Geneva’s “Busted Yankees”

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

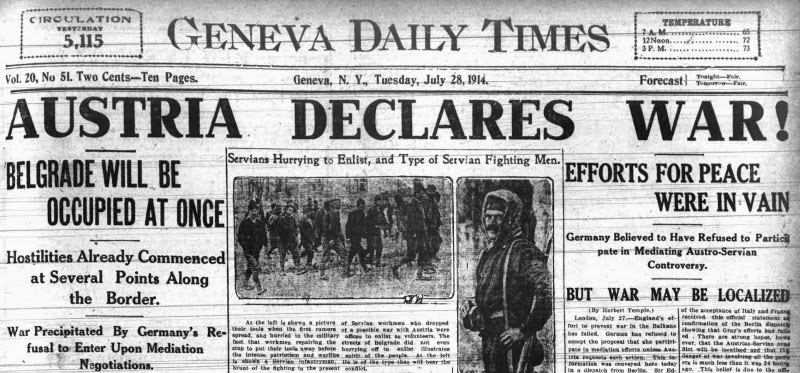

Austria was the first nation to declare a state of war. They were quickly followed by Russia, France and Britain.

World War I exploded across the pages of Geneva’s newspaper during late summer, 1914. The front page of the Geneva Daily Times abruptly shifted its coverage from the Mexican Revolution and civil unrest in Haiti and Ireland to full-blown coverage of the war in Europe.

One immediate U.S. concern was for Americans abroad. As we saw in our previous post about the Herendeen family, the war came about so suddenly and unexpectedly that few people were prepared for it. As mobilization for war began across Europe, there were over 100,000 Americans visiting or living abroad who were unable to leave easily. In addition to covering the national story of these “busted Yankees” as they were sometimes called, the Geneva Times reported on local citizens who were caught up in the start of war and their efforts to return to Geneva.

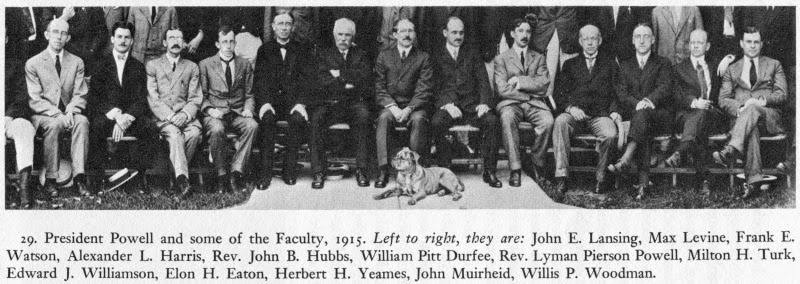

In an August 1 article about Americans abroad, the Times listed 22 Genevans known to be living or traveling in Europe. Many were professors or scientists associated with Hobart and William Smith Colleges or the State Agricultural Experiment Station, while others, like the Herendeens, were touring the continent. One couple was on their honeymoon trip.

When the war began on August 4, the United States pledged to remain neutral, so Americans were not in any particular danger in the nations they were traveling in. However, no one wanted to be in a potential war zone, and the rush was on to get back to the States. There were two main problems facing those who wanted to leave: money and transportation.

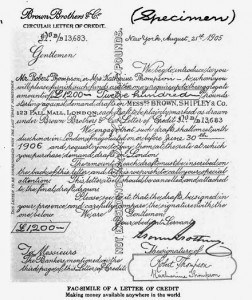

As we saw in John’s previous post, Frank Herendeen was in no rush to leave Germany. He and his family could afford to stay in the country during mobilization. Other Americans were not so lucky. Travelers at this time relied on cash, traveler’s checks or letters of credit drawn against funds deposited with a bank or broker based in the United States. In the first days of the war, many European banks would not honor checks or letters of credit, and travelers soon began to run out of money. The U.S. State Department had to act as an intermediary, helping those in the States send funds to their relatives in Europe. By August 4, Congress had appropriated $2.5 million dollars to be distributed to Americans stranded in Europe without money. On August 11 the Times reported that American diplomats were trying to get 5,000 penniless students out of Germany.

