Early Geneva Playgrounds

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

The playground of today is the republic of tomorrow. If you want twenty years hence a nation of strong, efficient men and women, a nation in which there shall be justice and square dealing, work it out today with the boys and girls on the playground.

Lee Hamner, 1910, “Health and Playgrounds”

Most Americans have memories of childhood playgrounds. For decades, Americans have considered playgrounds as essential to childhood. Nearly every school and park have a playground, but this was not always the case. In the mid-1800s, schools in Geneva had yards for recess, but no equipment or structures for play. Children played games like baseball, tag, or snap the whip in the yard around the school. When they weren’t at school, they played in their own yards, if they had one. Many children played in the street and risked being run over by vehicle traffic. In some cities, playing in the street was illegal due to the hazard to people, property, and animals. According to Geneva newspapers, local boys entertained themselves in dangerous ways. They threw one another into the lake or canal. They tried to jump on moving trains or sleighs. In one instance, several jumped from a neighboring building—forty feet up—into a window of the Smith Opera House to see shows for free.

Anyone who spends time with children knows that many will get themselves into trouble if they don’t have something to do. For most of history, children had work to do and little leisure time. By the late 1800s, many children in Europe and America had free time. Most lived in densely populated urban communities with many dangers. Unsupervised children explored the world in ways that sometimes led to destruction of property or loss of life and limb. Reformers concerned about their health and safety looked for productive ways to occupy them. They introduced new ways to structure children’s time and shape their behavior. These ideas included compulsory public schooling, kindergarten, the settlement movement, the juvenile justice system, and the playground movement.

Playgrounds originated in Europe. The first one to open in the states was a “sand garden” or sand pile in Boston in 1886. Only a few others were built because many Americans thought playgrounds were a waste of public funds. The idea did not really take hold until the early 20th century. This was when the costs of industrialization became impossible to ignore. The first reports on the accidental deaths of pedestrians included a shocking number of children killed playing in the streets. Reformers like Jacob Riis and Jane Addams became interested in creating safe public places for children to play. John Dewey argued for the importance of play in child development and learning. Like schools, playgrounds were seen as training grounds for citizenship, especially for immigrants.

In 1906, reformers created the Playground Association of America with the belief that “inasmuch as play under proper conditions is essential to the health and the physical, social, and moral wellbeing of the child, playgrounds are a necessity for all children as much as schools.” The Association advocated for public funding for playgrounds and trained playground supervisors. It consulted with communities interested in establishing playground and recreation programs.

A Giant Stride like this one from the Spalding Brothers catalog, was installed at Gulvin Park in 1909 along with teeter totters and baby swings.

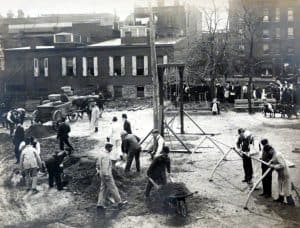

In 1900, Geneva did not have any playgrounds. The city had small parks—Pulteney and Genesee Parks and the overlook on South Main—and they were not all open to the public. Although Geneva was a small city, the community was growing at the turn of the 20th century. Citizens were concerned about places for recreation and play. A major issue was boys playing baseball. They weren’t allowed to play the game in the parks for fear they would destroy the grass or disturb the neighbors. The Geneva Times started suggesting that Geneva needed a playground. It argued the city could buy land for one, or a civic-minded citizen could donate the land. In 1905, the city bought property on Marsh Creek for the use of children in the northern part of town. However, the city took so long to develop the land that it was not the first playground in Geneva. In 1908, the Elks Club began operating a seasonal playground on the lot slated for the new City Hall. This was the community’s first genuine, if temporary, playground. Its popularity spurred the completion of the Marsh Creek Park, which it included playground equipment and a ball field by 1910. The city later named it Gulvin Park for Mayor Reuben Gulvin who worked to expand the parks. Another early Geneva playground was on land on Brook Street Joshua Maxwell willed to the city in 1914. Temporary playgrounds were also set up on the campus of Hobart College and behind the Methodist Church. The city added Jefferson and Washington Playgrounds in 1925.

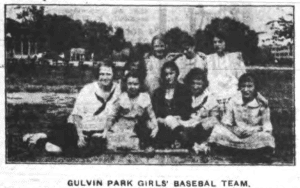

During the summer, the city hired a young college man to supervise the playground programming, especially the athletics for boys. Baseball teams for boys and girls were based at these early playgrounds. Young women supervised little children, leading them in games, storytelling, and crafts. In the winter, the playgrounds were flooded for public ice rinks. The newspaper began regular reports about activities at the playgrounds and gave attendance for the season. Attendance in the summer of 1921 was 25,000. The next year, the children at Gulvin Park planned an ice cream festival with a band concert open to the community at the playground.

By the mid-1920s the newspaper had a weekly column on the playground program. Children in the program wrote weekly letters about what they did and learned. The playgrounds competed against one another in kickball, softball, and quoits. The champions received medals at the end of the summer. Children went swimming in the lake and on picnics. The program went on even during the Depression and war years. In 1944, crafts included making model airplanes, ration book covers, and shopping bags from burlap. The playground program continued for decades, keeping generations of Geneva children out of trouble.

Do you remember Geneva’s Playground Program?

If you grew up in Geneva, did you participate in the summer playground recreation program? Where was your favorite place to play in Geneva? What memories do you have of the city’s parks and playgrounds? Did you win a kickball championship? Carve wooden animals? Make potholders? Tell us your story!

Each year, Historic Geneva plans a My Geneva is… exhibit based on community participation. This year, the exhibit theme is My Geneva is…Parks and Playgrounds. We are looking to collect photos and memories of the parks and playgrounds in the city. If you have images or memories to share, send us a photo of your chosen park or playground and share your favorite memory with us. The photo can be from any decade. Submissions will be part of the My Geneva is… exhibit and will be added to the Historic Geneva photo collection. The exhibit will open in September 2023 and run through January 2024.

Please send photos to Becky Chapin at archivist@historicgeneva.org. Call 315-789-5151 or email Becky for more information or with any questions about the project. Submissions are due August 26, 2023.

Online Sources

https://savingplaces.org/stories/how-we-came-to-play-the-history-of-playgrounds

http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Evolution_of_American_Playgrounds

https://dailyhistory.org/What_is_the_history_of_the_playground

https://infed.org/mobi/social-reform-and-organized-recreation-in-the-usa/