Slavery at Rose Hill

By Kerry Lippincott, Executive Director

Bett, Cuff, Aggy Gaten, Aunt Dinah, Aunt Judy Gaten, Berlet Kenney, Billy Nicholas, Bristol, Ceaser Gaten, Charles Kenney, Dangerfield Lee, David Kenney, David Lee, Edmond Lee, Emily Douglas, Garrett Kenney, George Gaton, Godfrey Gaten, Henly Douglas, Henry Douglas, Henry Gaten, Jenny Kenney, John Gaten, John Kenney, Lucy Nicholas, Margaret Douglas, Maria/Mary Gaten, Nancy Kenney, Peter Lincoln, Phillis Kenney, and Tom Gaten.

To the best of our knowledge these were the enslaved people who lived and worked at Rose Hill between 1792 and 1827. While more research is needed, the following is what we currently know about slavery at Rose Hill.

Westward expansion is tied to slavery at Rose Hill. Rose Hill stands on the traditional, unceded lands of the Gayogo̱hó:nǫ’ or “the People of the Great Swamp.” In English, they are known as the Cayuga Nation. In 1779 the Sullivan-Clinton Campaign destroyed numerous Cayuga and other Haudenosaunee villages and burned acres of fields and orchards. The destruction weakened the Haudenosaunee and forced them out of the area. This led to European expansion into Western New York. The northern tip of Seneca Lake served as the border between two tracts of land the Military Tract and Genesee Country.

In 1782 the New York State Legislature set aside land for Revolutionary War veterans. Known as the Military Tract, 1.8 million acres of land was set aside between Lake Ontario, Seneca Lake, and present-day Onondaga County. Today, that area would be the present-day counties of Onondaga, Cortland, Cayuga, and Seneca, and parts of Oswego, Tomkins, Schuyler, and Wayne Counties. The land was surveyed into 28 townships that were divided into one hundred lots. Each lot had six hundred acres. The land, however, still belonged to the Haudenosaunee and New York State had to negotiate with several Nations to purchase land within the Military Tract. The property that eventually became Rose Hill included Lots 11 and 17. These lots passed through several hands before Dr. Alexander Coventry purchased them in 1792.[i]

Born and educated in Scotland, Coventry came to the United States in the fall of 1785 to take charge of family property near Hudson, New York. Upon his arrival he settled into what would be his pattern: combining agricultural pursuits with a medical practice.[ii] With the opening up of Western New York, Coventry explored the Mohawk Valley, Military Tract and Genesee Country between 1790 and 1791.[iii] Apparently, Coventry must have liked what he saw near present-day Geneva, as he purchased Lot 11 and within a year he added half of Lot 17 to his holdings.[iv] Coventry named his land Fair Hill after his childhood home in Scotland. During the spring of 1792 Coventry and his household moved from Hudson and settled in their new home. Besides Coventry the household included his wife, Elizabeth; their two daughters; hired men; and and enslaved couple. Cuff and Bett would be among the first African American settlers to the Finger Lakes.

Coventry’s journal provides some glimpse into the life of Cuffe. It appears that Cuffe negotiated some basic terms of his work. Bett was enslaved by another person and Cuff refused to move unless Dr. Coventry purchased Bett and her two youngest children, Jean and Ann. (Though he did purchase them, it does not appear the children moved here). Once Coventry re-established his medical practice and became active in the community, he relied on Cuff and his hired men for the management of Fair Hill. Their activities included planting oats, flax, corn, potatoes, wheat, and apple trees; raising cattle, horses, sheep, pigs, and chickens; tapping trees for maple syrup; hunting and fishing; and running errands. Cuff also worked for himself by raising crops, cutting wood, burning ashes, and trapping animals for fur. He was allowed to keep the money he earned.[v] Bett probably helped Elizabeth manage the household and growing Coventry family. Despite some freedoms, Coventry still owned Cuff and Bett. Coventry wrote in his journal on November 3, 1792

“Sent Cuffe over the Lake for the flour and he stayed all day. I spoke pretty sharp to him, he said he was getting his pay from Jackson for his ashes. . . . He took it so hard that I scolded him, he said he wanted another master. I told him to find a master for himself and wife and I would sell them.”[vi]

Unfortunately, the Coventry home was near the insect-infested shores of Seneca Lake, and the entire household suffered from bouts of malaria. Called “Genesee Fever,” malaria was rampant in Western New York at the turn of the nineteenth century.[vii] The only member of the household to die from “Genesee Fever” was Bette. In 1796, for the sake of his family’s health, Coventry decided to move to Deerfield near Utica, New York where again he set up a farm and a medical practice. Likely, Cuff went with him.

