150th Anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation

Lincoln and his cabinet at the first reading of the Emancipation Proclamation, July 1862. U.S. Senate Collection.

A little over one-hundred fifty years ago, on September 22, 1862, President Lincoln took a step he had planned for months and proclaimed that as of January 1, 1863 “all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.…” This marks a watershed moment in our nation’s history, when the country began a long march toward practicing the ideals that are enshrined in our Declaration of Independence. The importance of the Proclamation is undeniable even though it did not actually free anyone. It only applied to the slaves in the Confederate States, which were not under federal control. Yet, it marked a realization on Lincoln’s part that the Union could not be preserved with slavery intact and that emancipation was essential to winning the war.

The proclamation was welcomed by the enslaved, free blacks, and abolitionists. The Republican Geneva Courier gave full support to the President’s announcement. The editors had supported abolition at least since October 1855, when the newspaper’s masthead began sporting the motto: “No More Compromises With Slavery—No More Slave Territory—No More Slave States.” The Proclamation incensed Confederates and Union Democrats. The Democratic Geneva Gazette suggested that Lincoln’s move was unconstitutional and that he had given in to pressure from the radicals in his party. The editors believed “there has been no such staggering blow against the fabric of our Union since the outbreak of the rebellion.… It will swell the ranks of the rebellion…it [will] dishearten if not to paralyze the efforts of our devoted Union army….” The Irish working class was a major component of the Democratic Party in New York and Gazette articles also played on their fears of losing jobs to black workers. A notice that a Philadelphia hotel had fired all of its white workers and hired black workers was concluded with: “Thus it is that Emancipation is coming home to the doors of the ‘poor whites.’ Hereafter we will have it—‘no whites need apply.’

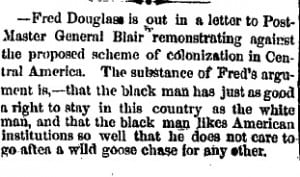

It is difficult to overstate white Americans’ inability or unwillingness to imagine a way for millions of formerly enslaved black people to live freely in “their” country. Lincoln was actively considering ways to have freed slaves colonize land in the Caribbean, South America or Africa (see this blog by scholar Phil Magness). Even many abolitionists simply could not imagine a world in which freed slaves could live peacefully among their former masters. Some, including Lincoln, feared the freed people would be subject to violent reprisals, others thought they would take vengeance on their former masters, still others thought they were incapable of supporting a democratic society. State Assemblyman Albert Andrus, who “despise[d] the institution of slavery,” could also state in 1862, “For surely no one could think of turning this black population loose upon the whites of the South, nor does any one wish them sent among us at the North.” He looked for God to deliver the nation from the slaves, “then may these States live together in peace and harmony, as one great family…”

A speech by New York Assemblyman Gilbert Dean reprinted in the February 27, 1863 Gazette is typical of the racist opinions most white Americans had: “[Soldiers]…have hearts and brains; and if you tell them that this war is to be perverted from the object for which it was undertaken, that it is now to be prosecuted for the purpose of making eleven States…a jungle like those of Africa…. I ask you to make enquiry of the returned volunteer…—ask him if you could induce him to go into this war for the extermination of the white men of the South, and the enthroning there a negro [sic] power. …[P]rogress is with our race—while the African is necessarily dependent, and that never has the negro race been capable of supporting a civil government.”

What is undocumented, however, is what the African-American community in Geneva thought about the Emancipation Proclamation, though we can assume that like Frederick Douglass, they would “shout for joy that we live to record this righteous decree.” Perhaps like Douglass and many abolitionists, the local black community recognized the significance of this move, which according to Lincoln, transformed the war into a war “of subjugation” in which “The South is to be destroyed and replaced by new propositions and ideas.”

In the end, the North won the war, and this is what happened. Unfortunately, the nation did not truly fulfill the promise of emancipation until the African-American community stepped forward in the 20th century to demand its fulfillment. On this year’s 150th anniversary of the Proclamation, we are still dealing with the legacy of slavery in the United States and searching for ways to move closer to the promise “that all men are created equal.”