Briefly Out of Fashion’s Bondage

By Alice Askins, Education Coordinator at Rose Hill Mansion

Since the dress reform movement of the 19th century has been studied and discussed at length (Patricia Cunningham’s Reforming Women’s Fashion, 1850 – 1920 is a good example.) I will not re-tell that whole story. Instead, I will talk a little about the Bloomer costume and the Geneva area. A Bloomer dress (so named because Amelia Bloomer promoted the style in her magazine The Lily) was a dress much like the fashionable dress of the day, but with a shorter skirt and loose trousers under it. It looks modest and unalarming to modern eyes.

The Bloomer was invented by Elizabeth Smith Miller, who later moved to Geneva and lived here for the rest of her life. Her role was probably not generally known in the 1850s and the local papers do not mention it until 1894. It was in 1851 that the Bloomer dress made its first appearances in public.

Geneva Daily Gazette May 2

SHORT DRESSES. – Mrs. Bloomer, editor of the Lilly [sic] has adopted the “short dress and trowsers,” and says in her paper of this month that many of the women in that place, (Seneca Falls,) oppose the change; others laugh; others still are in favor; “and many have already adopted the dress.” She closes the article as follows:

“Those who think we look queer, would do well to look back a few years, to the time when they wore ten or fifteen pounds of peticoat [sic] and bustle around the body, and baloons [sic] on their arms [that is, big sleeves], and then imagine which cut the queerest figure, they or we. We care not for the frowns of over fastidious gentlemen . . . If men think they would be comfortable in long heavy skirts, let them put them on – we have no objection. . . .”

The Gazette made no comment on the Bloomer’s debut. It simply reported that “Over two hundred females, dressed in the Bloomer costume, attended the churches in Cleveland, Ohio, on the 13th inst.” (July 25, 1851)

By August, though, there is a hint of uneasiness evident in a silly poem:

A Bloomer.

Ye muslin dresses, white and thin,

With fairy finger’d stitches on;

I fear your day has passed away

Since woman put the breeches on.

Ah! well a day, the Bard may say,

Shall one bestow his kisses on

A shameless maid, who’s not afraid

To put a pair of breeches on[?]

She’ll make him feel from head to heel,

Whatever else he hitches on;

He’ll have no right by day or night,

To put a pair of britches on.

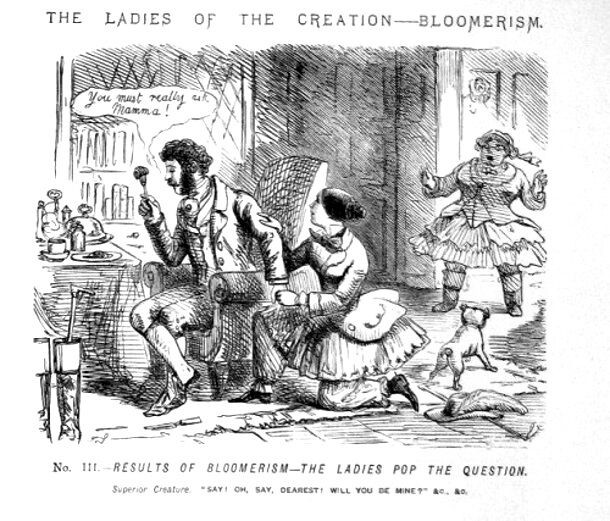

Suddenly the Bloomer is the garb of shameless women. The really sinister verse, though, suggests that men will soon have no right to wear pants. A common motif in cartoons and protests about the Bloomer was that women, by donning loose trousers in public, were attempting to reverse the spheres of activity and the power relations of the sexes. “Women are trying to be men!” cried the cartoonists. “They will try to make us be women!”

Women often wore the Bloomer outfit for purely practical reasons. Certainly, Mrs. Miller created it in frustration with the inconvenience of long, heavy skirts and petticoats – which swept the streets and soaked up water in rain or snow. Imagine, too, having to go upstairs while carrying a baby. The Gazette also tells us about a woman who wore the Bloomer on a trip across the Isthmus of Panama, without feeling obliged to judge her choice of travel wear (April 8, 1853.)

It is nevertheless true that the wearing of distinctive dress, however comfortable and practical, can have political significance. Feminists saw fashionable dress, not unreasonably, as oppressive. Mrs. Miller’s cousin Elizabeth Cady Stanton asked, “Is being born a woman so criminal an offense that we must be doomed to everlasting bondage?” Wearing the Bloomer in public, therefore, was a statement. It was also most common among women who were already involved in other reform efforts. The local paper certainly associated the Bloomer costume with political activism. In October 1851, the Gazette reprinted a story from the Argus:

[When abolitionism] finds a lodgement in the female bosam [sic], it not unfrequently delights to exhibit itself in the opposite extremities. It was so, on the occasion of the examination of the Syracuse rioters and rescuers, before Judge CONKLING. [This would be the Jerry Rescue – it’s in Wikipedia.] It is said that on the last day, among the crowd in the court room, were several ladies from Syracuse, dressed in the Bloomer costume, who created considerable excitement . . .

The following spring, the Gazette printed a piece from the New York Observer that took a very sour attitude toward “Bloomer women.”

April 9 1852: [Fourteen] women have issued an “Appeal for the freedom of American women,” in which they complain that they have been for many years oppressed, and their health injured, by the dress adopted by the women of our country, and that because they have sought a remedy for their wrongs by adopting the “Bloomer” dress, they have been met . . . by “a uniform system of insult and outrage,” being followed by a rabble, hissed, hooted, and insulted. . . . we suppose the treatment they [receive is the] natural result of the peculiar style [they have] adopted. Any strange object, that excites great curiosity, will draw after it a crowd of men and boys, who have nothing better to do. We suppose a man dressed in women’s clothes, would have encountered the same rabble; and in either case the remedy is at hand – the police. Whether they have encroached on the scripture injunction, which forbids females to assume the male attire, we do not undertake to decide [they said, having obviously decided]; but any approach to it would be naturally followed by just the treatment they have received. . . .

The Bloomer women say . . . that they are ready to die for their principles, and if so they will surely be able to stand a few hisses when they make themselves ridiculous.

Eventually most of the women who had tried out the Bloomer dress returned to fashionable clothing, for public appearances, at least. Whatever its advantages, the reform dress caused so much panic that its wearers came to see it as a hindrance to the other causes they were trying to promote. While people were focused on clothing, they could not listen to ideas. As the Geneva Courier reported in May1856, “Miss Lucy Stone Blackwell has repudiated Bloomers, and appeared on the anti-slavery platform in New York, in a long black silk dress, fashionably beflounced.”

For more information on Mrs. Miller creation of the Bloomer costume read “Everything is Coming Up Bloomers!”

who is the author of the bloomer poem, where did it come from. I want to cite it in my essay lol.

The staff member who wrote this post no longer works with us so I don’t have her source. It was probably the local newspaper, as you will find the poem in several online newspapers from 1851 if you search the words. One Indiana newspaper cites the source as The Knickerbocker, a New York literary magazine of the time.