Geneva and the Underground Railroad

(From April 1991 Historical Society Newsletter. The article has been updated to reflect current terminology).

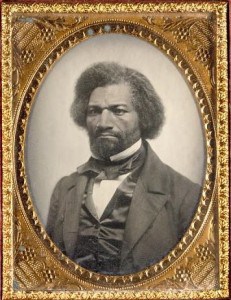

The question of whether Geneva was a “station” on the Underground Railroad has long been a subject of local debate and speculation. Because of the romance and secrecy surrounding the Underground Railroad, it is difficult to substantiate the many persons and places involved. Although there are many homes with tunnels and hidden rooms throughout Upstate New York, very few have a documented place in the history of the Underground Railroad. Key operators in the network such as Frederick Douglas in Rochester and J.W. Loguen in Syracuse constantly urged secrecy. In My Bondage and My Freedom, published in 1855, Douglas lamented:

I have never approved of the very public manner in which some of our western friends have conducted what they call the ‘Underground Railroad,’ but which I think, by their open declarations, has been made, most emphatically the ‘Upper-ground Railroad.’ Its stations are far better known to the slaveholders than to the slaves.

According to Kathryn Grover, exhibit curator for Make A Way Somehow: African-Americans in Geneva, New York, 1790-1965, the most reputable accounts on the Underground Railroad do not mention Geneva. Although Geneva was not thought to be a major route, there are accounts of freedom seekers finding safe haven here. Adelaide Prouty recorded in her diary on March 6, 1861, “two fugitives came to us and begged assistance…” In his 1963 publication, The Underground: Freedom’s Road and Other Upstate Tales, Arch Merrill claimed that Genevan Josephine Johnson had given him family records documenting that her family’s home at 20 Pulteney Steet had harbored freedom seekers. Gerrit Smith, active in the abolitionist movement and the Underground Railroad, also had strong ties to Geneva. He owned land here (now Lochland) and his son and nephew lived here before the Civil War and his daughter (Elizabeth Smith Miller) here after the war. Preserved among Smith’s extensive correspondence is a letter from Genevan Edwin Barnard, a jeweler and a Presbyterian who had converted to Congregationalism by 1837. Barnard was active in Geneva’s Sunday School Movement which offered the only education available to the village’s African Americans until they established their own school in 1841. Written by Barnard on July 30, 1852, the letter is torn around the edges and words are missing:

I learn from J.W. Duffin there has been a fresh importation of Human [torn] & that you have the care & direction of them [torn] supposing that your aim is to locate them [torn] the best advantages for themselves. [torn] two friends in Hamonds Port [torn] Co. Wim Hastings LD Hastings, both wishing [torn] domestics in their families. My object in [torn] ascertain if there are any & if they can [torn] from that quarter if would be natural [torn] that among the number (50 I learn man [torn]) there would be some that are accust [torn] and would like this employment. They are men [torn]lling to care for them & do well by them [torn]uld be glad to have an answer by return mail [torn] are here now & should be favorable [torn] one of them will come and see you.

Yours for Humanity Edwin Barnard

Despite the missing words it seems clear that Gerrit Smith had received at his Peterboro, New York home fifty freedom seekers, both male and female. Edwin Barnard’s wish was to place them in homes in upstate New York sympathetic to their situation. Although it isn’t known if any of these freedom seekers were placed in Geneva homes, at least one freedom seeker is known to have settled in Geneva – Charles Peyton Lucas. Lucas, who changed his name to Charles Bentley, appeared in the 1850 Geneva village census and on the list of disenfranchised black Genevans that James W. Duffin recommended to Gerrit Smith in 1847 for land grants. Lucas/Bentley moved to Canada after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850 and within five years had written a brief account of escape from slavery. Although the high level of abolitionist activity in the region and the settlement of freedom seekers in Geneva does not prove the existence of local Underground Railroad stations, there were Genevans sympathetic to plight of freedom seekers.

Update – Historic Geneva staff has still not found evidence of Underground Railroad stations in Geneva.