Currency, Finance and the Civil War

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

Banking in the early years of the American Republic was decentralized, inefficient and disorganized, leading to frequent panics and depressions. While attempts were made to resolve these problems, none were substantial or comprehensive enough to put the nation on a solid financial footing. As in many other areas of national development, it was the Civil War which prompted radical change in the country’s financial system.

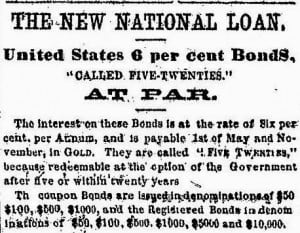

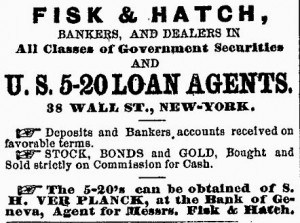

To pay for the men and material needed to fight the war, the government needed to increase revenue. There are three ways to do this: increasing taxes, borrowing funds, or printing money. The U.S. Congress took action quickly, increasing the tariff (the main source of government income to that time) and passing the first federal income tax in August 1861. Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase started the first war bond program in American history to provide loans to the federal government. He sold government bonds both to financiers and ordinary people. By the war’s end, he had sold $400 million worth of “five-twenties”—6 percent bonds that could be redeemed between five and twenty years after issuance—and $800 million worth of 7 percent bonds (“seven-thirties”).

- 1862 newspaper ad for Civil War 6% bonds.

- Ads for the new bond programs appeared in the Geneva newspapers. The local agent was at the Bank of Geneva.

The most controversial action was the 1862 passage of the Legal Tender Act, which allowed the government to print paper money (greenbacks) to pay its bills. Up to this time, the federal government had minted gold and silver coins but did not issue currency. The central government had last issued paper money when the Continental Congress printed dollars during the Revolution, which had become worthless by the end of the war. Fears of inflation, as well as constitutional doubts about the right of the government to print currency, led many Americans to oppose the Legal Tender Act.

The paper money in circulation before the Civil War was issued by individual banks, usually regulated by the states. There was no nation-wide uniform currency and no centralized control of the money supply. Bank notes could be redeemed at an issuing bank for specie (gold or silver coins). Since banks issued more notes than the amount of gold they had in reserve, a bank could easily go bankrupt if too many people tried to redeem notes at the same time (see Banking in Early Geneva).

Bad news on the war front in late 1861 led people to hoard gold. Those who had bank notes exchanged them for gold coins. By early 1862, both private banks and the Treasury were running short of reserves and had stopped paying out gold in exchange for their notes. Though Secretary Chase was uncertain of the constitutionality of the Legal Tender Act, he considered it an emergency measure, writing to Congress in February 1862, “Immediate action is of great importance. The Treasury is nearly empty.” Passed as a war measure, the action was viewed as temporary.

The legislation made greenbacks legal tender for all debts, except custom duties and interest on government bonds—these payments had to be made in specie to shore up the Union’s supply of gold reserves. To maintain these reserves, the new federal currency could not be exchanged for specie. Concern over these unprecedented acts on the part of the federal government actually led many Americans to clamor for higher taxes to pay for the war, rather than printing currency. “Resort must be had to taxes, direct or indirect, or both, to place the government upon a basis of credit which will enable it to command the required means [to fight the war].” Geneva Gazette, January 24, 1862.

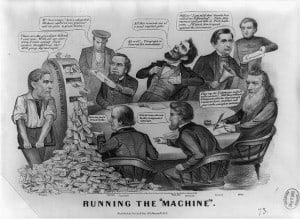

A political cartoon criticizes the Lincoln Administration for printing paper money. Image courtesy Library of Congress.

The change to currency laws enabled the Union to pay its expenses with money it printed. It stopped the run on reserves, but caused inflation. Though far less severe than in the Confederacy (80% compared to 9000%), complaints about the Union’s actions appeared in the press:

Rise in Prices.—Almost every article of domestic consumption has doubled in price within the past two years, and in some instances has trebled; and upon those who depend upon fixed wages, for the support of themselves and family, have fallen heavily. There is no probability, so far as human foresight can see, of any change for the better. Just so long as Government keeps printing greenbacks, in almost fabulous amounts, just so long will prices tend upward of everything that can be bought and sold. A greenback representing one dollar is now worth only about 68 cents.—Geneva Gazette, November 20, 1863

Metal was in short supply for minting coins. Both banks and the Treasury had to resort to printing fractional currency so merchants could make change.

The National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 consolidated and expanded on the changes to the financial system introduced in 1862. Based on New York’s Free Banking Law of 1838, these Acts had three primary purposes: to create a system of national banks under federal regulation, to create a uniform national currency, and to provide a market for government bonds to help finance the Union’s war expenses. The new National banks were required to purchase U.S. bonds equal to one-third of their capital, thus ensuring buyers for the bonds. They were to accept bank notes from other national banks at par or face value, and to circulate Treasury notes (greenbacks) in place of their own bank notes. A 10% tax on bank notes issued by other banks was added in 1865, effectively ending the use of state and private bank notes.

Two national banks were started in Geneva in the 1860s. First National Bank of Geneva was begun in 1863 by several men with Canandaigua banking connections. Three years later, Alexander Chew, Phineas Prouty, Corydon Wheat, Thomas Hillhouse and Thomas Raines bought out the bank and made Chew President. Shortly after, First National constructed a building on the southeast corner of Seneca and Exchange Streets for doing business.

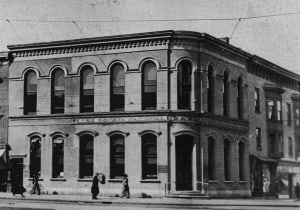

The Bank of Geneva, which dated back to 1817, was re-chartered as Geneva National Bank in 1865. The director was Samuel Verplanck, a former cashier at the Bank of Geneva. The bank was located in the newly constructed Bank of Geneva building at the northeast corner of Seneca and Exchange Streets, directly across from its rival.

Geneva National Bank was across Seneca Street from First National, on the north corner at Exchange Street.

The changes brought about by the crisis of war were the beginnings of the banking system we have today. Questions about monetary policy and economic control of the growing and urbanizing nation would dominate post-Civil War politics, particularly in years when the system failed to cope well with economic upheavals. The next major change to the financial system would emerge at the turn of the 20th century with the Aldrich Act of 1907 and the construction of the Federal Reserve System in 1913.

Sources

Articles on banking and currency at Wikipedia, including:

Grossman, Richard S. “US Banking History, Civil War to World War II.” EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. March 16, 2008. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

Jaremski, Matthew. “State Banks and the National Banking Acts: A Tale of Creative Destruction.” November 2010. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: the Civil War Era. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1988.