Transportation was the second problem, largely due to war mobilization. On August 4, a Geneva resident and native of Germany, Joseph Holz, explained to the Times how German mobilization worked. He said that his male relations were probably already with their regiments. The order for mobilization of the army immediately put the nation under martial law, subjecting all transportation and communication lines to military control. News of the order for mobilization was spread by telegraph, telephone, courier, and paper bulletin. Response was immediate:

Every man drops his work as soon as he hears the order; the plow is left in the furrow; customers are left at the counter; balances are left unchecked in the bank. Every man liable for military service rushes to the nearest transportation line, which will take him to his regiment, whether its headquarters be a mile away or 100 or 500 miles distant. The reservists do not wait to pack luggage or food. There are clothing, equipment and food for all at the mobilization centers in storage warehouses, always filled, ready for the call. Men go to the trains often hatless and coatless.

According to Holz, this drill was practiced twice a year. German reservists did not need train tickets, since only soldiers could ride the trains during mobilization and they rode for free. This was one reason many foreigners had difficulty getting out of Europe, and why Herendeen did not rush to leave. Trains simply weren’t running for civilians until after the armed forces were assembled, which took about two weeks. Passenger trains were evidently commandeered in other countries as well. American travelers got out however they could, crammed into freight cars and cattle cars with makeshift benches, or like Genevan Katherine Gracey, sitting on a suitcase in the aisle for two days.

Getting news in Geneva of stranded relatives was also difficult. During mobilization the government took control of the telegraph lines and private messages were difficult to send. In addition, shortly after the war started, the British cut all five German telegraph lines passing through the English Channel. Most families had no news of their relatives for two weeks or more. The Times reported every letter and cable from a Genevan that came to their attention. Katherine Gracey, who was in Switzerland when war broke out, was able to cable her safety to her family by August 13, but a letter she sent on July 31 was not received until August 24. Her family did not hear from her again until she cabled from London on September 4.

Hobart Professors Alexander L. Harris and Edward J. Williamson were among those Genevans caught in Europe during the outbreak of war.

Some Americans were concerned about being mistaken for British subjects. This was a legitimate problem as passports were not required for travel in most of Europe and therefore not all travelers had them. The situation became a dangerous one for the head of the HWS German Department, Professor Williamson, who was trapped in Berlin at the outbreak of war. Canadian-born, he had a British passport and was in danger as soon as Britain declared war on Germany. Citizens of enemy nations were not permitted to leave the country, and he had to appeal to the American Embassy for a passport. The passport was granted based on his long residency in Geneva, and he was able to leave on a train especially for Americans. He was lucky, or he could have been one of the more than 5,000 British civilian men interned in Germany during the war.*

Those who had been in Austria, Switzerland, France and Germany made their way slowly to ports in Holland, France and Italy, where they hoped to get steamship passage back to England or the United States. Then the difficulty became finding and paying for passage. At the same time that scores of people were fleeing Europe, ships were canceling runs across the Atlantic. As soon as war broke out, German and Russian steamships ceased running to the U.S. for fear of capture. Like the trains, many ships were also requisitioned for troop transport. The U.S. government even ordered battleships to Europe to assist in bringing Americans home. Katherine Gracey traveled across the English Channel from Havre to London on the Tennessee, which had left Virginia on August 6 with $8,000,000 in gold bullion to help Americans stranded in Europe. It shuttled them across the Channel and then went to help Jewish refugees leave Palestine as the war engulfed the Ottoman Empire.

USS Tennessee transports expelled Russian Jews from Palestine to Alexandria, Egypt, c. 1914. U.S. Naval Historical Center

The least lucky travelers may have been the few immigrants to the United States who were back visiting family or friends in Europe that summer. According to Geneva’s newspaper, one of these, Geneva Cutlery grinder Frederick Schneider of Avenue B, was in danger of being drafted into the German army. There seems to be no further reference to him in the paper, and he is not listed in the city directory after 1913. He may well have been shipped to the Front.

All other travelers accounted for in the Geneva Daily Times appear to have returned from their adventures unscathed. Some reported their ships sailing with lights extinguished at night or being stopped by British or French ships on their way out of European waters. A few heard rumors of their ships being followed, but none reported any great concern for traveling. Americans in far fewer numbers would continue to cross the Atlantic, a voyage that would become very dangerous by January 1915 when Germans began to sink American merchant ships. The German sinking of the British passenger liner the Lusitania in May of 1915 resulted in 1000 deaths, including 128 Americans. This incident and the sinking of American ships became a source of anger that would turn American opinion against the Germans by 1917 and lead the United States to join the European conflict.

The 1915 sinking of the Lusitania helped turn American opinion against Germany. Courtesy German Bundesarchiv.

*Both the Germans and the British had internment camps for POWs and men of fighting age caught behind their borders at the start of war. See the sites below for more on this forgotten history.

Ruhleben Internment Camp

http://www.prisonersofwar1914-1918documents.com/