Workers at Rose Hill Farm

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

|

| Workers harvest potatoes in the apple orchard at Rose Hill, c. 1885. |

As we saw last month, the Swans at Rose Hill relied on female workers to do much of the housework and childcare. Running the farm operations required male workers. The farm consisted of about 350 acres for most of the Swans’ residency. The primary crops were wheat and oats. Livestock raised included cattle and sheep. Searching for information about the farm workers is slightly easier than finding out about the domestic workers because the men never changed their names and are usually identified by occupation in the federal census. In addition, while women are rarely listed in the Geneva Village Directories, but most men are.

Many more male workers are also mentioned in Robert’s personal and business papers. The account book mentioned in my post on domestic workers has far more men listed. This account book is not organized as the record of a modern business might be. It includes comical sketches of Robert’s brothers, a list of personal expenses for 1846, a prayer, and payments to workers and suppliers, as well as signed contracts with some workers. The farm records date between 1852 and 1862. Robert also kept a memorandum book, or farm journal, which has brief notices of what was being done on the farm and includes the occasional personal comment. He wrote in this book between 1851 and 1858, mostly during the winter and summer months. Occasionally a worker is mentioned in a family letter, but this is rare.

Robert Swan employed workers to do a variety of tasks on the farm. Some plowed, planted and harvested the crops sold at market or grown to feed livestock. Most of these crops were grains and other grasses which had to be cut, tied and dried in stooks (stacks) before being drawn into a barn and threshed. Men hauled manure and plaster and spread them on the fields and dug and removed stones from fields. They cut and hauled ice and timber, hoed and weeded the garden and fields, and built and repaired fences, rails and buildings.They also washed and sheared the sheep, slaughtered pigs and fed the livestock. A large part of their work was just hauling things from place to place. Although Robert Swan used a reaper, and employed threshers with a threshing machine, his workers also used manual scythes and did many tasks by hand.

|

| Illustration of man lowering drain tile into a ditch. |

A major project Robert undertook during his first few years on the farm was draining the fields using the principles he learned from his father-in-law, John Johnston. Workers were hired to dig drainage ditches, bring the drain tile to the fields, lay it in the ditch and cover it over. By the end of 1853, these men dug, by hand, over 17 miles of 2-foot-deep ditches around the farm. The pay for this back-breaking work was about $40 per mile per man. Labor was so cheap relative to materials, that it actually cost Robert Swan more to buy the tiles and have them delivered to the farm than to pay men to dig the ditches.

