Celebrating African-American Freedom

African Americans have celebrated American freedoms since well before the nation recognized their right to share in those freedoms. The earliest of these celebrations were a form of political protest, as former slaves in the “free” North gathered, usually in August, to protest their exclusion from the rights other Americans celebrated on Independence Day. These festivities started after Great Britain freed her slaves in the West Indies. The Emancipation Celebrations later incorporated other advances in black civil rights, including the emancipation of American slaves, the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, and the passage of various Civil Rights bills and laws. Today Juneteenth is the most well-known of these festivals, celebrating the date during the Civil War when enslaved African Americans in Texas learned of their emancipation.

Emancipation celebrations were a vital part of Geneva’s African-American history in the 1800s, beginning in 1840 and continuing intermittently until the 1890s. Geneva’s first known African Americans, Cuffe and his wife Bett, were brought to the shore of Seneca Lake (at Rose Hill) in 1792 by Alexander Coventry. During the next decade, the Rose and Nicholas families moved from Virginia, bringing over 100 more enslaved African Americans to the area surrounding Geneva. These people formed the nucleus of a vital and persistent African-American community. Over the next fifty years this population grew, augmented by the migration of former slaves from the farms of Wayne, Ontario, and Seneca counties and by fugitives from the South. With a population of 639 African Americans, Ontario County had the largest black population of any county in western New York by 1860.

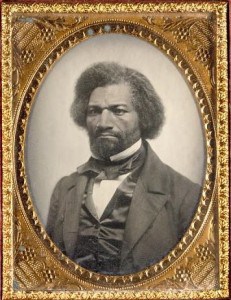

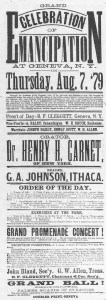

Western New York Emancipation Celebrations moved from town to town and were hosted by Canandaigua, Auburn, and Penn Yan and other area communities. Its central location and sizeable African-American population made Geneva a favorite spot for these events, and the village hosted at least eight in the 19th century. Local political officials were sometimes invited to attend the festivities and march in parades to Pulteney Park or Genesee Park. In the parks or halls, members of Geneva’s African-American community read important documents from their crusade for freedom: the act by which England had freed West Indians, the Emancipation Proclamation, the 15th Amendment, and the New York State Civil Rights Bill. Luminaries like Frederick Douglass, Henry Highland Garnet, and Sojourner Truth spoke to crowds of people from Geneva, Rochester, Syracuse, Auburn, Lyons, and the surrounding region. Many of the celebrations included prayer, parades, songs, sports competitions, food, and an evening dance.

Unfortunately for historians, most existing accounts of these celebrations are filtered through biased white perceptions. In her 1994 book Make a Way Somehow: African-American Life in a Northern Community, 1790-1965, historian Kathryn Grover teases out the possible meaning of these Geneva celebrations for the African-American community. Using reports from national sources like The North Star and the biased commentary in Geneva’s white papers, she argues that the celebrations were political demonstrations, which white residents often chose to view as harmless theater or purely social events.

Frederick Douglass spoke at many of Geneva’s Emancipation Celebrations. Daguerreotype portrait from the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian.

When they reported on the celebrations, the local papers invariably concentrated on the amusements and social aspects of the festivities, rather than the political content that underpinned the gatherings. At the 1860 celebration held in Geneva, Frederick Douglass gave his first address since returning from Europe, where he had fled after the arrest of John Brown, whom he called “the hero of Harper’s Ferry.” He spoke of the example of the British in freeing their slaves in the West Indies and his disappointment that the United States, with its proclamations of liberty, continued to support slavery and the slave trade. He addressed an audience that understood him when he said,

I have spoken and written much on the subject [of slavery] during the last twenty years, and have been at times accused of exaggeration; and yet I can say with truth, that I have fallen far short in describing the pains and woes…. The warp and woof of slavery is yet to be unraveled.—Each bloody thread must yet be disentangled and drawn forth, before men will thoroughly understand and duly hate the enormity, or properly abhor its upholders and work its abolition. This is the work still to be done. After all the books, pamphlets and periodicals—after all the labors of the Abolitionists at home and abroad—we have still to make the American people acquainted with the sin and crime of our slave system.

Rather than focus on Douglass’ arguments, the Geneva Gazette newspaper emphasized Douglass’ “free ebullition and bile in his criticism of churches, political parties and society generally.”

After the Civil War and Emancipation, Geneva newspapers devoted more space to celebrations that seem to have lost their political force. At the same time that white southerners were terrorizing African Americans in the post-Reconstruction South, the 1881 orator Frederick Stuart never mentioned it. He focused on the long history of African-Americans in the country, their contrast to the Chinese immigrant laborer, and the importance of black labor in places “where the white man cannot—in the warmest parts of the country,” in the cotton fields, sugar plantations and iron foundries. He pointed out that black Americans paid taxes and that progress that had been made in education. At the same time, he reminded his audience (white and black) that “We are…just as much within the circle of American citizenship as if we had come over in a different manner [than as a captive]. The negro belongs here.” The writer went on to detail the subsequent social events with no acknowledgment that this citizenship was being denied across the country. One of the last celebrations in 1900, “hardly came up to those of former years” in attendance. The audience was described as mostly white and attracted by the sporting events. The decline of the Emancipation Celebration occurred as many African Americans left Geneva and other small towns in the late 19th and early 20th centuries for the opportunities available in larger cities. The local community seems to have become too small and too focused on survival to host large celebrations. This remained the case until the post-World War II era.

