Early Schools of Geneva

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

The recent debates over Geneva’s school budget and national arguments about the Common Core curriculum have had me thinking and reading a lot about the history of education this past spring. Education and schooling have been part of life in Geneva from its early settlement, though not in a form most modern Genevans would recognize. Dutch colonists provided schools for children from the early years of their settlement, but under the English, New York did very little to support elementary public schooling. This did not change much in the first decades of statehood. Instead, the government’s focus was on chartering secondary schools (academies) and colleges. Beginning in 1784, these secondary schools were administered by the Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York. Elementary, or common schools (for the common people), were generally private schools in the state’s early history. In 1787, the Regents reported, that they “feel themselves bound…to add that the erecting [of] Public Schools for teaching reading, writing and arithmetic is an object of very great importance which ought not to be left to the discretion of private men but promoted by public authority.” They continued to advocate for the establishment of a common school system, until the Legislature finally passed an act for “the encouragement of schools” in 1795. This law provided an appropriation of 20,000 pounds per year for five years for the encouragement and maintenance of common schools. The appropriation expired in 1800, but five years later the Legislature used revenue from land sales to create a permanent fund for state support of schools.

Although non-Native settlement of Geneva began by 1786, it is unlikely any formal schools existed prior to the creation of the town of Seneca (later divided into the towns of Seneca and Geneva) in 1793. The following year, developer Charles Williamson, interested in drawing eastern residents to settle in the community, set aside a lot for the construction of a school building on property currently occupied by the session room of the Presbyterian Church. A school was built on the lot, and the first known teacher was a William H. Gunning, who placed the following notice in the 1797 Ontario Gazette:

“The subscriber for the last time requests those who are in arrears for schooling in 1794 and 1796 immediately discharge their accounts…”

This school probably began as a privately funded school, and Mr. Gunning had to collect his pay from the families whose children attended it. For it was not until May 1796 that the town residents elected school commissioners and created Geneva’s first public school district. The commissioners could receive money from the state’s Common School Fund and may have contributed to Mr. Gunning’s wages for the school on Pulteney Park, but it is unclear if this was the case. In 1798, the Pulteney Park property was transferred to the newly formed Geneva Academy Association and became the home of the Geneva Academy, the forerunner of Hobart College. Academies were entitled to Common School funding for any pupils who studied “only reading, writing, and common arithmetic.” Again, whether the Academy functioned as the de facto public school is unclear from the evidence available. Williamson then granted the school district another lot on Pulteney Street, just west of Trinity Church for a new common school. This may have become the location of the district’s public school building, but again, there are no records to verify this.

A permanent law organizing the common schools was finally passed in 1812. This law established a statewide school district system under the management of an appointed Superintendent of Common Schools. The law separated the common schools from other educational institutions that were supervised by the Regents. It also authorized the distribution of interest from the Common School Fund established in 1805. According to this law, each town was to elect three commissioners of schools who would be responsible for dividing the town into school districts and distributing the state money among them. The freeholders (white male property owners) in the district would then elect three school district trustees and three inspectors. The inspectors visited and inspected the schools and teacher. The trustees would be charged with hiring instructors and paying them out of public funds. The taxpayers could also approve a local tax to fund schools if the state funds were insufficient, which they generally were. In addition, fees, or rates, could be charged to the parents of students in the school if additional revenue was needed.

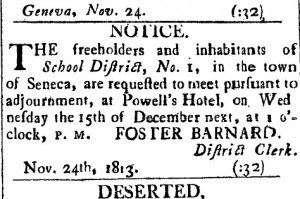

As the Town of Seneca had already established districts under the 1795 law, the commissioners met on November 11, 1813 to alter them based on the new law, and invited “those who feel themselves aggrieved by the present arrangement” to attend. A month later, the inhabitants of District No. 1 met at the Geneva Hotel to vote on taxes and school trustees. Districts were also established within the year at Billsboro and on farmland owned by the Ansley family. Eventually there would be eight district schools formed within today’s Town of Geneva, including two in the village itself. District No. 19 was centered at the school on Pulteney Street. A brick school house was constructed there in 1822, and pupils could attend for “6 shillings per quarter.” A second district, No. 1, built a brick building on Geneva Street the same year. For the next twenty years, these two schools and a smattering of private schools provided education to Geneva’s children.

