Segregated Schools in Geneva’s Past

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

We often think of the historic struggle to gain racial equality as the fight to defeat legal segregation in the South. In reality, this struggle went on in every community in which African Americans have lived and worked, including Geneva. Recent discussions about race reveal the continued difficulty Americans have grappling with this aspect of our history.

Documenting the struggle for racial equality in the 1800s can be very difficult. Historic records of the time include government records, newspapers, diaries, land transactions, burial records, photographs, and artifacts. Because of their historically precarious economic and social position, as well as lower rates of literacy, African Americans are often underrepresented in or absent from the historic record. In addition, institutions such as museums, libraries, and archives have not always sought, welcomed, or saved the material history of the African-American community. Where they are documented, African Americans are usually viewed from a white perspective, a perspective that is often remote and invariably biased.

Fortunately for Geneva, much of the African-American community’s history is recorded in Kathryn Grover’s 1994 book Make A Way Somehow, which grew out of the Geneva Historical Society exhibit of the same name. The following information is drawn largely from that book and the sources Grover cites in it.

To this day, a flash point for racial conflict is education. Matters were little different in the 19th century. Many Americans are familiar with the segregated schools of the Jim Crow South, however, officially segregated schools existed in most 19th-century communities in the North, including Geneva. It took the concerted efforts of Geneva’s African-American community to advocate for improved education and eventual integrated schools for their children. Ante-bellum New York did not have laws requiring separate schools, but the state allowed them by default if the white majority in a community objected to integrated schools. As a result, almost all districts with an African-American population had segregated schools.

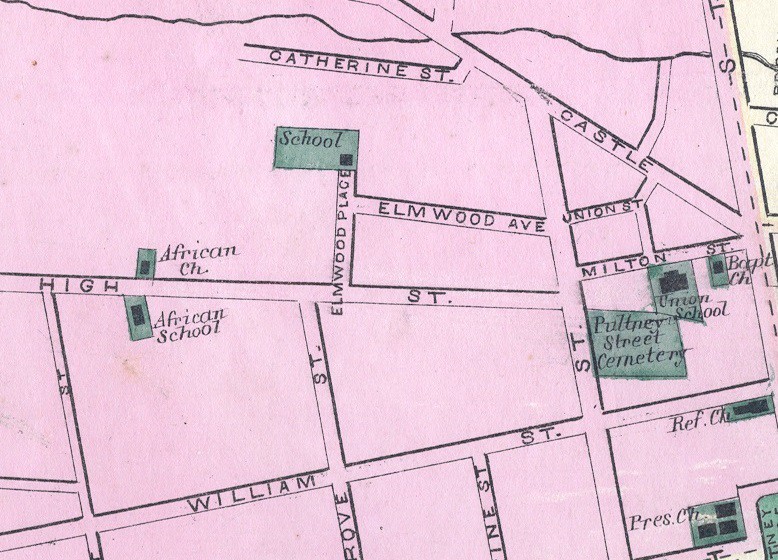

Constructed about 1834, this church building on High Street was home to Geneva’s first African-American school.

Although Geneva opened its first public school in 1796, the earliest recorded formal schooling for African Americans was Bible instruction at the Episcopal and Presbyterian Churches beginning in 1816. Believing that education was the best hope for bettering their economic condition, most African Americans strove to acquire some education for themselves and their children. In 1830s Rochester, they petitioned for separate schools: “We do humbly believe that…our children might be encouraged to learn: and although they are black, they may be made comely members of society.” The petitioners stated their preference for a separate school since their “children are despised, called Negroes, and completely discouraged by the white children” in the public schools (petition quoted in Rochester Historical Society Publications, Volume XVII). The state supported separate education, legislating in 1841 that “Colored children are entitled equally with all others, to the privileges and advantages of the district school: and wherever they can be grouped together in a separate school…they will be far more likely to derive the full benefits of such instruction as may be best adapted to their circumstances and condition, while at the same time, the disadvantages inseparable from their attendance at the district school, will be avoided.”

Geneva’s African American community had started their own school in the late 1820s, as their children were not welcome at the district schools. It was begun as a Sabbath School at the African-American Union Chapel on High Street. In an 1837 report, the Ontario County school superintendent listed seventy-two students in attendance at the church. The school became well known in anti-slavery circles when the controversial black abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet served as its superintendent and teacher from 1849 to 1851. Frederick Douglass’s North Star reported on an exhibition by Garnet’s students in 1849, stating that the presentation “effect[ed] a revolution in the minds of those preconceived against the colored man’s capacity for improvement.” The revolution was short lived, for white villagers were at best indifferent to African-American education during the ante-bellum years. Even the construction of a school building required intense effort on the part of Geneva’s African-American citizens. They petitioned the district to construct a school house in 1841, but it was not until the 1853 creation of the branch school system, that the district built a “colored school” on High Street.

There are few records of this school, beyond its construction. It was built and furnished at a total cost of $1113, while the other branch schools built in 1853 cost $1600 each, plus $400 for furnishings. By the post-Civil War era it appears to have been a grossly inadequate facility. The Geneva Gazette [the newspaper of the pro-South Democratic Party] proclaimed the teacher was “thoroughly competent” in 1871, yet in the same piece indicated that he could not instruct languages as teachers at the other schools did. In the same year, the African-American Ontario Debating Club argued the assertion “colored schools are a disgrace to all concerned in them.”

