1968: A Year of Change

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education

In 1967, Hobart and Williams Smith students protest restrictions on students like curfews and house rules.

As many of our readers might recall, 1968, the year Rose Hill opened to the public, was an historic year. Looking back, it was a watershed moment when Americans began to reckon with the postwar world they had built. Reading through that summer’s issues of the Geneva Daily Times you get a real sense of the changes afoot in the world.

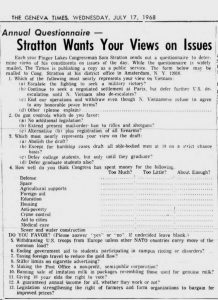

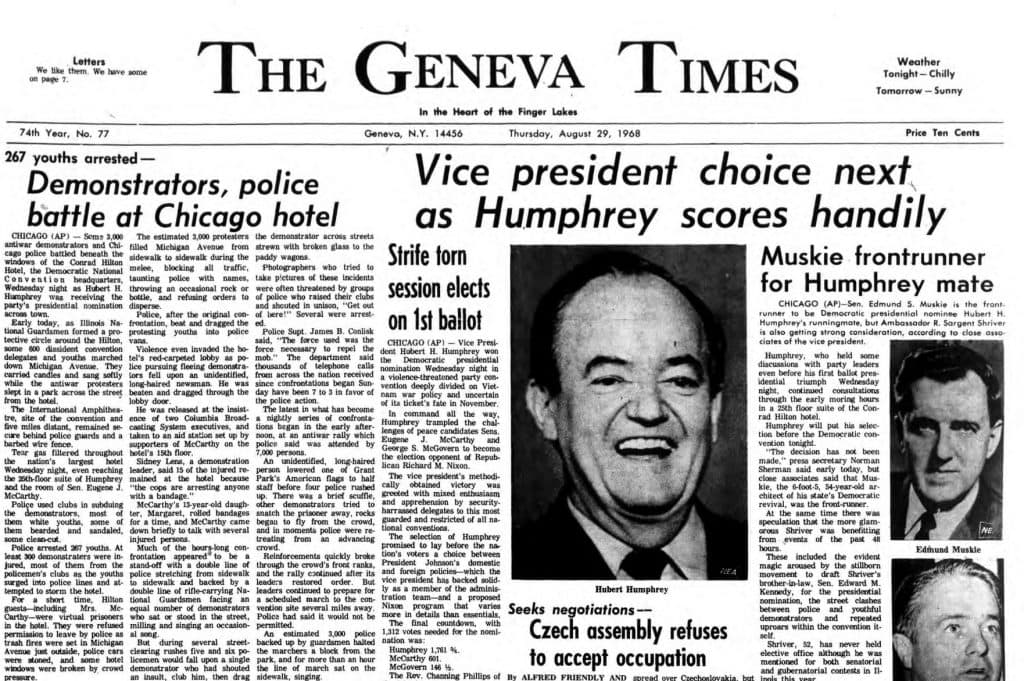

For those who don’t remember what local newspapers were like before the Internet, at least half of the Geneva Times was devoted to national and international news in 1968. As it was a Presidential election year, a great deal of space and opinion that summer was dedicated to those running for the office and to the party conventions. The conventions were less showy than today, with one Broadway producer declaring the Republican convention a flop: “It’s a terrible bore. Too long. Too dull. There’s a mortician’s conference in town, and it’s more lively.” He likely didn’t say the same about the Chicago Democratic convention a month later, in which turmoil over the Vietnam War roiled the delegates inside the convention. Outside, Chicago police beat up student protesters and journalists alike. All of it was broadcast live on TV.

Reports of violence along with the Democratic delegates’ final choice appeared on the front page of the Geneva Times.

The violence at the convention was the culmination of a long year of violence and validated some people’s fears that the world was falling apart. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy had been assassinated; unrest and upheaval had seized college campuses; there had been race riots and armed battles between police and activists. That summer and early fall, the newspaper covered the worsening war in Vietnam, revolution in Czechoslovakia, civil war in Nigeria, bombings in Germany, and student protests in Brazil, France, and the United States.

In response to the assassinations and the growing violence in urban areas, federal gun legislation was under debate in congress. 71% of Americans polled favored federal gun control, including registration. The first federal gun control law was passed in the fall, which blocked mail order sales of rifles and shotguns and prohibited gun purchases by most felons, drug users, and people found mentally incompetent.