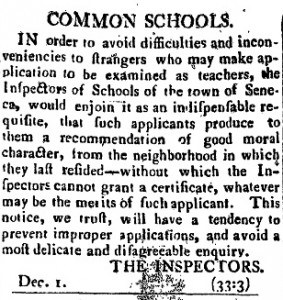

Teachers in these early schools were normally male and the education rudimentary. State Superintendent Gideon Hawley wrote in 1813 that common schools were to be “nurseries of useful knowledge, they are designed to fit youth for active life, and useful avocations; ornamental accomplishments are to be sought elsewhere.” This meant reading, writing and arithmetic, along with basic geography and history. Hawley recommended that potential teachers be evaluated equally for their moral character as for their learning. He should be a strong Christian, “regular in his habits, exemplary in his morals, patient under trouble, slow to anger, persevering in purpose and decisive in action.” In reality, teachers were often poorly qualified, sometimes educated little more than their students. Perhaps because pay was so low, well-educated men did not pursue it for long unless they started their own schools. According to an account of the schools in East Bloomfield during the 1820s and 1830s, male teachers were paid $12 to $18 per month. They taught in the winter, when older and often disruptive farm boys attended school. Women were preferred for the summer months when only girls and children too young to work attended school. The female teachers were paid one-third to one-half what the men made and also taught embroidery and needlework.

Reflections; or Sentences and Moral Maxims by Francois Duc De La Rochefoucauld and The Juvenile Philosopher were books on morals and science used in early American schools.

Attendance was a problem early in the century. In 1838, a committee investigated attendance at the village schools and reported to the Geneva Gazette that the village’s 10 private and 2 public schools educated a total of 349 children between 5 and 16 years of age. As there were 876 children of that age living in the village, they concluded that 527, or more than half, did not attend school. They estimated that one-third were working and could not attend. About 40 to 50 were “colored” children. Apparently that was enough of an explanation, as schools were usually segregated in New York at this time, and the village had not chosen to fund a separate school for children of the state’s former slaves (that is a blog post for a future time!). These considerations aside, they determined that some 300 children were not being educated who ought to be attending school. The committee thought that many of the problems of village education would be resolved by consolidating the two districts and building a large and modern school. The transformation of the village schools into one district is where we will continue our story next time.

For more on early educational history in Geneva and New York State, see the following:

Aldrich, Lewis and George Conover. History of Ontario County.

Horner, Harlan Hoyt. Education in New York State, 1784-1954.

Related Posts

Founding of the Geneva School District

Segregated Schools in Geneva’s Past

Very much appreciated reading this information…would enjoy hearing about the transformation of the village schools into one district…how the public schools developed in particular.

Also, I have a silly question…regarding the pastime of croquet on the lawn at Rose Hill…wondering how they mowed their lawn so nicely back in the day before we had power mowers? I suppose they may have had sheep, but what did folks living in town with lawns do?

Thanks again,

Nancy

Nancy,

Glad you enjoyed it. I will return to the topic in the spring after a short sojourn to the 1960s, as there is a lot more to tell.

Regarding Rose Hill’s lawn, I don’t know if we have any particular evidence about the Swans (who did have sheep), but mechanical lawn mowers were invented in England in 1830. American mowers were being produced after the Civil War, so they would have been available to the Swans at the time of our croquet photo of about 1876.

I recently came across a reference to “Geneva School District Papers 1797-1801”. I’m hoping to use those to identify some of my ancestors there during that period. Do you have any idea who might have these? Ontario Records and Archive says they don’t have them.

I don’t know what those might be. I will have to check with our archivist who is out of the office on leave for a while. It is my understanding that nearly all of the records from Ontario County schools were unfortunately disposed of 25 years ago, so there is no official record of that sort. Where did you find the reference? In writing this post, most of the information specific to Geneva came from the newspapers published at the time, a history of the school district printed on its 100th anniversary in 1939 and secondary sources like Conover’s History of Ontario County and Lucile Harford’s Country Cousin.