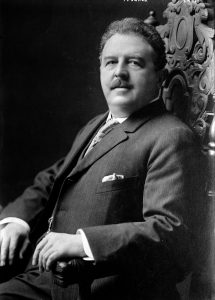

Conductor Emil Paur (1855 – 1932) was less of a household name. He worked in the United States from 1893 to 1910, conducting in Boston, New York, and Pittsburgh. While I haven’t found any early recordings, he did record works on reproducing (player) piano rolls, another way of bringing professional-grade music into the home.

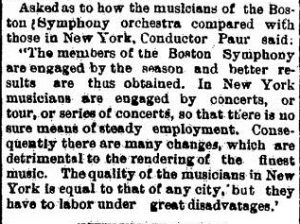

In April 1899 Paur was based in New York and touring with his own orchestra when he came to town. The Geneva Daily Times featured an interview as well as a concert review. The formation of 19th century orchestras was different from today, as Paur explained:

The review began, “Geneva’s reputation as a musical city suffered grievous injury last night, for there was a pitifully small audience to hear what was undoubtedly the best concert ever given in Geneva.” Concert presenters continue to struggle with this problem. They may or may not be comforted that it has always been thus.

The Andrews Family Opera Company, 1893

Summer attendance was a particular problem for the Smith Opera House. In 1899 Mr. Hardison, the Smith manager, kept the theater dark as “Genevans, it appears, do not want summer amusement of any kind, or at any cost.” The previous summer the Andrews Family Opera Company from Minnesota “sang high-class operas exclusively, and sang them well” but commercially “proved a flat failure.”

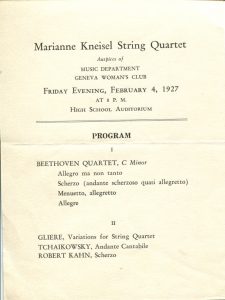

The Music Department of the Geneva Woman’s Club brought classical performers to the city, often guaranteeing money to ensure that concerts would happen. The Kneisel String Quartet was the leading chamber music group in the United States from 1885 to 1917 when leader Franz Kneisel decided to devote his time to teaching. Later his daughter Marianne started her own quartet and played the high school auditorium in February 1927.

The Music Department of the Geneva Woman’s Club brought classical performers to the city, often guaranteeing money to ensure that concerts would happen. The Kneisel String Quartet was the leading chamber music group in the United States from 1885 to 1917 when leader Franz Kneisel decided to devote his time to teaching. Later his daughter Marianne started her own quartet and played the high school auditorium in February 1927.

In 1952 Marianne revived the Kneisel Hall Chamber Music School in Blue Hill, Maine. Among other programs there is a seven-week learning and performing residency for young musicians. Genevan Hannah Collins (left, with cello) is an alumna of the program, a professional musician, and a visiting assistant professor at the University of Kansas. She is the co-director of Kneisel Hall Blue Hill: Together in Music that puts teaching artists into the school and performs in the community. She does similar work here during the annual Geneva Music Festival, which I will write more about in the future.

In 1952 Marianne revived the Kneisel Hall Chamber Music School in Blue Hill, Maine. Among other programs there is a seven-week learning and performing residency for young musicians. Genevan Hannah Collins (left, with cello) is an alumna of the program, a professional musician, and a visiting assistant professor at the University of Kansas. She is the co-director of Kneisel Hall Blue Hill: Together in Music that puts teaching artists into the school and performs in the community. She does similar work here during the annual Geneva Music Festival, which I will write more about in the future.