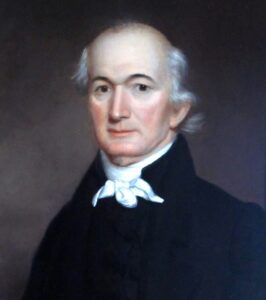

The Genesee Country’s boundaries were Pennsylvania to the south, Lake Ontario to the north, Genesee River to the west, and Seneca Lake to the east. To potential settlers in the Northeast and South land agents promoted the area as the perfect Eden: fertile soil, plentiful timber, easy transportation routes to markets, and a beautiful location.[viii] Land agents specifically set the lot sizes and prices per acre to attract a more “genteel society” and sought to secure settlers particularly from Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia.[ix] This got the attention of brothers-in-law Robert Rose and John Nicholas of Virginia. Their properties in Virginia were impoverished if not exhausted from tobacco farming. With growing families, both men were looking for a fresh start with new land. Along with information from land agents, a few family members were already settled in New York State and had good reports.[x]

Like Coventry, Rose and Nicholas must have liked what they saw when they toured the area. In October 1802, Rose and Nicholas purchased Coventry’s property along Seneca Lake (the pair would jointly own the land until 1813, when Rose became the sole owner). In addition to Coventry’s land, the pair also purchased land in present day Yates and Wayne Counties.[xi] Their plan were to grow wheat not tobacco. With land purchased, an advance party of enslaved workers was sent to clear the land, raise crops, and make other improvements. Upon their arrival, Rose claimed the Coventry property as his own, which he renamed Rose Hill, while Nicholas selected land on the other side of Seneca Lake. [xii]

At least three generations of Roses and Nicholases made the journey from Virginia to New York. This included Rose and his wife, Jane, with their three children (four more would be born in New York State); Nicholas, his wife, Anne, and their six children; Jane and Anne’s parents and aunt; and a Nicholas nephew and cousin. Seventy-five enslaved people were also brought from Virginia.

Between 1781 and 1817 the New York Legislature passed a series of laws for the gradual emancipation of enslaved people. Children born to enslaved women after July 4, 1799, were to be indentured to their former enslavers until they were 21. Enslaved people born before July 4, 1799, were granted their freedom as of July 4, 1827. The importation of enslaved people, however, was allowed into the state under an 1801 law if the enslaver came to reside permanently in the state. This could have been another attraction for Rose and Nicholas.[xiii]

Archaeological evidence shows that there were slave quarters to the north and east of the main house at Rose Hill.

Of the seventy-five enslaved people brought with the Rose-Nicholas party, thirty-seven belonged to Rose. Most of them were farm laborers who cleared the fields, built fences, prepared the land for planting, and tended the crops. There were also skilled carpenters, a nursemaid, and cook. Based on last names it appears that were several family groups and there were at least two family groups that included parents and children (Aggy and Charles Kenney with their children Berlet, Jenny and Nancy and Phillis and Henly Douglas with their children Henry, Emily and Margaret). The enslaved workers did not live in the Rose family home. There is archaeological evidence that slave quarters were constructed around the property.

There is evidence that Rose’s treatment of enslaved people could be harsh. In 1809, a Republican newspaper who opposed Rose’s candidacy for Congress portrayed him as a harsh master who shot and wounded a slave for refusing to work on Sunday.[xiv] A grandson of Peter Lincoln, a slave born in Virginia in 1771 who was part of the Rose-Nicholas migration, recorded the following story: “On one occasion a man was sent for Peter’s cradle. Peter refused to let it go. Sent for by his owner and asked why he refused, he said because he was held responsible for his tools. His master struck him with his cane at this answer and Peter said he should not do it again as he was going to leave. His master said, ‘Go and I will give you a new hat in the bargain.’”[xv]

Between 1810 and 1820, twenty-eight of the thirty-seven enslaved people at Rose Hill were freed, and there were several reasons for this. A larger enslaved workforce was only needed to get the new farm up and running. In addition to tending to wheat, cattle and sheep were raised at Rose Hill. Tending cereal crops and animals required a smaller workforce than raising tobacco. It was also cheaper to hire seasonal workers than to have a year-round enslaved workforce. As Rose became more active in politics, he rented out all but a hundred acres of his land. With time, a much smaller workforce for farming and domestic chores was needed at Rose Hill.

