Patent Medicine

By John Marks, Curator of Collections and Exhibits

I have become a digital version of my father. Before any project he would lay out old newspapers. Even though he’d read them already he would read them again, the project forgotten. When I go to nyshistoricnewspapers.org to begin one project, I find many other things to distract me.

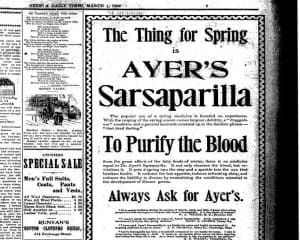

I love the language and graphics that old advertisements used. In any 19th-century Geneva newspaper many of the ads were for patent medicines that could cure any and every illness. The name sounds like the medicine formula has been registered with the United States Patent Office. Rather, it came from Europe in the 1600s when a product received a royal endorsement through letters patent.

An actual patent would require makers to reveal their ingredients, which was the last thing they wanted to do. Most patent medicines contained high levels of alcohol, or alkaloids like morphine. They did make the patient feel better but didn’t cure anything. Without antibiotics or the ability to treat diseases like cancer, feeling better was the best for which one could hope.

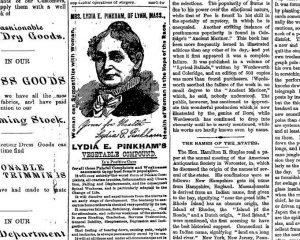

Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound is one of the more famous patent medicines. It was a blend of herbs, roots and alcohol. It claimed to cure “female complaints” which may have ranged from menstrual pain to more serious diseases.

![]()

“Female complaints” were a lucrative market. Exotic names helped sell products. “Catholicon” is just an old word for panacea or universal remedy. Many products associated themselves with foreign cultures or Native Americans to seem more legitimate.

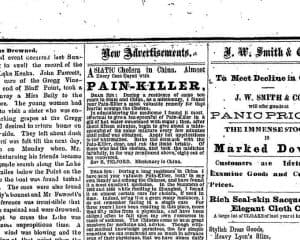

Testimonials were another popular tool. If a minister who lived in China said this worked, then it must have been so.

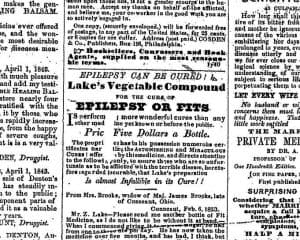

Diseases such as cholera and diphtheria spread quickly through towns and were often fatal. Other conditions such as epilepsy couldn’t be diagnosed or understood. Fear and helplessness drove many people to try these guaranteed remedies.

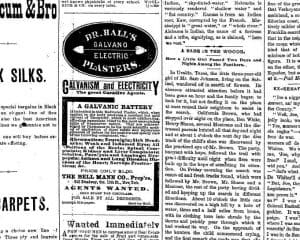

Some medicines appealed to science. Electricity was thought to be a new miracle cure.

Some medicines appealed to science. Electricity was thought to be a new miracle cure.

The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 was the first law to require accurate labeling of ingredients. Later acts tightened the regulation of fraudulent claims. Many products disappeared but others survived. Some were effective for specific symptoms, such as Bromo-Seltzer, BC Powder, and Vick’s VapoRub. Others had no medicinal quality but tasted good. Graham crackers, Grape-Nuts, and most sodas (Pepsi Cola, Coca-Cola, 7-Up, sarsaparilla) began as patent medicines.

Patent medicines are still with us. Nutritional supplements, diet pills, and pills for “natural male enhancement” are marketed on television and the Internet. The legal loophole for each advertisement is the statement that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not tested the product nor approved it for the treatment of illnesses.

Patent medicines are still with us. Nutritional supplements, diet pills, and pills for “natural male enhancement” are marketed on television and the Internet. The legal loophole for each advertisement is the statement that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not tested the product nor approved it for the treatment of illnesses.

The exhibit, Medicine and Illness: Health Care in Geneva, is on display at the Geneva History Museum, 543 S. Main Street, through June 16, 2018.