Building A Better Geneva: Urban Renewal, Part I

By John Marks, Curator of Collections and Exhibitions

For those of us of a certain age, urban renewal is the scapegoat for unpleasant change in our communities. “Why did they [always an unnamed “they”] tear down X, Y, and Z?” “Urban renewal.” While I sympathize with mourning the loss of what used to be, I wanted to find out what urban renewal really was, why communities embraced it, and who “they” were.

For those of us of a certain age, urban renewal is the scapegoat for unpleasant change in our communities. “Why did they [always an unnamed “they”] tear down X, Y, and Z?” “Urban renewal.” While I sympathize with mourning the loss of what used to be, I wanted to find out what urban renewal really was, why communities embraced it, and who “they” were.

Geneva felt urban renewal’s impact in the 1960s – 1966 to be precise – but the roots began in the 1950s. The decade began well enough. The Sampson military base was reopened for Air Force training during the Korean War, bringing back customers and prosperity that the city saw during World War II. Civilian and military support staff lived and shopped in Geneva, and the city was the closest destination for airmen with short leave from the base.

Geneva felt urban renewal’s impact in the 1960s – 1966 to be precise – but the roots began in the 1950s. The decade began well enough. The Sampson military base was reopened for Air Force training during the Korean War, bringing back customers and prosperity that the city saw during World War II. Civilian and military support staff lived and shopped in Geneva, and the city was the closest destination for airmen with short leave from the base.

In December 1953 Mohawk Airlines opened at Sampson, offering commercial air travel near the city. While passenger trains were still active, air travel was The Next Big Thing.

In December 1953 Mohawk Airlines opened at Sampson, offering commercial air travel near the city. While passenger trains were still active, air travel was The Next Big Thing.

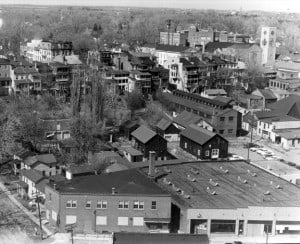

Downtown was vibrant and had everything from 5- and 10-cent stores to separate clothing stores for men, women, and children. The completion of the Routes 5 & 20 arterial in 1954 was welcomed by merchants. For years east-west through-traffic clogged the streets, kept locals away, and didn’t generate sales. The arterial cleared the way for locals to come downtown.

Downtown was vibrant and had everything from 5- and 10-cent stores to separate clothing stores for men, women, and children. The completion of the Routes 5 & 20 arterial in 1954 was welcomed by merchants. For years east-west through-traffic clogged the streets, kept locals away, and didn’t generate sales. The arterial cleared the way for locals to come downtown.

By the mid-1950s there were causes for concern. In 1956, the US Air Force announced the closure of Sampson; locals had hoped the base would become a permanent training station. Manufacturing companies began to close for a variety of reasons. Andes Stove Company never recovered after World War II and closed in 1951. Patent Cereals, Shuron Optical, and US Radiator were all purchased by larger corporations, and gradually were shuttered as operations moved to other regions.

By the mid-1950s there were causes for concern. In 1956, the US Air Force announced the closure of Sampson; locals had hoped the base would become a permanent training station. Manufacturing companies began to close for a variety of reasons. Andes Stove Company never recovered after World War II and closed in 1951. Patent Cereals, Shuron Optical, and US Radiator were all purchased by larger corporations, and gradually were shuttered as operations moved to other regions.

The opening of Town and Country Plaza in 1957 (right) increased the anxiety level among downtown merchants and sparked a five-part series in the Geneva Times about problems in the city center. Parking was at the top of the list of concerns. In 1956 there around 2,000 people employed at waterfront industries, stores, and offices. There was a parking shortage before customers even arrived to shop. There were few parking lots downtown while the plaza had 1,750 parking spaces with no parallel parking, diagonal parking, or pulling out into street traffic.