Born into slavery in 1812 at Rose Hill, Henry Douglas worked as a cart man, and farm overseer in Waterloo. His mother (Phillis Kenney) and sisters (Emily and Margaret) worked as domestic servants in Geneva.

By 1827, all the enslaved people at Rose Hill were freed. According to the 1830 Census, the Rose household had three people of color, most likely they were domestic servants, while the Henly Douglas family lived on the property, perhaps as tenant farmers. The Douglas family included two people under the age of thirty-six, four people between the ages of ten and twenty, and six children under the age of ten.[xvi] Though it appears some former enslaved workers stayed at Rose Hill, this wasn’t, always the case. Those who did remain in the area became the foundation of Geneva’s African American community. Tom and Godfrey Galen were freed in 1822, and their descendants lived in Geneva until the 1880s. The Kenney family may have been quite large. Between 1815 and 1816, Charles, along with his wife and three children, and John Kenney were freed. There was also Garrett Kenney, but his manumission papers have not survived. Kenney descendants significantly impacted Geneva’s history and still live in Geneva today.[xvii]

Footnotes

[i] Walter Gable, “The Military Tract” (7-The-Military-Tract-ADA.pdf), 1–3; Anne Lorraine Welling, “Rose Hill, Greek Revival Country Seat: A Study of the Forces that Shaped,” Master’s Thesis (University of Delaware, 1969), 5–6; and James A. Delle and Kristen R. Fellows, “A Plantation Transplanted: An Archeological Investigations of Piedmont-Style Salve Quarters at Rose Hill, Geneva, New York” (Northeast Historical Archaeology Vol. 41, Article 4, 2012), 51.

[ii] Welling, 12.

[iii] Welling, 12 and Diedrich Willers, Centennial Historical Sketch of the Town of Fayette, Seneca County, New York (Geneva, NY: Press of W.F. Humphrey, 1900), 22–3.

[iv] Welling, 15.

[v] Judy Wellman, Discovering the Underground Railroad, Abolitionism and African American Life in Seneca County, New York, 1820–1880 (Fulton, NY: FTS Inc., 2006), 94.

[vi] Alexander Coventry, Memoirs of an Emigrant: The Journal of Alexander Coventry, MD in Scotland, the United States, and Canada During the Period 1783–1831, Volume 1 (Prepared by the Albany Institute of History and Art and the New York State Library, 1978), 649.

[vii] Delle and Fellows, 53.

[viii] Welling, 31.

[ix] Kathryn Grover, Make a Way Somehow: African American Life in a Northern Community,1790–1965 (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1990), 13.

[x] Geneva Daily Times, September 19, 1941.

[xi] Verne Marshall, The Roses of Geneva (Interlaken, NY: Windswept Press, 1993), 10 and 14–15.

[xii] Marshall, 12 and 15.

[xiii] Grover, 18–9 and Welling, 33.

[xiv] Geneva Gazette, November 5, 1828.

[xv] George S. Conover., editor, History of Ontario County, Part II (Syracuse, NY: Mason & Co. Publishers, 1893), 107.

[xvi] Delle and Fellows, 56.

[xvii] Grover, 22.

Kerry, I appreciated your extensive research. It was very interesting reading. Thanks!

What an enlightening article! From the early history of our region’s settling to the actual realities and individuals of Rose Hill this a true gem. I feel blessed to know descendants of those early enslaved people of Rose Hill!

I understand there was also use of slave labor in building Esperanza mansion and the current Yates Cellars?

That we cannot tell you as we do not know a lot about Esperanza’s history other than the completion date of 1838. That is after 1827 when New York State required the release of all enslaved people in the state. Those held by the Roses were released at that time. Strictly on that basis, the answer would seem to be no. Of course, the wealth accumulated by the slave system did provide John Nicholas Rose the wealth to make the construction possible. You could reach out to the Yates County Historical and Genealogical Society to see if they have more information. Their website is yatespast.org. There is also some research here by a blogger wrestling with this question.

I did research and I am a decadent of John Kenny, later John McKinney