Disasters on Land and Water

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

This has been a difficult year for me and my car. We have been in three accidents, resulting in thousands of dollars in damage and one totaled car. Thankfully none of the accidents involved any injuries—the worst one occurred when my empty car was parked on South Main Street! To make myself feel better about the paperwork and expense, I decided to look back at the local newspapers to see what types of accidents were reported in the 19th century and how people dealt with them. It did make me thankful for modern safety standards and workplace protections.

Newspaper reports of accidents were less common in the first half of the century. This doesn’t mean they didn’t happen, but the village of Geneva was small. Presumably most local people knew everyone’s business, good and bad. Editors of the weekly newspaper relied heavily on reports from other newspapers for content. They devoted most of their space to politics, ads, and disasters in larger cities. Fire, flood, explosions and sinking ships were the most commonly reported.

During the early 1800s, fire and maritime disasters were reported most often. Newspapers printed village bylaws governing fire regulations and citizens’ responsibilities for preventing and fighting fires. Fire insurance companies advertised frequently in the newspapers after the 1820s, but most homeowners and many businesses were uninsured. Fire insurance often did not cover all losses. Early companies only operated locally or state-wide and charged too little in premiums to cover losses when fires burned large areas of a city. 23 of 26 New York City firms were bankrupted following a massive fire there in 1835. After this, companies diversified their risks by insuring in multiple markets. In 1849, New York State was the first to require insurance companies to hold a minimum of $100,000 in capital. Companies like Aetna and New Hartford began advertising their services in Geneva’s newspapers at this time.

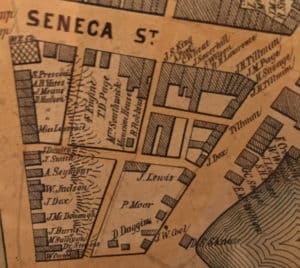

The south side of Seneca Street burned in 1856. This map of the same year shows the buildings that burned and their owners’ names.

By the 1850s, local fires were mentioned in the newspapers more often. A block of Seneca Street burned in 1856. The Geneva Courier listed all the owners and occupants of the buildings, along with their losses and insurance. The losses were calculated at $16,700, but insurance only covered $6,150 of these.

Steamboat accidents were also reported regularly, sometimes on Seneca Lake, other times reports detailed accidents on the Mississippi, the Great Lakes, or on ocean-going vessels. In 1844, the steamer Watkins had a propeller accident that killed two people on Seneca Lake. Shortly after it returned to service, two bolt heads from the boiler blew out, killing the fireman and injuring another. The Ben Loder, a steamboat designed to ferry 1,500 railroad passengers from Watkins Glen to Geneva, was converted to a towboat in 1853. In 1861, one of its boilers exploded, killing the assistant engineer and a deck hand. Others, including a dozen canal horses, were scalded. No one was considered to be at fault. The companies sustained losses, but nothing is said about compensation for the men killed.

Fire on a vessel is extremely dangerous, even today. In the 1800s, it could be the most deadly accident. Getting off of a ship is tricky at the best of times. In an era before strict safety procedures and crew training, there was little chance of an orderly disembarkation in a fire. The steamboat Erie caught fire shortly after leaving Buffalo for Chicago in August 1841. Despite the presence of a few small lifeboats on board, panicked passengers swamped them and they overturned. Most of these people drowned or fell under the steamboat’s wheel (which was still turning). The few who survived clung to the keel of the overturned lifeboat. One African-American man on board saved himself by trying to swim to shore, ultimately making it to an overturned boat. He was forced to trust to his strength when seeing “so many white people about [the boats] that I concluded there would be no chance for me… and determined to seek for my own preservation in some other manner.” Only one woman on the ship survived because she had a life preserver. Life preservers had been in a room blocked by the fire, so no one else had one. One of the young men who died on the Erie was David S. Sloane of Geneva, a member of the Y.M.C.A. The disaster was covered in the Geneva paper and was one of many included in an 1846 book by S.A. Howland, Steamboat Disasters and Railway Accidents in the United States.

Most of the disasters profiled in Howland’s book occurred between 1836 and 1841. 66 were steamboat fires, explosions, and wrecks; 30 were ships lost in coastal waters; and only were 12 railway accidents. 1841 was the year rail service began in Geneva. Train derailments, collisions, and boiler explosions soon overtook steamboat accidents, as rail service spread across the country. Next time we will look at rail disasters.

Sources

Dalit Baranoff, “Fire Insurance in the United States.” Found online 12/20/2019.

S.A. Howland, Steamboat Disasters and Railway Accidents in the United States. Second edition. Worcester, MA: Warren Lazell, 1846.

Very informative article. Sorry to hear of your personal accidents but glad you are okay.

Anne, this was good. One thing leads to another, as the saying goes.

Trying to make lemonade, as they say!