The opening of Town and Country Plaza in 1957 (right) increased the anxiety level among downtown merchants and sparked a five-part series in the Geneva Times about problems in the city center. Parking was at the top of the list of concerns. In 1956 there around 2,000 people employed at waterfront industries, stores, and offices. There was a parking shortage before customers even arrived to shop. There were few parking lots downtown while the plaza had 1,750 parking spaces with no parallel parking, diagonal parking, or pulling out into street traffic.

The shopping plaza experience was new and modern. One article remarked that “people feel free to go to the shopping center ‘as is’ in slacks, short, pin curls, and what not” while “going downtown” had always been a “’dress up’ occasion and many people still feel obligated to take the trouble to dress more formally before making such trips.”

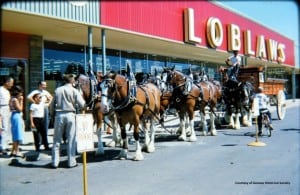

Another aspect of the plaza was the large self-serve stores. Downtown buildings were old and dark, and many still operated on a clerk system. Customers waited at a counter while things were brought to them. Shopping center stores were large, bright, and customers made their own selections, often buying more than they had originally planned.

Another aspect of the plaza was the large self-serve stores. Downtown buildings were old and dark, and many still operated on a clerk system. Customers waited at a counter while things were brought to them. Shopping center stores were large, bright, and customers made their own selections, often buying more than they had originally planned.

The nation was affected by many of these issues. Parts of the country, such as the southern states, were growing as industry left the northeast, but older communities were struggling with change. The 1956 Geneva Times series offered a number of ideas to help downtown with the refrain that “other cities have done this.” Everyone was in the same boat and looking to each other for answers.

Urban Renewal was one such answer. (I will make the distinction between federal-funded “Urban Renewal” and private “urban renewal” demolition and construction projects.) Large scale urban demolition and redevelopment began in the 1930s and 40s, and focused on slum clearance and creating new affordable housing. The Housing Acts of 1949 and 1954 provided federal aid to acquire properties for demolition, and Federal Housing Administration (FHA)-backed mortgages, respectively.

While the idea for federal Urban Renewal may have been discussed in Geneva for some time, the starting point for action seems to be in 1958. A consultant named Floyd Walkley assessed Geneva’s current situation and made recommendations for a master plan. One point was to apply for Urban Renewal. In 1959 the report passed through the city Planning Board and City Council. Mayor Warder stated that “Geneva cannot afford not to adopt an urban renewal program in view of the large amount of Federal and state assistance which could be received.” It was acknowledged that the planning and application process could take four or five years before work could begin.

This proved to be the case. In 1962, the Geneva Times printed an explanation of the proposed program for the public. As a whole, the Urban Renewal program was for “Community improvement, designed to conserve what is good, rebuild what is poor, and to eliminate what is bad in the entire City.” Geneva’s project would target one area of the city in particularly bad condition. Government money, of which the city would contribute one-eighth, would purchase land and property in the Project Area and clear it. The unimproved land would be sold to private interests for redevelopment, guided by what the city felt was needed for the community.

This proved to be the case. In 1962, the Geneva Times printed an explanation of the proposed program for the public. As a whole, the Urban Renewal program was for “Community improvement, designed to conserve what is good, rebuild what is poor, and to eliminate what is bad in the entire City.” Geneva’s project would target one area of the city in particularly bad condition. Government money, of which the city would contribute one-eighth, would purchase land and property in the Project Area and clear it. The unimproved land would be sold to private interests for redevelopment, guided by what the city felt was needed for the community.

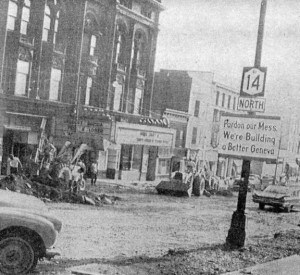

Demolition finally began in 1966. In the second installment, I will talk about what was demolished, what became of redevelopment, and what local projects of the 1960s were privately funded.

Building A Better Geneva: Urban Renewal, Part II

Geneva’s Stories: Urban Renewal in Geneva, Part I

Geneva’s Stories: Urban Renewal in Geneva, Part II