For more information about these celebrations and about Geneva’s African-American community, see the 1994 book Make a Way Somehow: African-American Life in a Northern Community, 1790-1965 by Kathryn Grover.

I am so pleased to read this history on Geneva, NY as well as other cities in that area of upstate NY. My maternal family hails from Geneva, Auburn, and Seneca Falls, from as far back as 1850. I hope to soon be coming to the area to learn more about my families there during those times and to speak to natives and historians who can help fill me in on what life was like there back then. Thanks for all the information so far. Much loved!

Could you please educate us as to how many, and of what faith traditions in Geneva of African Americans?

trying to understand the religous landscape .. know of presbytery. dioceses and Provinces… where, beyond the historic church… did the 19th century did African Americans worship

I am working at home and don’t have my copy of Make a Way Somehow with me. Kathryn Grover devotes an entire chapter to the subject of African-American churches. From what I recall, the first enslaved people shared the Episcopal denomination with their masters, the Roses. I don’t think they were permitted to attend services, although my memory is not clear on this. Early on there was a satellite church for African-Americans called St. Phillip’s Mission that met in the basement of Trinity Church. It was not long, however, until segregation drove many of Geneva’s African Americans to start their own churches. In the 1800s, there were several mainline denominations with African-American churches. It was not until the migration of new families from the South after WWII that most of today’s black churches in Geneva were founded. You can read about one in this blog post about Mount Olive Missionary Baptist Church.

Thank you, Anne for a very informative article. Do you by any chance know where the early African Americans were buried? Did they have their own cemetery?

Maryrose,

I am not aware of a segregated cemetery, but that doesn’t mean there wasn’t one. There may be more specific information in our archive, but there are several early African-American graves in Washington Street Cemetery. Some members of the Bland family (including the John Bland named in the poster above) and the Duffin family are interred at Washington Street. There may be some burials at Pulteney-in-Glenwood as well, though I don’t know that cemetery as well and don’t have the resources at home to check on it.

Anne, I have an 1818 manumission record from Seneca Co., NY for a slave named Thomas van Wagener. I found a Thomas “Wagner” enumerated as a black man from the 1830 through the 1850 census for the town of Seneca, Ontario Co., NY. I didn’t find an Underground Railroad study for Ontario County as Judith Wellman did in Seneca and other nearby counties. Would you have any suggestions on how I might proceed though I know records other than census may be scarce on Thomas van Wagener (Wagner).

Kate,

That’s very interesting. I am going to send your request on to our Archivist Becky Chapin, as she may have more information for you than I do. I do not believe a study has been done for Ontario County, but I am not sure about that. Good luck!

Mrs. Dealy,

Perhaps you can put me on the right path. I am looking for the story of Roxanna Binks (Binx) (born circa 1789). She was the mother of William Binks who married Rebeca Binks (Gillam). They had a daughter named Ida who married Daniel Coleman and then had my Great Grandmother Florence who married a Jacque. The lived in Geneva until my Great Grandfather died in 1932 then moved Rochester. Roxanna and William pop on the scene before the 1850 Census in Ontario. My assumption is that they worked at the hotel but have no way to show that. I am also looking for the burial place for Roxy or William Binks. Was Rebecca related to Philip Gillam and how did he get his freedom? Any record of that?

I don’t know the answers to your questions but will pass them on to our Archivist, Becky Chapin, who may be able to direct you. Given the size of the Geneva community of African Americans in the 1800s, it is very likely the Gillams are related.

I am the great grandson of Ida and Daniel Coleman, if you’d like to reach out please do.

Gary.jr.coleman@gmail.com

My name is margaret Edna Mathews I am the great granddaughter of margaret her mother was ida. I would love to learn more.

Ms. Dealy,

I am pleased to find your articles and blog. My interest is two-fold. One is learn about the race relations history of Geneva, my birth place (1951), and of nearby Phelps where I grew up. For example, was Phelps ever a sun down town? Certainly I only encountered one African American child in school and then not even for a full semester.

The other question concerns the name Gillam I see in Patrick Frazier’s letter above. My wife of 6 years is a Gillam through her late mother, of Norfolk VA. We would be interested in finding a connection if any.

Thank you

I am glad you enjoyed the article. If you want more background on Geneva’s African-American community, we have a number of other posts on individuals and institutions in the city. Just click the tag African Americans to see a list. You should also read the book Make Away Somehow linked above for a general history of Geneva’s African-American community through 1965. We are currently working to extend that research as you can read here. As far as Phelps, I am afraid I do not know anything about an African-American community there. I did find a short piece here and you might follow up with the Phelps Community Historical Society to find out more. As for the Gillam connection, I checked with our archivist and the Gillams we have been able to trace in Geneva seem to have been descended from an enslaved man brought here by James Rees, an agent of the Pulteney Estate who came from Philadelphia. Finding your wife’s family might require some digging through genealogy materials to see if there is a connection. An good place to start is familysearch.org. Good luck and happy searching!