The Community Response to the (Geneva) Princeton Plan

By Becky Chapin, Archivist

The original proposed Modified Princeton Plan to Geneva would house first, second, and third grades at Prospect and kindergarten, fourth, and fifth grades at North St, with Prospect Ave kindergarteners continuing to attend West St. Within weeks, the plan changed to create the North-Prospect and West-High complexes.

After reviewing the first plan, The Interschool Committee passed this resolution:

Whereas the problems deriving from failure in education in racially unbalanced schools are national in scope and importance but local in origin, and; Whereas the continuing racial unbalance in Geneva’s elementary schools contributes to the perpetuation of the total national problem; Therefore, since both overcrowding and racial unbalance are critical problems in our school system; Be it resolved that the Board of Education be urged to move with all dispatch to consideration of the Princeton Plan or an alternative similar in principal to end racial imbalance and overcrowding in our schools.

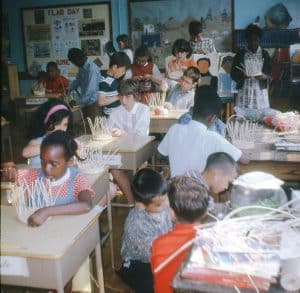

Recently digitized, our slide collection holds numerous class photos from High St, West St, North St, and Prospect Ave Schools. This small sample shows the racial imbalance in the elementary schools. A sixth grade class at High St.

Genevans were incredibly attached to their neighborhood schools. The first group to publicize their displeasure was the North Street Home and School Association (HAS). It felt that the plan singled out only North Street and Prospect Ave schools.

Other meeting attendees did not like that students would be transferred in general. An attendee denied that a ghetto existed in Geneva with others agreeing.[1] Other members of the HSA thought the problem was based on housing and was economic in nature so the pressure of using schoolchildren to solve deeply rooted issues was not the solution. Unfortunately for these members, the state was requiring school districts to come up with a solution for any racial imbalance.

A group called the Citizens Committee for Fair and Equal Education was formed in August 1968 to oppose the compulsory transportation of any student, preserve and improve the high-quality education in neighborhood schools, and support practical means of expanding quality integrated education for all children without violating the basic rights and freedoms of anyone. The committee required a fee to join which would inhibit those without the economic means to pay.

Soon, the committee had circulated a petition objecting to the plan, gaining over 800 signatures. Their goal was to sue the Board of Education and school district to seek an injunction to stop the implementation of the modified Princeton Plan. In filing a legal case, the committee hoped to compel the Board to close Prospect Ave due to its inadequacies and halt the implementation of the plan in order to create a new plan that would encompass the entire school district. One of their suggested solutions was to transfer half of the non-white children from Prospect-North to West-High. However, as pointed out by the school board president, this would not be treating all children equally.

They rightly pointed out that the modified plan didn’t fully solve the racial-cultural imbalance problem in the district with a 7% population at West-High and a 24% non-white population between North-Prospect in 1967 (at Prospect that number was 57.9%). Additionally, the inadequate facilities at Prospect Ave School would downgrade the educational opportunities of all elementary children in the north Geneva area.

While the committee did sue the Board and school district, they weren’t able to prevent the plan’s implementation before the new school year started. They followed through with the lawsuit but were denied the injunction in December 1968 since the plan was already in effect and it would be a greater hardship on the children. The committee continued their legal action into 1969, seeking a permanent injunction in March.

Three committee members ran for the school board in May 1969, though none were elected, and by June a Rochester court upheld the school board’s modified plan. The committee continued its work, requesting in 1970 a state education commissioner investigate the board, superintendent, and administrative policies because requests for information related to enrollment and racial distribution were denied.

Meanwhile, on a state and national level, antibusing bills were coming up in the legislation that would impose a moratorium on the compulsory busing of schoolchildren to address racial imbalance. Other studies debate whether busing stimulated white flight from public schools to the suburbs or private schools. A white exodus leaves fewer and poorer white people in urban areas for integration.

A year after its implementation, Geneva teachers were interviewed for their thoughts on the modified Princeton Plan results. Most of the questions were for the Prospect Ave teachers.

- Do you feel the learning atmosphere is better for the former Prospect pupils now that they attend the North-Prospect complex? 12- yes, 0- no

- Do you think the attitude of the former Prospect pupils toward school and learning is better than it was last year? 11- yes, 1 no, 1 same

- Do you prefer teaching in an integrated classroom? 12-yes, 1- either

- Do you feel that the children who attended Prospect last year are holding back your group? 1- yes, 20, no

- Do you think that the children in the North-Prospect complex are getting along with each other? 24- yes, 0- no

- Can you see improvement in language development in the pupils who attended Prospect last year? 7- yes, 3- no, 3- same

Most comments from the teachers felt that a judgment couldn’t be made on the success of the program after eight months. One teacher addressed a difficulty with staffing at Prospect Ave which was helped by the plan’s implementation. Another teacher was quoted: “Discipline and classroom management have improved which contributes to improvement in most academic areas.”

Letters to the editor on the topic of the modified Princeton Plan were frequent and fraught in the late 1960s and early 1970s. One letter addressed the continued issues with Prospect Ave School and its inadequacies, and quoted the superintendent who said High Street was the “worst school in the state.” Another addressed the issues of overcrowding in the North-Prospect complex that was made worse by the plan. While addressing the school building program in 1968, another letter pointed out that one of the suggested options would have been implementing the full Princeton Plan anyway. (See the options in my last blog article)

The modified plan was spoken about at various club meetings in town. An Irondequoit school board member speaking to the Kiwanis Club claimed schools were taking on both the job of education and solving the ills of society. A local doctor speaking at the Geneva Country Club liked the neighborhood school system but saw the merits of the full Princeton Plan and believed the whole community had the right to participate.

The League of Women Voters 1980 school study concluded the board should be encouraged to achieve racial equity in the schools, and this goal continued to be included in their focus on local programs for many years.

By the time, the Geneva Education Advisory Committee offered their plan in 1982, problems regarding testing results between West and North Street Schools were brought into focus. The study concurred with the League that West Street School students scored higher on achievement tests than students at North Street School. The superintendent believed this was influenced more by socio-economic issues rather than any racial imbalance, suggesting that there was a clear boundary line in Geneva between the more affluent and less affluent populations.

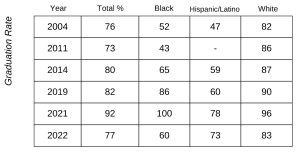

The overall dip in graduation rates post-2020 is an interesting dataset. This could be an effect of the COVID-19 pandemic disruption. This table does not include all ethnicities reported.

The advisory committee’s 1982 plan to correct the gap in test results included extra help for students at North Street, changing district boundaries, and reorganizing the elementary schools on a K-2 and 3-5 basis. This plan, they felt, would standardize the curriculum between schools, foster the same learning environment for all children, and distribute those children considered to be educationally disadvantaged. But as was said in my last blog, the school district couldn’t justify the costs.

Since the school district was reconfigured in 2009, statistics show an graduation rates among non-white students have increased between 2010 and 2019. This has likely been impacted by local agencies such as Success for Geneva’s Children (est. 1997) and Geneva 2020 (now Geneva 2030) who are working to intervene in early literacy and support students K-12 outside the school.

[1] Historically, a ghetto is defined as a quarter of a city in which members of a minority group live especially because of social, legal, or economic pressure. I’ve discussed housing segregation in Geneva in the past and would disagree with this attendee.