1968 was also the year the full provisions of the Immigration Act of 1965 went into effect, abolishing the quota system established in 1921, which favored immigrants from Western Europe and severely restricted those from Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa and Latin America. The new law also prioritized relatives of current immigrants and trained professionals.

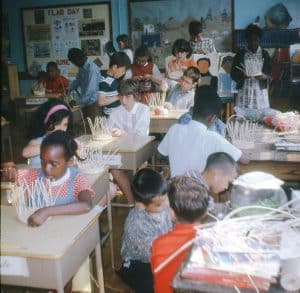

Like other communities Geneva was wrestling with change. Concern about racial segregation in the city prompted efforts to expand affordable housing. The school board was attempting to combat school segregation by converting two neighborhood elementary schools (the old North Street School and Prospect Street School) into K-3 and 4-6 schools. Both efforts brought about angry meetings and discussion about the consequences of change.

The newspaper was full of the tension between age and youth, and it was not confined to Berkeley. Hobart and William Smith Colleges President Albert Holland resigned that summer after disagreements with the HWS Board of Trustees about the pace and types of change to be embraced at the schools. Holland painted the dispute as a conflict between a president who wanted change with the times and a conservative board that didn’t. As at other institutions of higher learning, students at HWS were looking for greater control over their college experience, particularly their “non-academic life.”

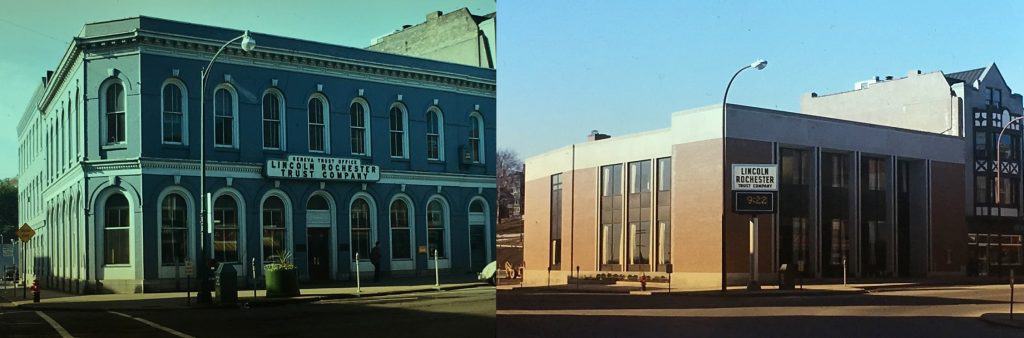

The preservation of Rose Hill is also part of this history of change—or rather of the reaction against it. As change accelerated throughout the 1960s, more people began to notice that something was being lost as the country’s rapid post-war growth displaced old and elegant buildings for the modernist architecture of Marcel Breuer and I.M. Pei. or the superhighways of urban renewal. Most galvanizing was the destruction of New York’s Penn Station in 1964, which prompted the creation of the National Historic Preservation Act and countless efforts to preserve historic buildings.

The face of Geneva was also remade by Urban Renewal efforts and modern development. At the same time that Rose Hill was being restored, and the Geneva Historical Society was working to preserve houses on South Main Street, the National Bank of Geneva demolished its 19th-century building in favor of the one that today sits on Seneca and Exchange Street (now Five Star Bank). Geneva Savings Bank and Lincoln Rochester Trust Company had already knocked down their 19th-century buildings on Seneca Street in favor of modern office buildings. The banks wanted to redevelop in anticipation of the modern shopping area that the city’s Urban Renewal program was planning. Ironically, the Urban Renewal parcels were never developed, and in 1968 the original plan for them fell apart. Still, the banks had all stepped into modernity.

Looking back at 1968, what is most striking is how we are still arguing about a lot of the same things—guns, racism, drugs, freedom, military action. It is easy to see some significant improvements—the reduction in reported auto accident deaths is noticeable—but can be sobering to realize how much has not changed.

Join us on July 21 from 12 to 4 p.m. for Rose Hill Through the Ages and celebrate 50 years of a good change, the preservation of Rose Hill Mansion. Rose Hill Through the Ages will feature presentations about the restoration of the house and the interpretation of its history. Find out how the Sullivan-Clinton Campaign impacted the property, explore the changing ideas about what historic house museums should be, and learn about the many families that lived in the house after the Swans. There will be games and hands-on activities for all ages. Lock 52 Jazz Band will perform from 2–4 p.m.