“Any New and Useful Improvement”

By John Marks, Curator

Researching a new exhibit always turn up fun things I didn’t know. Geneva Innovators will open Saturday June 12, but work on it began a few years ago. In 2019 Becky Chapin created posters about Geneva inventors and patent holders for an archives fair in Rochester.

I knew little about patents before now, except they seemed to be a stamp of authority. The right to claim an invention as one’s own was written into the Constitution in Article 1, section 8:

“The Congress shall have Power … To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

The Patent Act of 1790 created a board of patent commissioners to personally inspect applications to see if they were original and “sufficiently useful and important.” The commissioners were three men: the Secretary of State, the Secretary of War, and the Attorney General. These men were busy with their own jobs and weren’t fully qualified to judge what deserved a patent.

The Patent Act of 1793 fixed the situation. It removed the commissioners and the words “sufficiently useful and important.” It defined a patented item as, “any new and useful art, machine, manufacture or composition of matter and any new and useful improvement on any art, machine, manufacture or composition of matter.”

This brings us to research on Geneva patent holders. Decades ago, someone typed up index cards of local people who obtained a patent, with the date and patent number. Armed with this information, I went to the US Patent & Trademark Office website and began searching for patent drawings and applications.

This brings us to research on Geneva patent holders. Decades ago, someone typed up index cards of local people who obtained a patent, with the date and patent number. Armed with this information, I went to the US Patent & Trademark Office website and began searching for patent drawings and applications.

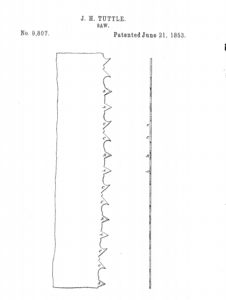

In 1853 Joseph Tuttle invented a sawtooth pattern for cutting across the wood grain. Alternating teeth (B & C) scored the sides of the cut and pulled out the sawdust to prevent clogging. The “Tuttle tooth” pattern for crosscut saws is still used today.

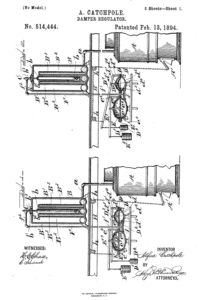

Some inventions were complicated and required more explanation of their uniqueness. In 1894 Alfred Catchpole designed a damper regulator for steam boilers. Two big issues for boilers were automatically regulating pressure, and air flow to the furnace, so this was a significant device.

Some inventions were complicated and required more explanation of their uniqueness. In 1894 Alfred Catchpole designed a damper regulator for steam boilers. Two big issues for boilers were automatically regulating pressure, and air flow to the furnace, so this was a significant device.

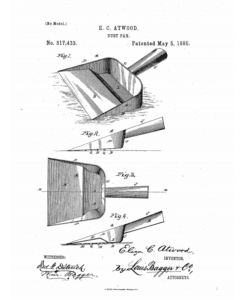

Eliza Atwood was an example of patenting a “useful improvement” to something as mundane as a dustpan. She added graduated teeth on the base to keep the pan from sliding, and a lower section to collect dust. The 1885 application said, “The recess or receptacle I at the rear end will served to retain the dust after being swept into the pan, thereby avoiding the common disadvantage of the dust being spilled after being once swept up.”

Eliza Atwood was an example of patenting a “useful improvement” to something as mundane as a dustpan. She added graduated teeth on the base to keep the pan from sliding, and a lower section to collect dust. The 1885 application said, “The recess or receptacle I at the rear end will served to retain the dust after being swept into the pan, thereby avoiding the common disadvantage of the dust being spilled after being once swept up.”

These are just three examples of Geneva patents before 1900. A complete list up to today would probably fill a small book. Another research project is to find which inventions made it to production and for how long.

Geneva Innovators will open Saturday June 12 at the Geneva History Museum, 543 South Main Street, and be on display through April 2022.