Deaf Artist Francis Tuttle

By Alice Askins, Education Coordinator at Rose Hill Mansion

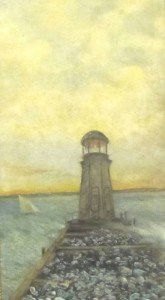

Francis Marion Tuttle was a Geneva artist who lived from 1839 to 1911. He was well known for Seneca Lake views and portraits, and he also did some Biblical scenes. Instead of repeating Tuttle’s his biography (for his biography visit dianrez.blogspot.com), I want to focus on one part of his life, namely, that he was deaf. His experiences bring up some interesting issues.

Francis Marion Tuttle was a Geneva artist who lived from 1839 to 1911. He was well known for Seneca Lake views and portraits, and he also did some Biblical scenes. Instead of repeating Tuttle’s his biography (for his biography visit dianrez.blogspot.com), I want to focus on one part of his life, namely, that he was deaf. His experiences bring up some interesting issues.

Tuttle was educated in New York City, and had many contacts within the deaf community. He was a kind man, as shown by the report in the Daily Gazette of August 16, 1872:

A Kindness. – On Wednesday afternoon of last week the Infant Class of the M. E. Sunday School, numbering about 70, held their annual pic-nic [sic] on the lake shore . . . Mr. F. M. TUTTLE, who has a fine fleet of boats, generously gave all the little folks a ‘row’ on the lake, much to their pleasure and delight.

Yet this gifted, nice man was often in the paper for unfortunate reasons. The first sign of trouble I found was from July 1881. The Advertiser reported,

Our deaf mute artist, Mr. F. M. Tuttle, has had four narrow escapes with the railroad trains this summer. His residence is on the hillside, south Main street, and in crossing the track to his boat house, has jumped from the track when the locomotive has been within ten feet of him. Only his keen sense of feeling has preserved him from a casualty.

Those incidents did not end his list of narrow escapes. At least seven times between 1891 and 1904, the papers noted that Tuttle had been nearly or actually run down by bicycles, tricycles, street cars, and horses and wagons, because he could not hear them coming. Based on the accounts, the collisions had happened many more times, and Tuttle sustained some painful injuries. “The wheelman could have avoided it,” said the Advertiser [June 18, 1895.] “There is no question but he is entitled to the sidewalk” [February 4 1896.] Naturally, Tuttle was frustrated – “He says he will not stand another collision, but will break the first wheel [bicycle] that runs him down.” [February 4,1896] “He wants to know why teams cannot be driven less rapidly past his home.” [January 1, 1901] “. . . he would soon like to know whether or not he has any right on the street.” [Advertiser-Gazette April 1, 1902] In fact, Tuttle was more fortunate than one of his friends, also deaf, who was killed by a street car in Syracuse in 1906.

It surprised me that after the first incident, Tuttle did not take the utmost care crossing streets and trolley tracks. Perhaps, he tended to be distracted, thinking about his next painting. It surprised me even more that the cyclists and drivers were not being more careful of pedestrians. I looked briefly into the history of traffic regulation, and there were relatively few traffic laws enacted before the turn of the 20th century. The popularity of bicycles in the 1890s created new crowding problems on roads. Though there was some regulation in response to demands by cyclists, it was more to establish cyclists’ right to the road, than to protect pedestrians.

Though pedestrian right of way seems to have been an unexpressed concept, I still don’t understand why anyone would approach a pedestrian at a high rate of speed, blandly expecting him to get out of the way. Some people cannot move quickly. Some might be deaf. Some might be intent on their own thoughts.

Leaving that issue aside, Tuttle had other troubles:

Advertiser August 16, 1881

M. Tuttle suffers the loss of his “duck” sail boat, taken from its moorings at a very early hour this morning. It may have been borrowed for a pleasure ride, but Mr. Tuttle’s mind would have been easier if the person who “borrowed” it had considerately asked for it.

Advertiser June 3, 1884

Notice to Boys. – Mr. F. M. Tuttle desires us to say that last summer in the bathing season several fish poles and lines, a silver spoon hook, a heavy anchor and other things were stolen from his boat house. He will not permit bathing at his boat house this year, and will prosecute all boys who trespass upon those grounds day or night. There is plenty of room at the pier for bathing .

Daily Gazette July 12, 1889

Who Stole the Oars?

Somebody entered F. M. Tuttle’s boathouse recently and stole a fine pair of oars. Mr. Tuttle would like to interview the chap in the “sign language” (bunches of fives) for about two York minutes. The thief would think he had encountered John L. Sullivan [a famous boxer.]

Advertiser September 24, 1889

M. Tuttle has politely given cards to all the boys who have been in the habit of stealing fruit from his trees, to the effect that he has no fruit to spare, and that they will oblige him by leaving it alone in future. Surely they ought to heed such politeness and kindness. If not, they must take what follows.

Daily Times December 26, 1895

The artist F. M. Tuttle reports . . . that . . . while [he was] on his way to Mr. Coursey’s office . . . some one [sic] threw a stone at him, and [he] thinks there are bad boys who should be looked after.

Over the past few years, I have looked through the newspapers for everything I could find about a lot of people. Never have I found anyone else who suffered this kind of petty theft and harassment. The Advertiser assumed that it was because Tuttle was deaf.

Mr. F. M. Tuttle . . . complains that a lot of boys down on State street and the streets adjoining have been pelting him with stones. Boys, it is a great misfortune to be deaf . . . It is much more pleasant to assist a blind man, or one who is deaf . . . than to annoy them in any way. We hope the parents of those boys will take them in hand; if not, perhaps the court will help Mr. Tuttle out.

We know the 1800s and early 1900s as a period when people were trying to reform the world. There was no named movement that I am aware of to persuade people to be kinder to each other, but there seems to have been an informal one. I happened across several bits of persuasion printed in the local papers over time.

Courier August 22, 1855

You were made to be kind, and generous . . . If there is a boy in the school who has a club foot, don’t let him know that you ever saw it. If there is a poor boy with ragged clothes, don’t talk about rags when he is in hearing. If there is a lame boy, assign him some part of the game that does not require running. If there is a hungry one, give him part of your dinner. . . .

Daily Gazette March 14, 1884 (a poem addressed to boys)

Never taunt the wretched outcast,

Be he helpless, lame or blind.

Some of the 1855 advice was repeated in 1896 and attributed to Horace Mann. The Daily Gazette went on, though, to quote the Ithaca Democrat:

April 03, 1896,

. . . there is a great need at present of a compulsory law to teach children courtesy, and the personal and property rights of individuals.

We might, then, consider that the Victorians had a reform movement urging human kindness. And, I think we are still working on that one.

So perhaps we should not assume troublesome youth are a modern phenomena?

Lots of nasty boys already in those years.

Mr. Tuttle seems to be a quite wealthy man and I have read some place that the present Cobblestone restaurant was a beer hall and owned by a Mr. Tuttle.