Further evidence of the school’s poor quality and the district’s hostility to advanced study by African-American students appears in an editorial printed in the Geneva Courier [the Republican paper] in 1870. The article details the discrimination experienced by two High Street students who tried to enter the Classical and Union School. According to the author, the boys were required to take a Regents examination for admission, while white children were admitted without an examination. This was despite a resolution adopted at the December 31, 1869 School Meeting “That any scholar from any branch school shall be admitted to the Geneva Classical School on the same terms, without distinction of race or color.” Due to their inadequate preparation at the segregated school, the students failed the test and were told to return to the branch school.

The effort to enter the secondary school was likely motivated by the 1869 passage of the 15th Amendment barring racial discrimination. African Americans in Geneva and elsewhere took advantage of this amendment to fight for their right to equal education in the North as well as the South. In January of 1872 Albert Arnold, an African-American, made a resolution at the school board meeting “proposing to discontinue the school in High street as a separate school for the education of colored children.” The matter is continued in an editorial in the same issue of the Gazette, which reveals the determination of the African-American community:

Shall all our public schools be opened to colored children?—This question has been forced upon the attention of the people of this school district for the last three years, and although our colored population has met with adverse decisions, each defeat seems but to nerve them to increased persistency in pressing their claims to equal recognition with the whites in the premises.

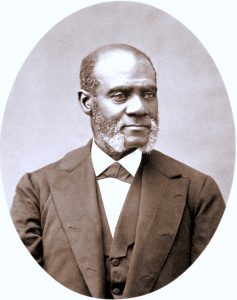

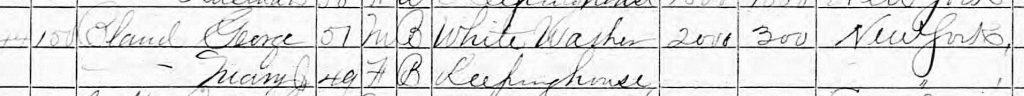

This tenacity eventually prevailed. In early 1873, New York State passed a Civil Rights Act barring school segregation. In April of that year the Gazette reported “For the first time in the history of the Geneva Common Schools, those in charge of such institutions…were compelled to admit colored pupils and seat them in with white children…” Despite these achievements, it was some time before the Classical and Union School admitted any African-American students. In May of 1873 a letter published in both Geneva papers decried the continued discrimination against African Americans attempting to enter the school after two more students were examined for admission and failed the examination. The Courier responded: “It is impossible that the prejudice of education and ignorance should be out-grown in a moment,” while the Gazette writes characteristically “the Gazette has no sympathy with the colored folks or their white sympathizers who seek to force children of the former into our public schools in association with whites.” At a celebration of the Civil Rights Act the following August, George Bland told of “his fruitless efforts to obtain admission to the Union Classical School of this village for the children of his race.”

George and Mary Bland owned property on West Street near High along with about a dozen other African-American families in the mid-1800s.

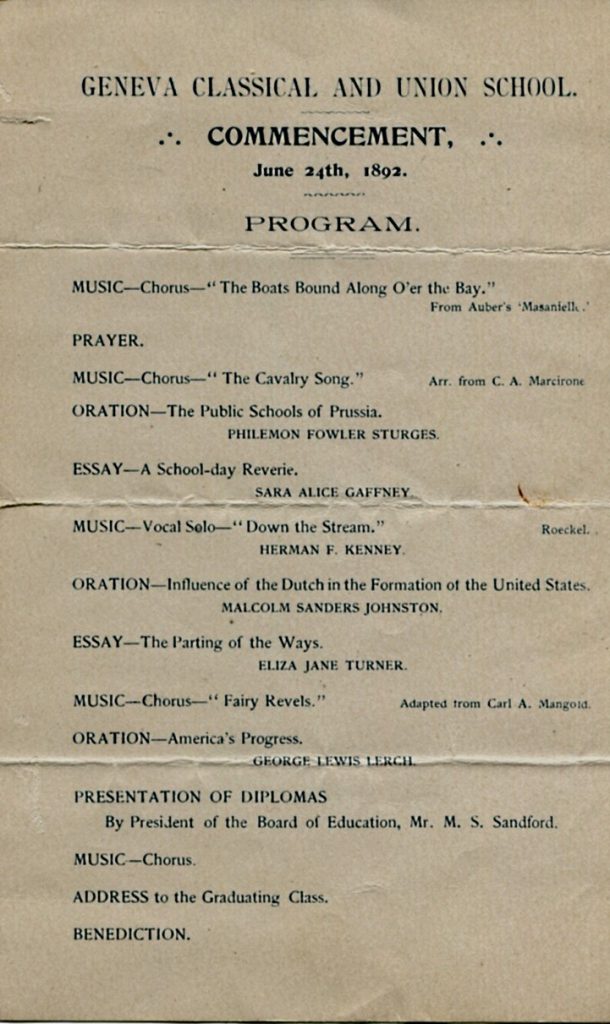

After 1873, the subject of segregated schools in Geneva was dropped from the newspaper. There is no record to indicate when the first African-American student was admitted to the Classical and Union School. Herman F. Kenny is listed in the school’s 1892 commencement program, and is the earliest documented African-American to graduate from the school. By the turn of the century a few African-American students attended the high school each year. The issue of segregated schools would not appear in the Geneva press again until the Civil Rights Movement and the modified Princeton Plan threw the Geneva community into turmoil in the 1960s.

African-American Herman F. Kenney was a featured soloist at the 1892 Classical and Union School commencement.

Related Posts

Founding of the Geneva School District

The (Geneva) Princeton Plan: 56 Years Later

The Community Response to the (Geneva) Princeton Plan