|

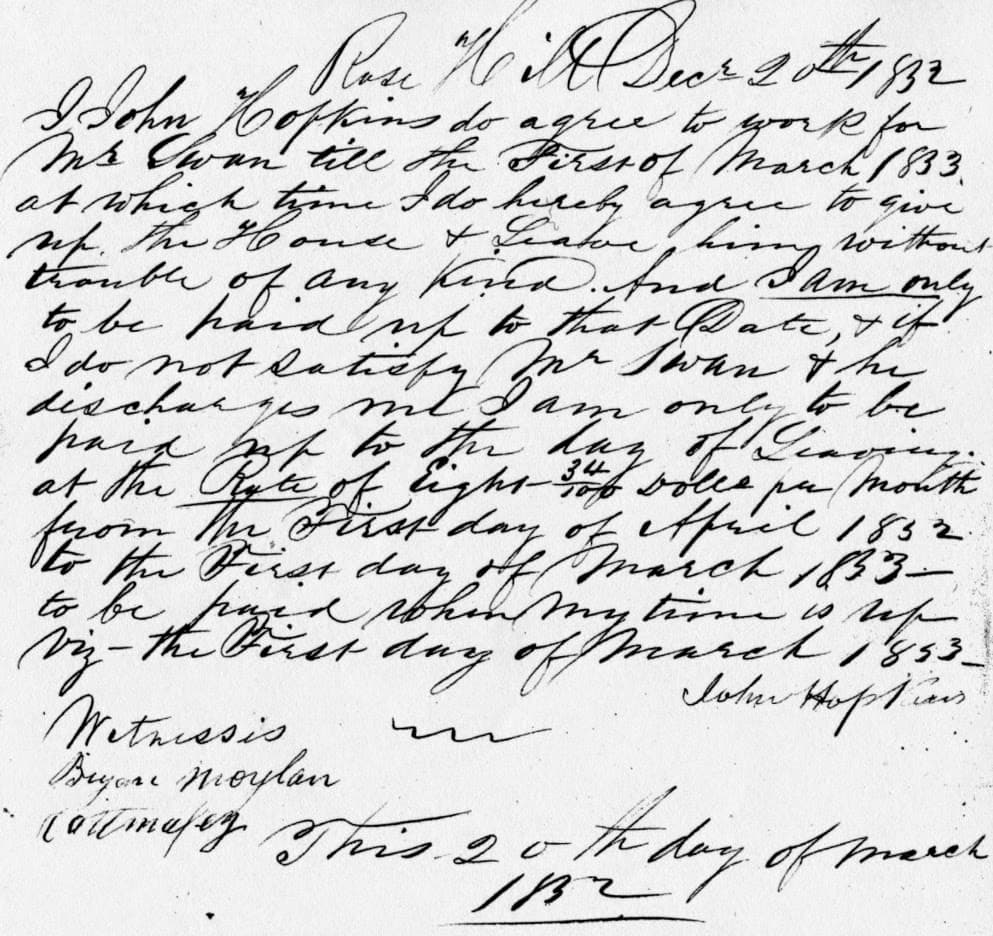

| Contract engaging John Hopkins to work for Robert Swan. |

The farm work was done by a variety of men. Some seem to have been neighboring farmers or their sons looking for extra work. A few were specialized workers, like the threshers, but the overwhelming majority were Irish immigrants. Many were hired for a specific task or period of time. Men were hired for haying and harvest. Some were hired just for ditch digging or threshing. A major category of employment on the census during the 19th century was “farm laborer,” “day laborer” or just “laborer.” Some of the men hired stayed on for a year or more. Many of those were given a contract of sorts, written up by Robert and signed or marked by the employee. Most contract workers were paid $8 to $10 per month for a year’s work. Contracts specified that pay would be pro rata if they left early, and included provisions like: “I Patt McGuinis do hereby agree to work for Mr Swan…and do further agree to be faithful in my duty & to do anthing [sic] Mr Swan tells me, & to be pleasant, to keep sober & not to have drink or liquor in my house.”

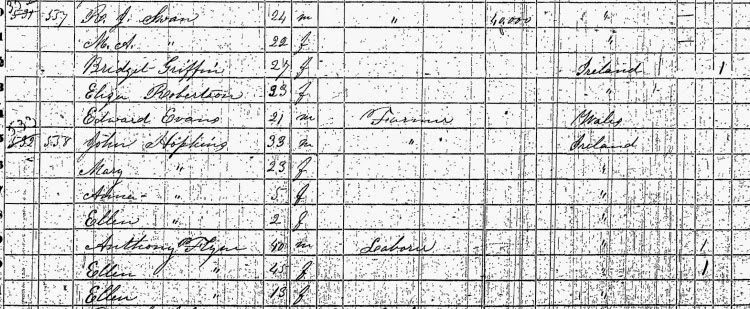

Many of the workers lived on the property. Two are listed in the 1860 census as residents of the household; others occupied one of the three tenant houses located on the farm, often with family members. John Hopkins lived next door in 1850, with his wife, two daughters, another farm laborer and his wife and daughter.

|

| The 1850 Census lists the members of John Hopkins’ family in the house right next door to the Swans at Rose Hill. |

Swan didn’t seem pleased with Hopkins’s work, writing at the end of the contract, “John Hopkins time is up to day and I have paid him off & am glad to get quit of him.” Hopkins may have lived in the house prior to the Swan purchase of the property and his contract stipulated that he would give up the house without trouble. Several others were let go without regret, two for requesting higher wages, one for being impudent, and another for missing work. There seems to have been no shortage of workers.

|

| One of the tenant houses at Rose Hill, c. 1885 |

Based on the sources we have, Robert Swan actively managed the farm during his first ten years there. In 1860, however, he began to have health problems, and he listed the property for lease in the Geneva newspapers. It is unclear whether he ever went back to full time farming. Though the farm continued to be worked, we don’t know how involved Robert was in the day-to-day activities and management. His account book, which contains contracts with his workers, only extends to 1862. In that year, he leased the farm to a Mr. Henderson, an arrangement renewed in 1863, when he noted receiving $2100 annual rent from the man. Mr. Henderson is also mentioned in other material later in the 1860s and must have leased the farm for several years.

There were still workers on the farm after this. In a photograph album of the 1880s we see some of these anonymous men at work harvesting potatoes in the orchard or working in the hay barn, unfortunately we know little else about them.

Do you know the origin of or the artist that did the woodcut -“Illustration of man lowering a drain tile into a ditch”?

Unfortunately we don’t seem to have that information. The image can be found in Mike Weaver’s History of Tile Drainage in America Prior to 1900. It is stated that it was engraved on one of the two cups given to Johnston by the New York Agricultural Society in 1859 for his work in tile drainage. A description of the cups and a pitcher can be found in the Ag Society’s Transactions on Hathi Trust here: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101050721826;view=1up;seq=190. There is a photo in Weaver’s book of the set as well. I believe we have one of the cups at the Johnston House, but as it is not accessible to me at present I can’t say if it includes the image. I don’t know if there is an existing woodcut or if the Weaver image was reproduced from the cup. I hope that helps.