The Battle of the Avenue B Railroad Crossing

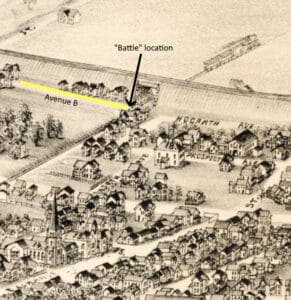

This slightly distorted 1893 birdseye view of Avenue B shows the area for the disputed railroad crossing at the New York Central Railroad tracks.

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

I was recently reading through Geneva’s online newspapers looking for references for an article and came across the Avenue B Street extension controversy of 1897. Looking at this relatively minor and seemingly inconsequential incident reveals a lot about the development of Geneva as a city and about the transformation of American communities in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

According to the Geneva Daily Times of December 31, 1897, the prior night there had been a “Big Village Row with the Central.” A later article would cite this and the lunch wagon controversy as the biggest disputes the village trustees had to deal with in 1897. It was also their last village action, as the city charter went into effect on January 1, 1898, and a new city council was seated in place of the village board the next day.

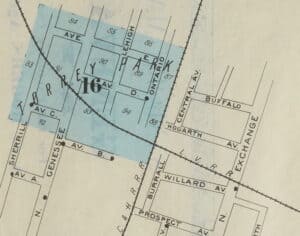

Development in the Torrey Park area around Avenue B had just begun at the start of the decade. Only about eight houses were on the street in 1897, but those residents had to travel down Genesee Street to North Street and over to Exchange to access the neighborhoods and businesses on the other side of the railroad tracks. I imagine pedestrians walked across the tracks at convenient points, but anyone with a wagon or carriage would have to follow the roadways. Crossing the tracks, then as now, was dangerous. Many roads and railroads had not been constructed with safety in mind, and there were no zoning laws or regulations regarding safety. What was convenient for a pedestrian or horse-drawn vehicle was not always considered when rail lines were laid and cut off access to parts of town.

In 1897 there were only 8 houses on Avenue B but they were isolated between the New York Central and Lehigh Valley Railroad tracks.

A petition was presented to the village board in September 1895, requesting that Avenue B be extended to Burrall Street and across the New York Central lines. Three trustees, Moore, Hawkins and Hoffman, were appointed to a committee to report on the cost of the extension. There was no mention of who put forth the petition, but the newspaper noted that it was “regarded as an improvement much desired.” A week later the paper reported the village attorney was looking into the extension.

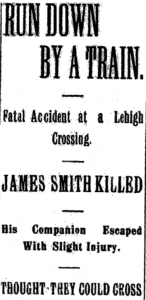

The newpaper had frequent reports of people killed crossing the railroad tracks, in Geneva and elsewhere.

In January 1896, the matter was shifted to the railroad committee, which was also after the NYCRR. They wanted the company to erect gates at level rail crossings to make them safer. Both committees had difficulty with the New York Central railroad officials, who did not want any more streets crossing the tracks at grade. Level crossings were a safety hazard to trains and the public, and the railroad was often held liable. People on or near the tracks were frequently killed. Sometimes the engine would derail in an accident. Before automatic barriers were developed, someone had to monitor the crossing and signal that a train was oncoming. Employing someone to do this for every level crossing was an ongoing expense for the railroad company. The alternative was to elevate one road above the other. Presumably the NYCRR wanted overhead bridges, which cost more initially but were safer. None of the articles indicate who would be responsible for the cost of constructing a barrier.

Over the course of the next two years, the main mentions of the issue in the newspaper are periodic requests from the committee for more time for the matter. Their final request was at a meeting on December 28, 1897, just days before the altercation. One editor speculated that the delay was to get the railroad staff off guard, for two nights later a work gang from the village assembled at the tracks in the dead of night and used boards and tile to construct a graded crossing over the tracks. After testing it with teams of horses, they headed out. At 6 o’clock a.m., a gang from the New York Central Railroad “came along, viewed the work of the [village] committee, and ruthlessly set to destroy it. They tore up the planks, dug up the tiles, pulled down everything that had been put up and blocked the way, stationing themselves along the route as men acting on guard.”

The village trustees met in the morning to discuss what to do next. One suggested calling the police and militia, another the hose companies. In the late morning, the railroad employees drove a caboose and several cars loaded with stone to the crossing and began dumping it alongside the track to prevent anyone going across it. Meanwhile, the trustees called a fire alarm and the Black Diamond, Hydrant, Nester, and Hook and Ladder companies responded, bringing their firehoses, connecting them and opening “fire:”

It was an exciting moment. Fully 1,000 people were upon the scene, and men laughed and women screamed. The railroad hands sought cover from the hissing and gurgling waters that threatened to wash away the cars, engine, caboose and all. In their rage, it is claimed, pins and other missiles, were thrown by some of the gang at the firemen, but the appearance of Chief Kane kept the men under restraint, who waited for the storm to pass, hiding in outbuildings and cars. The railroad men employed at the place and time were about forty in number.

The newspaper went on to report that the trustees removed the blockade and restored the crossing under guard from the fire companies.

Because he was expecting a passenger train to come through on the track, the railroad engineer moved the train, cars, and caboose back to the station. Once there, the trustees had him arrested on the charge of obstructing the highway. After the passenger train went through, the station workers returned with the caboose and their crowbars to block and dismantle the crossing, only to met with a torrent from the fire hose. As the newspaper put it, “The Central seems to be as determined to close the highway as the village is to have it open.”

Later that evening, a railroad official came to town with an injunction restraining the village from any further action on the crossing. This was followed by a lawsuit against the village. By the end of January, the matter was settled. The city agreed to pay the railroad’s court costs of $37.50. The injunction against the crossing was to remain in place. The city would have to negotiate with the railroad. The only further mention of the conflict was a lawsuit brought by one of the railroad workers against Village Trustee Hoffman for damages sustained in the altercation. I couldn’t find out how this was settled.

The issue of a railroad crossing continued to pop up in the meetings of the new Board of Public Works. They tried to get a crossing at Avenue E later in 1898, but that too was opposed by the railroad. The railroad’s decisions were backed by the New York State Railway Commission, which had the ultimate power over crossing decisions. The next location suggested was at Gates Avenue, which the city and the railroad agreed to in September 1900. The cost was estimated at $4000, and the city would fund the construction of the track elevation. The crossing was finally built and is still there.

Today, I imagine there is a long and bureaucratic process to request a new railroad crossing. It is hard to imagine a time when the trustees of a small village would take it upon themselves to construct one. These men were living when such decisions were moving out of the hands of local officials. A decision as local as crossing the street had to be negotiated among the local community, the railroad, and the state. In this and other matters, local interests had become intertwined with those of large companies and corporations. This type of negotiation would continue to evolve in the 20th century. The railroad industry was the first national business that required uniform regulations across local and even state lines. The industry’s power and importance led to a decades-long negotiation over the rights of the industry and the individual, changing transportation and commerce systems, local development and even the time. You could argue we are going through a similar transformation now with the digital revolution. So, the next time you walk or drive by one of Geneva’s abandoned elevated crossings, think about the work it took to put it there, and the ways in which the rail system changed our environment.