Almanacks; Or Predicting the Future

By Becky Chapin, Archivist

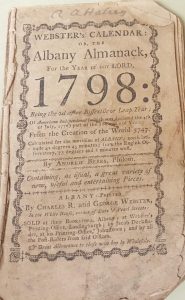

Albany Almanack, 1798

The Archives holds quite a few almanacs, both international and local, in its collection. I recently found one from England which, unfortunately, was falling apart and it inspired me to look into the history of almanacs in general and examine the almanacs formerly owned by Genevans that have now come into our possession.

The first printed almanac appeared in Europe in 1457, but almanacs have existed in some form since the beginnings of astronomy. Almanacs contained a calendar of the days, weeks, and months of the year; a record of various astronomical phenomena, often with climate information and seasonal suggestions for farmers; and miscellaneous other data such as the phases of the sun/moon, positions of the planets, high/low tides, and dates of festivals and saints’ days.[1]

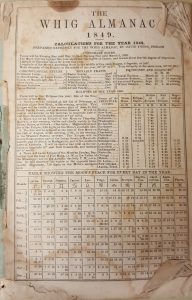

The Whig Almanac, 1849

The first almanac printed in colonial North America was An Almanac for New England for the Year 1639, compiled by William Pierce and printed in Cambridge, Mass., under the supervision of Harvard College. One of the most popular publications in colonial America was the Poor Richard’s Almanack which was published by Benjamin Franklin from 1732 to 1760, under the pseudonym of “Richard Saunders.” These books were popular due to Franklin’s unique writing style. Richard’s Almanacks not only included the typical yearly information, but jokes, hoaxes, puzzles, practical household hints, and witty phrases and wordplay. The oldest almanac still in circulation in North America is the Old Farmer’s Almanac first published in 1792 by Robert B. Thomas,[2] of which we own a few copies.

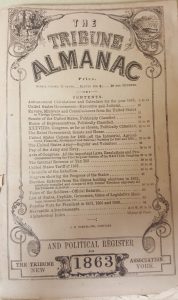

The Tribune Almanac, 1863

The archives holds several almanacs including one dating back to 1741, once owned by a family who lived on William Street (though when they lived there is unclear), which was published in Boston. Other almanacs we hold were published in Albany, dating back to 1798 and 1819, and called “Webster’s Calendar: or; the Albany Almanack.” Often almanacs were connected to political movements; the “Whig Almanac ” for the year 1849 contained historical, political, and statistical information of the Whig Administration and cost 12 ½ cents. It included a review of the 1848 election in the United States with General Zachary Taylor as President and Millard Fillmore as Vice President whom were both nominated as candidates at the Whig National Convention. The 1848 election was significant in that it was the first presidential election that took place on the same day in every state and it was the first time that Election Day was statutorily a Tuesday.

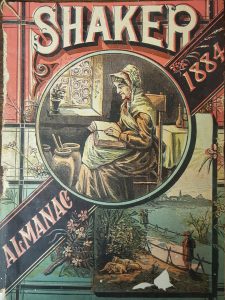

Shaker Almanac, 1884

Other almanacs include “The Family Christian Almanac,” which gives a resounding essay on temperance, and “The Tribune Almanac ,” whose 1863 edition lists members of ‘The Rebel Government’ of the South and gives a ‘Chronicle of the Rebellion.’ “Dr. O. Phelps Brown’s Shakespearian [sic.] Annual Almanac,” “Jayne’s Medical Almanac and Guide to Health,” and the “Shaker Almanac” are just a few other publications made in America which were once owned by Geneva residents.

It’s really fascinating to look at what was important to Americans in each year and it’s incredibly impressive that humans were able to make (true!) predictions so early in history and publish them for others to use in their own lives.

[1]The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Almanacs,” Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/almanac.

[2] Benjamin Franklin Historical Society, “Poor Richard’s Almanack,” http://www.benjamin-franklin-history.org/poor-richards-almanac.