A Digital Dark Age

By Becky Chapin, Archivist

Way back in February 2021, I wrote a blog called Why Don’t We Just Digitize Everything? in which I explored how archivists use digitization as a tool for preservation and access of physical materials. But as our lives are becoming more and more digitally reliant, meaning we rely less and less on passing down our stories in a physical way, the question becomes how do we preserve materials we can’t even touch?

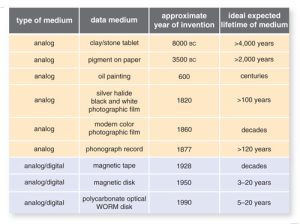

What is the digital dark age? Many people have been warning about a digital dark age as early as 1997. It refers to problems which arise due to obsolete file formats or physical media that requires special hardware to be read that is no longer available as I covered in my previous blog.

I don’t know the number of people who use smartphones as a method of taking, storing, and saving photos and communication, but I think it’s safe to say it’s in the billions. Writing letters to family and friends has quickly become a lost form of communication. Instead, text messages, emails, and phone calls in the 21st century replaced physical remnants of how people interact.

Phones automatically delete texts after a certain amount of time. If your email company goes out of business, those emails stored on their servers are gone unless you manually export them and import them into another software. Communication on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, dating apps, and other social media sites are accessible only to you- and only for the time you have that account.

One magnetic reel-to-reel tape, like those in our A/V Collection, stores less information per meter than a 1 terabyte hard drive. That means more data will be lost if that hard drive is corrupted, whereas on the magnetic tape we may lose one or two seconds.

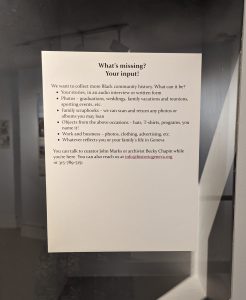

In our exhibit, “Lift Every Voice,” Curator John Marks deliberately left a display case empty to request help with growing our collection and saving the stories of our community. This also shows that we have gaps in our collection in late 20th century and 21st century material.

Many information scientists, archivists, archaeologists, and others believe we are presently in a digital dark age. In 2018, Rick West[sp.?], then managing data preservation at Google, said to the Science Friday radio program, “We may know less about the early 21st century than we do about the early 20th century” because early 20th century is still based on paper, whereas much of what we’re doing now is born-digital and increasingly dies as digital content without ever being physical.

Since 1996, the Internet Archive has been working to prevent a digital dark age by compiling periodic digital snapshots of the web for its Wayback Machine. They expanded to digitizing books, audio recordings, videos, images, and software programs that today equal over 99 petabytes for one copy of their system.

99 Petabytes. 1 petabyte is 1,024 terabytes. Your average 2023 hard drive measures 1 terabyte. And the Internet Archive keeps 2 copies of its system. So that’s over 200 petabytes of data that they are dedicated to preserving. And it continues to grow every day. As of today, their website contains over 819 billion webpages, 38 million books, 10 million videos, 15 million audio recordings, 2.5 million television shows, and much more.

This short documentary from 2013 about the Internet Archive is incredibly interesting and I highly recommend it. Fun fact, since late 2009 the headquarters of the Internet Archive has been in a former Christian Science building.

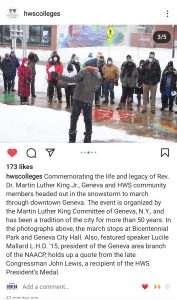

We often get asked, what do you collect? Our newest exhibit, “New Acquisitions,” highlights just some of the objects and archival material that we’ve added to our collection in the last few years. It doesn’t show how we’ve been saving born-digital files like Instagram posts from our community.

So, what do we do to ensure longevity of our digital files? Some simple suggestions include making regular back-up copies of your files/photos, like on a hard drive or a cloud-based system. When changing software or computer hardware, try reading documents, images, or video and convert them to new formats if necessary. If possible, print out highly important documents and photos and store them safely in cool, dry spaces.

A final question: how do you think historians in the future will be able to interpret our daily lives?

Feel free to ask me questions about how we can help you preserve your stories, physically or digitally, at archivist@historicgeneva.org.

Thank you Becky. Important information and the documentary is fantastic.

Pim

A great and timely blog article, Becky. It will be up to the archivists, historians and librarians to save as much history as they can in this “digital dark age”. Thanks for writing about this problem.