To Strike or Not to Strike

By Becky Chapin, Archivist

In 1833, a group of journeymen shoemakers from Geneva were taken to court over a strike attempt. In People v. Fisher, the shoemakers, as defendants, had gone on strike in an attempt to maintain a wage standard when a master employed a journeyman for less than their standard wage. The result was the presiding judge held the journeymen indictable on a conspiracy statute, the first American application of such as statute on labor activity.[i]

A few years later, this would be overturned in People v. Cooper when the defense counsel questioned the validity of using English precedents in American rulings.[ii]

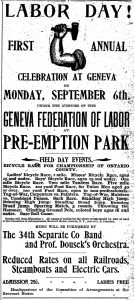

Organized labor unions wouldn’t come to Geneva until the end of the century. In fact, an explosion of organizations occurred in 1897 with dozens of unions forming for a total of 500 members altogether. A new column was added in the Geneva Gazette that would give union news from the local and national levels. The Geneva Federation of Labor would bind Geneva’s unions together, starting the first Labor Day celebration in 1897.

One of the first applications in Geneva was the early closing movement in 1898. Dry goods, clothing, and hardware merchants agreed to close their stores no later than 7 PM, four days a week. Previously these stores would have been open from 7 AM to 9 PM every day except Sunday. While the movement was first taken on by the merchants, their clerks followed soon after.

As the people who are kept in the stores with stragglers, clerks could stay as late as 10:30 PM. If they could be given a set time at which to lock the doors, the clerk “…can get a breath of fresh air for a change, which will do him as good in one night as the money he makes keeping open in the evening…” said “a clerk who appreciates an evening when he gets one.”

New unions would be formed as the 19th century gave way to the 20th century, mainly for men. The first all-women’s union was formed with a local branch of the United Garment Workers in 1901. The union was made up of employees of the TF Barnes overall factory on Exchange Street. After organization, the company agreed to their terms of a nine-hour day and to give employees a half-holiday. Notably, all the elected union officers were unmarried women.

Geneva would join with Canandaigua and Auburn to form the Tri-City Labor Alliance, whose main purpose was to organize the Labor Day celebrations. By 1908, the group did away with large Labor Day celebrations as the participants preferred having most of their holiday to relax.

Additionally, the alliance wanted to make an “earnest effort to organize the woman workers within their territory… nine tenths of woman workers and housewives are the purchasing power and if organized would assist in the agitation for the union label which is at this time very essential to organized labor…” This meant if women were part of unions, they would advocate to purchase only products made by union workers.

There were some notable local strikes in the 20th century. In 1921, the Builders’ Association went on strike over wage scale differences between the builders of the city and the unions of the building trades. From July to August, builders in the city stopped work on projects, though some continued independently (allowed by the union) when they were paid at the old wage scale. Outside arbitrators were brought in and new wage scales were fixed and approved by both parties.

The Local 2371 International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAM), Hulse Manufacturing employees went on strike in 1969. The strike was called by the union when demands for a higher wage and a closed union shop were denied by management. Hulse’s parent company, Smith-Corona, started importing German products and hiring strikebreakers to replace those on strike.

Two months into the strike, negotiations were going well until the company wanted to implement a ‘reverse seniority’ system which would give new employees, and other company favorites, super seniority over employees who had been with the company for decades. From June to November, the strike continued. Union American Can Co employees joined the picketers when they could. Hulse brought the issue of picketing outside the factory to court. Eventually, IAM members voted in early November to accept a one-year contract, and the strike was settled with no closed shop, but a modified version.

[i] Mayer, Stephen. “People v. Fisher: The Shoemakers’ Strike of 1833.” The New-York Historical Society Quarterly 62, no. 1 (January 1978).

[ii] Carnegie Institution of Washington, American Bureau of Industrial Research. A Documentary History of American Industrial Society. The A.H. Clark Company, 1910.

The Catchpole strike was very big. As were the nursery strikes.