Free Schools for Geneva

Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

During the 19th century, the United States developed most of the basic features of the free public schools system that we still have today. This resulted in school enrollment in the young nation that exceeded that of any other nation in the world by 1850. One of the important features was schools open to any child in the community. These were well established in Geneva by the 1820s, as described in our first and second blog posts on the city’s schools. The founders of the nation emphasized public education as essential to the republic’s future and as a protection against tyranny. A second feature of American education that developed during the middle of the century was public funding of education for all children.

Educational institutions, public and private, have a long and important history in Geneva. We saw in our last post on schools how the growth of the village in the 1820s and 1830s led to the creation of a new unified school district in 1839. Instruction became centralized at the Union School on Milton Street, which served children in the community from age four up. Despite an expansion to the structure in 1842, the building soon became overcrowded due to further population growth and because more parents were sending their children to school.

In 1852, the school district trustees recommended adding a wing onto the Union School, selling the site of the segregated school for black children, and building three new branch schools for younger children. They also moved to request that the state designate the Union School as an academy qualified to teach classical subjects and receive money from the Regents Literature Fund. Roughly equivalent to the modern high school, the Union School would prepare young men for college and clerical jobs and scholars of both sexes for teaching positions. Voters approved construction in April of 1853. New schools were built on Jackson, Cortland, Lewis and High Streets, with the High Street School designated as the “colored school.”

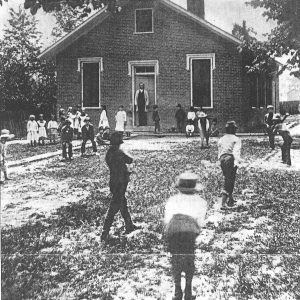

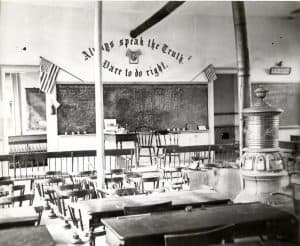

Based on descriptions and photographs of the 1870s, each of the branch schools was a simple brick building that held up to 120 children, although the attendance reported in the newspaper was between 40 and 70. The branch schools served children from four years up to age twelve or thirteen and provided a basic education in reading, writing and arithmetic. The schools consisted of one large room divided by a center aisle with rows of benches, chairs or desks on either side. One side of the room was for boys and the other for girls. Photos from the 1870s show a second small room, which may have been both a coat room and a space for instruction. The buildings were heated by pot-bellied stoves in the center of the large room. At least two of the schools had outdoor water pumps by the 1870s, but the High Street school relied on a nearby creek for water into the 1880s. Privies were located behind the buildings. The schools generally seem to have had two teachers, though the High Street and sometimes the Jackson Street Schools were reported as having only one. Most teachers were women, all unmarried. Those children that performed well in the branch schools could continue on to the Union School, though most did not.

This was a period of great debate about the role of education in American society. Dislocations and changes in large cities prompted efforts at education reform. In the early 1800s, cities like New York and Boston were grappling with growing populations of people from diverse backgrounds. Problems of poverty, crime, juvenile delinquency, and labor strife exploded as the social controls which worked in small rural communities proved inadequate in the new urban environments. Reformers had diverse views, but generally saw publicly funded and organized schools systems as an important solution to the problems caused by urbanization. They believed that well run schools available freely to all residents would teach children—especially immigrants—republican values, prevent distribution of public funds to sectarian (Catholic) schools, and decrease crime and vice. They were also the first to argue that education was preparation for the workforce and that free publicly supported schools were a right of the state’s children.

As the Geneva expansion indicates, parents were increasingly interested in education for their children. Public schools were growing in size and attendance. As explained in our previous post, schools at the time were funded from three sources: state funds, local property taxes and fees paid by parents of students. In New York and many states, public support of schools meant that taxes paid for the construction and fuel costs for a school house, as well as the cost of educating the poor. Some money was also provided by the state for teachers’ wages, books and equipment. If the state and local funds were not enough to cover the cost of the teacher, parents were billed for the difference, with indigent families exempted. Rates of tuition listed in the newspaper in 1855 were 1 ¼ cents per day for the branch schools and 2 cents per day for the Union School (parents only paid for the days their children were actually there). Therefore, school ran about 25 cents and 40 cents per month per child for the schools. This seems relatively affordable, given Robert Swan’s farm workers in Seneca County were paid about $10 a month in the same decade. Artisans, clerks and businessmen would have earned more.

The first statewide call for free schools came in 1844. In 1849 the legislature passed a law that required schools to provide a tax-supported free common school education to all children. Although approved by state voters that November, resistance to the law was very strong, particularly in rural areas. Due to the public opposition, the legislature repealed the act, putting the repeal to a vote in November of 1850.

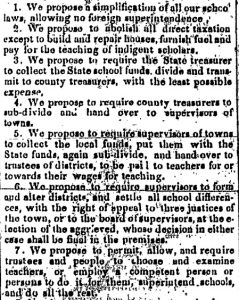

Just prior to the repeal vote, the Geneva Gazette published excerpts from a pamphlet attacking the Free School system. Objections to the law focused on the constitutionality of taxing one man to educate another man’s children. Rural areas also vehemently opposed the state exerting any control over local schools, including requirements for teacher training or inspection, arguing:

“It is a poor commentary upon our school system, having now been in operation about forty years, if we have not in every school district, men competent to judge of the qualifications of their schoolmaster; if [the teachers] are incompetent, their young children will find out in a few days if their master is a fool and tell their parents of it.”

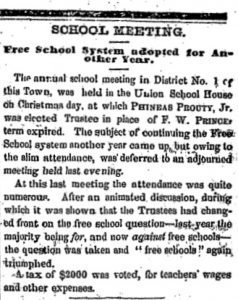

Although the state-wide effort to enshrine public education into law failed in 1850, more and more state school districts chose to dispense with the rate bills as their communities grew more supportive of free public schools. Free school systems had already been established in major urban areas by 1853, including New York City, Buffalo, Syracuse, Rochester and Utica. The Geneva school trustees continued to rely on rate bills until the school meeting of January 1858. At this time the trustees announced that they would raise the local funds for the coming school year entirely through taxation, “making tuition free for all.” The Gazette noted, “We are thus up to the liberal standard adopted and in vogue by many towns about us, in providing for the free education of our youth.” Interestingly, at the end of the year a majority of the trustees wanted to discontinue the free schooling, but “after an animated discussion…the question was taken and ‘free schools’ again triumphed.”

It was not until 1867 that the state legislature abolished the rate bills, increasing the state property tax to fund the change. By this date, most districts were already committed to free public schools and the law was uncontroversial. In 1894 the state fully committed to the right of its children to an education by writing it into that year’s revision of the state constitution.

This system served Geneva and much of the state well for the next forty years, until the movement for compulsory education and the expansion of high school education in the 20th century.

Sources:

Goldin, Claudia and Lawrence Katz. The “Virtues” of the Past: Education in the First Hundred Years of the New Republic. Working paper. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2003. Retrieved online at http://www.nber.org/papers/w9958.

Fraser, James. Report on the Common School System of the United States and Upper and Lower Canada. 1866. Retrieved from Google Books.

Randall, S.S. History of the Common School System of the State of New York From its Origins in 1795 to the Present Time. New York and Chicago: Ivison, Blakeman, Taylor & Co., 1871. Retrieved from Google Books.

Related Posts

Founding of the Geneva School District

Segregated Schools in Geneva’s Past