Food Preservation: From Home to Factory

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

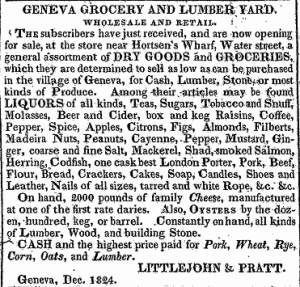

By the 1820s many Finger Lakes settlements were well established. In town, supplies would arrive with some regularity. Water transportation routes had been improved, and Indian trails had been widened and turned into turnpikes that ran regular stagecoaches. Geneva grew quickly in part because Seneca Lake and the Seneca River were navigable for most, if not all, of the year. By 1821 Geneva grocers were regularly offering imported goods like fresh lemons and limes, pimentos, coffee, tea, rum, molasses, sugar, wine, gin, raisins and chocolate. Trade was well under way, but exploded with the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825. Not only could farmers finally sell their produce to larger markets, far more goods could be brought into the communities along the canal system. As historian Carol Sherriff details in her book The Artificial River, the arrival of fresh oysters in western New York shops was a symbol of the progress achieved by its construction.

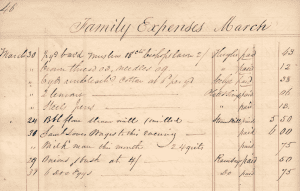

As goods became more plentiful and trade more reliable, families that had ready cash or goods to trade no longer had to grow or preserve all their own food. Many farmers like Robert Swan and John Johnston had smokehouses for producing hams and other preserved meats. Some of this meat may have been sold to grocers in town. Living on South Main Street in 1847, banker William Sill’s wife recorded purchases of beef, fish, veal, mutton and occasionally poultry from butcher H. H. Merrell. Purchases included salt salmon and smoked beef. Mrs. Sill also bought large quantities of salt and vinegar, so she or her servants may have been preserving some of their meat at home. Cornelia Bogart Grosvenor, the wife of a Geneva lawyer, recorded dozens of hand-written recipes in a notebook, from her 1827 marriage to her death in 1886. She kept recipes for pickled oysters, preserved watermelon, fruit marmalade, lemon jelly, pickle for 100 pounds of ham, and H. H. Merrell’s recipe for the “Celebrated Method of Curing Beef in Tunis.”

In 1809, French chef Nicholas Appert discovered that boiling food in a sealed bottle kept it from spoiling. By 1823 New Yorker, Thomas Kensett, had secured the first patent for the tin can, which provided a cheaper and stronger container for preserving food using Appert’s method. The first foods to be preserved were highly perishable fish, and expensive cans of salmon and lobster were luxuries not available to most families. After the development of the Mason jar in 1858, women at home could also easily use this method to preserve food. Just two years later, Genevan Adelaide Prouty complained about these advances in preservation:

Bottling fruit the new fashioned way. Oh for the simple ways and plain living of olden times, when plain dinners and a few dishes were enough for the wants of a family. But now look at it–Soups, fish, meats, vegetables, puddings, pies, fruits, ices. And then the preparation for tomatoes. Fruits bottled, canned & dried, pickled, preserved & brandied. Vegetables, put up green, ripe & in every stage. It is enough to make the fall a season to be dreaded and a housekeeper’s life one of drudgery & weariness.

As reliable supplies of food became normal and standards of living rose, expectations rose as well. Women who could, were expected to provide more variety in their family’s meals. The new methods of preservation enabled greater consumption and became status symbols. Ironically, the hard work of preserving food for survival was transformed to hard work for the sake of conspicuous consumption.

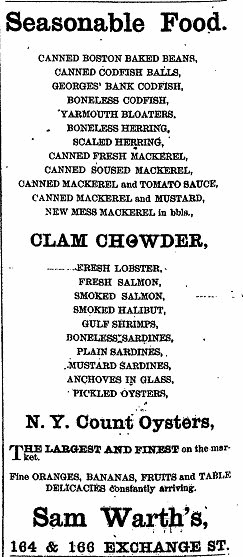

The government’s need for cheap, transportable, spoilage-resistant food during the Civil War proved a boon to the canning industry. Soldiers all over the country came back from war with a taste for canned pork and beans, and the industry exploded. By the 1880s, grocers routinely advertised canned goods like baked beans, corn, tomatoes, and canned fish.

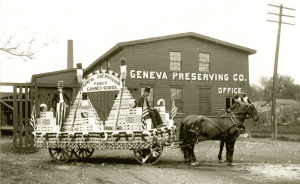

In 1889 the Geneva Preserving Company started canning produce from area farms and distributing their products across the country. In the first years, a few thousand cans were produced each year. Production was time-consuming because cans were handmade, and most fruits and vegetables had to be processed by hand. Twenty-two years later, the manager of the company reported that they were growing produce on 300 acres of land, using machines to process produce, and handling 500 cans a day. Their business amounted to half a million dollars in 1911.

Despite advances in factory canning, many people continued to preserve their own food. Farm families still preserved food for sale in markets. Cornell Cooperative Extension distributed information leaflets in the early 20th century explaining the process for preserving food safely for home consumption or sale. Home preservation regained importance during the World Wars, as canning facilities were converted to war time production and canned goods were reserved for the military.

Innovation combined with continuing improvements in living standards in the 20th century to make home food preservation a lifestyle choice, rather than a necessity. Technological and social changes made electricity, refrigerators and stoves necessities for a household, rather than options. Frozen foods, TV dinners and convenience foods became accessible to the average family. Cooking, much less home food preservation, became something of a lost art. Low-cost fast food and convenience food have again transformed American households, apparently making cooking itself a luxury activity. According to one poll in 2010, only 41% of American adults cook five or more times a week and 11% never cook. At the same time, locally-sourced, organic, and homemade products have been transformed into high-end items for “foodies,” while governments and social welfare organizations consider ways to get the poor to consume more healthy, fresh food. History may simply prove that only change is inevitable.

Sources:

Chicago Tribune Eating & Dining Staff. The Stew Blog

Orsamus Turner. History of the Phelps and Gorham Purchase

Tagged With: 1800s, Anne Dealy