Medical Women’s Success

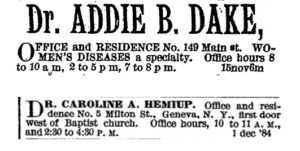

A photo of Dr. Addie Crowley Dake, one of the few women to practice in Geneva in the 1800s. Perhaps taken upon her graduation from Cleveland Homeopathic Medical College.

This past February marked the 200th anniversary of the birth of Elizabeth Blackwell, a pioneering medical woman. An 1849 graduate of Geneva Medical College, she was the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States. Blackwell’s foray into medicine came decades before women attempted to break into the ranks of architects, lawyers, engineers or other professions. Many ambitious American women followed Blackwell’s example, advocating for admission to medical schools and starting their own schools and hospitals to provide more opportunities for women. In 1880, 2000 women were practicing medicine professionally. By 1900, that figure more than tripled to 7,387. At 5% of doctors, there were more medical women than women in any other profession.

What made medicine so appealing to 19th-century women, and what made it possible for them to succeed in it? Their success was due partly to the low status of the medical profession in the mid-1800s and the lack of restrictions over who entered it. 19th-century medical women also benefited from changing ideas about women’s role in society. They crafted a path of entry into medicine by arguing that as the naturally sympathetic gender, they were ideally suited to caring for the sick and improving people’s health.

The 1800s were a period of enormous change in the United States. In 100 years, the nation went from a population of 5 million mostly white, rural, English-speaking people in 16 states, to 76 million people in 45 states. In 1900, 14% were born outside the U.S. and 39% lived in urban areas. New York City grew from 60,515 to 3,437,202 people, and the industrial output of the nation had soared. Old economic and social systems weakened and fell apart, and people sought new ways to organize themselves in new circumstances. Labor, once organized mostly by family unit, became divided. In the middle class ideal, women did the unpaid work of the household, and men left the home for a job with a paycheck.

A new ideology of gender roles emerged, placing women at the center of home life, while men acted in the public sphere. In a rapidly changing and uncertain world, a woman was to provide a refuge for her husband and nurturing environment for her children. Women were responsible for the morality of their family, and by extension the morality of democratic American society. A letter published in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal in response to Blackwell’s achievement summarizes this role and her departure from it:

Whatever may be the character and acquirements of this individual, it is much to be regretted that she has been induced to depart from the appropriate sphere of her own sex, and led to aspire to the honors and duties which by the order of nature and the common consent of the world devolve alone upon men…. Hitherto an intuitive sense of propriety has induced all civilized nations to regard the professions of law, medicine and divinity as masculine duties…. Woman was obviously designed to move in another sphere, to discharge other duties—not less important, not less honorable, not less angelic, but more refined, more delicate. Within her own province she is all powerful. She is the pride and glory of the race—the sacred repository of all that is virtuous, graceful and lovely. But when she departs from this, she goes astray from her appropriate element, dishonors her sex, seeks laurels in forbidden paths, and perverts the laws of her Maker.

Educated, middle class women firmly believed in their role as virtuous protectors of home and family. Many worked to expand the definition of womanhood and thereby their power in society. It was a short step from asserting women’s responsibility for morality in the domestic sphere to charging them with reform in the public arena. Some devoted themselves to religion and reform causes like abolition, temperance, and suffrage. Others pushed the domain of female authority to include education, health and hygiene. Women like Blackwell used the ideology of separate spheres to claim their place in medicine. They viewed medicine as a tool to improve society. She and other advocates for women’s medical training argued woman’s natural qualities of morality, sympathy, virtue and tenderness were essential in a physician. Female physicians would link sympathy and science, resulting in healthier families and a healthier society.

When Blackwell decided to pursue medicine, the American medical profession barely resembled what it would become in a century. Medicine was unregulated in most of the states, and in a country devoted to individual freedom and opportunity, nearly anyone could declare themselves a physician. Various medical sects had emerged to treat the ill health that was rampant in a society with little understanding of the causes of disease. Homeopaths, Thomasonians, eclectics and other types of healers developed new theories of disease and milder, if ineffective, treatments for them. The popularity among regular physicians of harsh treatments, along with their frequent inability to cure the sick or alleviate pain, reinforced the public’s bad opinion of doctors. Dependent on tuition for income, most medical schools took all paying students, and many had students who could barely read and write. It was difficult to bar anyone from using the title of doctor, even a woman.

Open-minded male doctors took on women as students. Non-sectarian and western medical schools gradually admitted them. Early women doctors and their allies started female medical schools, both to educate women as physicians but also to instruct teachers and homemakers in health and hygiene. Women physicians often served women and children, keeping their medical practice in line with their ideas about women’s role (women are still over-represented in these specialties today). Lacking the funds, networks, and connections of men, many women took work in institutions like asylums, hospitals, dispensaries, schools, and sanitariums. Considered lower status positions, they nonetheless provided a steady income.

I’ve only found two instances of 19th-century women physicians in Geneva. Caroline Hemiup was a teacher at the Classical and Union School who went to Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1878. She advertised her services several times in 1884 and 1885, but was listed as a teacher again in the 1892 directory. The other instance I’ve found is Addie Crowley Dake. She is mentioned in George Conover’s History of Ontario County and listed in the city directories from 1889 to 1896. What little is known about her indicates she followed a path similar to many women doctors of her time. She graduated from Cleveland Homeopathic Medical College and specialized in diseases of women. The business may not have been very successful in such a small town, as she left for Syracuse in 1897 and no other women practiced in Geneva until decades later.

The problem for women doctors was that the emphasis on their sympathy for the patient became a liability as medicine professionalized and became scientific in the early 1900s. All states required a license to practice medicine by 1900. This usually meant a diploma from a reputable school and passing a medical licensing exam. Both requirements forced poor quality schools to reform their curriculum or close, including many schools that routinely admitted women. The reformed schools were less dependent on student tuition and more likely to restrict female attendance.

In the twentieth century, the physician held up as ideal was the medical man in the laboratory, pioneering in medical science. Bedside manner and sympathy were secondary. Educated young women pursued new careers in nursing, librarianship, and social work. While women were not excluded as a whole from the profession, their entry was restricted and the appeal of the profession seems to have diminished, keeping their numbers flat until mid century.

Other Reading

Judith Walzer Leavitt and Ronald L. Numbers, Sickness and Health in America: Readings in the History of Medicine and Public Health, 1985.

Regina Morantz-Sanchez, Sympathy and Science: Women Physicians in American Medicine, 1985, 2000.

Ellen S. More. Restoring the Balance: Women Physicians and the Profession of Medicine, 1850-1995, 1999.