19th-Century Corsets

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, the heavily structured corsets discussed in our first post disappeared as high waists on loose gowns became fashionable. Early 19th-century corsets were simpler and softer. Undergarments were designed to support the breasts just under the bust and to smooth the figure. Cording and a center busk helped achieve this by pushing up the bosom while flattening out the hips and creating a columnar shape.

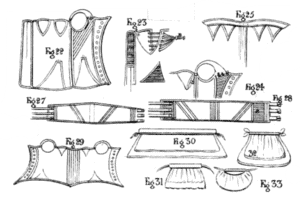

This 1830 image from the women’s magazine Godey’s Ladies Book shows fashion’s return to a narrow waist.

From the 1820s, the fashionable waistline gradually dropped back to its natural position, but the corset remained similar in construction. Widening the gores at the hip and bust line made it possible to pull in the laces at the waist, creating an hourglass figure instead of a column. Fuller skirts, padding, and wide sleeves made this shape more pronounced in fashionable dress.

Miss Rodgers worked out of Robert Rodgers’ upholstery shop on Main Street, but also made house calls.

The type of corset worn in the early 19th century was readily produced at home. Many early American women probably made their own corsets, although dressmakers, like Miss Rodgers in Geneva, also produced them.

The Workwoman’s Guide, an English book printed in 1838, instructed middle class women on making and maintaining clothing and linens for their households. It included corset patterns for women, sportsmen, and children.

We don’t have much information on Geneva women’s experience of corsetry. In letters and diaries, women rarely wrote about their clothing, much less their undergarments. We do have a few corsets in our clothing collection, though we rarely have information about who owned them. Most of them were factory made in the early 1900s, however, one is similar to those in The Workwoman’s Guide.1 It is made of pinstriped and plain cotton and is entirely hand sewn, including the lacing holes. The corset is plain and was very likely homemade for everyday wear.

- An undated stay, or corset, from the Geneva Historical Society collection.

- This metal busk was bent and shaped to fit the corset wearer’s shape.

- This corset is stitched by hand, indicating it was produced in the early to mid 1800s.

Through the mid-19th century, corsets, like this one, laced up the back and had a busk, a flat strip of ivory, wood, bone, or metal extending down the center front, to create the flat front and upright posture required by fashion and decorum. The metal busk from this corset was bent to fit the curve from the original wearer’s waist to bosom.

Like many early 19th-century corsets, this corset does not contain whalebone, but has cording to provide support and shaping. Cotton or linen cords were sandwiched between one or more layers of fabric to give the garment a soft structure that would conform to the individual figure with wear. Whalebone—which is not actually bone, but baleen—was the preferred material for shaping clothing throughout the years of corset use, particularly when more extreme shapes were fashionable. It is strong, but flexible. It conforms to the body over time and provided custom-fitted structure to all sorts of garments. Boning, cording, reed or other materials enabled the corset to form the body into whatever shape was preferred by fashion at the time. Corset boning began to appear more frequently as a narrow waist became fashionable at mid-century.

- Julia Post Swan lived in New York City. Her fashionable dress in this portrait reveals the stiff busk of her corset.

- By the late 1850s, Margaret Swan is wearing the new style corset with a short waist and and rounded bust.

By the 1850s, boning, piecing, and gussets had reshaped the corset and the fashionable form. Complicated patterning, plentiful whalebone, improved steel technology, and the development of the front-fastening busk meant corsets became better at shifting the flesh to create the appearance of a small waist. You can see the difference in these two portraits of women in the Swan family. Julia Post Swan was married to Robert’s brother Edward. She lived in New York City and was likely at the height of fashion. In this photo from about 1850 you can see how her corset smooths the line of her bodice but also leaves a characteristic horizontal line across the bosom. This is common in the dress styles of the 1840s and early 50s. The waist of her dress falls below her natural waistline, and the long, straight line of the front busk also forces her into a slightly reclined posture. In Margaret Swan’s picture from c. 1857, we see how the new fashion moves the waist to the natural waistline. The corset is shorter and creates a rounded bosom and short, narrow, defined waist.

Fashion and technology continued to reshape women’s bodies through the early 1900s. Corsets and patterns became more complicated and challenging to construct. Fewer women made them at home. Wealthy women continued to have them custom made, but corsets also started to be mass produced in factories. In our next post we will look more closely at industrially produced corsets in the Geneva Historical Society collection.

Footnote

[1] Although dated 1870 when added to our collection, the corset is not the style for this late in the century. It was likely worn sometime between the 1830s and 1850s. The sewing machine was invented in 1846, but was not common in households until the 1870s.

Links and Sources

American Duchess Podcast: Corsets with Cathy Hay of Foundations Revealed

Thanks! I’m doing research for my novel. This helps.

Didn’t these women do any work? You cannot clean a house, plant a garden or ride a horse dressed like that. Did they wear corsets all the time, or just for photographs.

Also, I’d like to know why fashions changed so drastically. Short skirts, stocking, etc. My guess is it was because of automobiles and public transportation. No one could drive a car dressed like these ladies dressed. (Not to worry, cars were not around then)

Did poor women wear corsets?

I am sorry to be so late in replying. Due to a technical issue with our notification system I only just saw your comment. Most women did pretty much wear corsets all the time. You will find more in-depth discussions in the related links, but in short there were different types of corsets for different levels of activity. A high-fashion boned corset was not what you wore around the house. Soft corded corsets are no more confining than many modern undergarments, as attested to by many modern re-enactors and living historians. Fashionable dress, as seen in our images, was only available to the wealthy. These women did not have to do manual labor. They could wear different garments for more rigorous activities, and whether those were appropriate activities for “ladies” (they were always appropriate for the working class and enslaved) was a source of debate in the 1800s.

I would argue that changing ideas about what was appropriate for women was why fashions changed so much. The bloomer that was outrageous in the 1850s became the athletic wear of the 1890s when golf and bicycling became popular with women. You will find more on some of these topics in our other posts on fashion: https://historicgeneva.org/blog/fashion-and-clothing/