The Truth about General Lafayette’s Visit to Geneva

By Becky Chapin, Archivist

General Marquis de Lafayette visited Geneva on June 8, 1825. Geneva village trustees, learning he would be nearby, formed a committee who wrote a letter of invitation to him in Buffalo. Concerned the letter may miss him, two men were sent to Rochester on June 7 with a duplicate letter and the General, already going to Canandaigua, conceded to the trip.

The committee immediately made arrangements for the reception, including a few military companies of the surrounding towns. Capt. Sherman of Yates County called on his company of cavalry and they made their way to Ball’s Tavern, in Stanley, which was the designated location to meet the General. A carriage was provided by William DeZeng of Geneva to receive the General, his son, his secretary Mr. Le Vasseur, and friends Mr. Camus and Mr. Sion.

On June 8, Lafayette and his entourage met the members of the Geneva committee at Ball’s Tavern, where they changed carriages, and were escorted by Captain Sherman’s company, followed by several committee members on horseback.

All the military companies were posted near the village. When the carriages came into sight around 10 o’clock am, a signal gun was fired and all the military companies joined the line.

The citizens had gathered in the Public Square, or Pulteney Park to receive the General and his entourage. They formed two lines through which the carriage pulled up to the stage. The pavilion stage was specially built for the event and had sofas for comfort that faced a great view of the lake.

On two sides of the stage, young ladies strewed flowers and sang an ode to Lafayette written by 14 year old Miss Lummis. Behind the ladies, a very large group of people and soldiers gathered in the park. Windows of the buildings were crowded with people.

Major James Rees introduced the General and his suite to the committee members. Colonel Bowen Whiting made an address to the General and the General delivered an “appropriate Answer to the Address, expressive of his satisfaction at the kindness with which he was received by his fellow citizens in the United States, the pleasure he derived from their approbation of his public conduct- and of his ardent wishes for the continued happiness and prosperity of our country.”

The General then examined a couple of brass cannons and was escorted to Franklin House (on Exchange Street) where an elegant breakfast was prepared by its proprietor Mr. Noyes. The General talked with other veterans of the revolution. Two hundred citizens ate with him. He was introduced to many people before he left Geneva at one o’clock PM for Waterloo.

Lafayette’s visit took just a few hours. But people remember the story about Lafayette’s visit in different ways. How does that happen? People have told me they heard he had rested under the tree, known as the Lafayette Tree at the corner of Pre-Emption Road and Hamilton Street, or that he stayed in the so-called Lafayette Inn near the tree. So where have these narratives come from?

To explain the folklore around the tree, let’s look at where they could have come from.

The 1876 History of Ontario County makes no mention of a stop other than at the Geneva Hotel (in Pulteney Park). It gives a pretty brief, if somewhat fanciful, description of the few hours Lafayette was in Geneva.

The 1911 History of Ontario County claims the procession coming down Hamilton Street stopped briefly at the intersection of Pre-Emption for a signal gun to announce their arrival before the carriages proceeded on to the Park.

And here is where history starts to get murky. The author of this history, Charles Milliken, talks about Lafayette’s visit in the section biographing Charles Danford Bean. Here Bean, presumably, tells the story of how the very large tree in front of his home came to be. That in the early days of the Geneva settlement, a man called Ephraim Lee traveling through the area took a rest in a maple grove a mile west of the village, sticking his cane in the ground. When he woke up, Lee left his cane behind. He returned to the same spot a year later to find the cane had taken root and grown foliage and it continued to grow over time.

The problem with the story, besides the obvious, is that I could not find Ephraim Lee being anywhere near Geneva. He is not mentioned in any histories of the county or of Geneva. He was born in the Catskills, lived in Albany and Massachusetts but eventually immigrated to Canada where he died. Secondly, if he was in the area during the early days of the Geneva settlement as a village, which was officially 1806, the tree would not be that old by 1825. And thirdly, there is no other primary source material that I can find referring to this story. Most importantly, Milliken never mentions that Lafayette rested under the tree. He repeats the story of the military companies greeting the general, though adds ‘within a few feet of this tree,’ and that a signal gun was fired when his carriage came in sight. At the end, he says “From that memorable day this magnificent balsam poplar has been known as the Lafayette Tree.” But this is just not true.

Respected local historian George Hawley was answering a letter from a tourist writing to get more information about the tree. In that letter, Hawley says the title of Lafayette Tree was a joke as the name of the tree was the Century Tree until about 1914. In original papers from the 1825 Lafayette Committee, which Hawley had in his possession, he says the citizens were prohibited from going west on Hamilton Street, that they were meant to stay in Pulteney Park awaiting Lafayette’s arrival.

So why did Bean’s version of the Lafayette visit stick around?

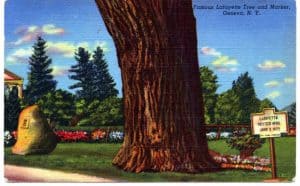

- The narrative appears on several postcards which would have spread the story further as these are kept in families or sold in yard sales and antique stores.

- The NYS Education Department installed a historic marker under the tree, at the direction of Bean, saying Lafayette stopped there on June 9th, which was the wrong date completely.

- The Seneca Chapter DAR erected a boulder next to the tree in 1922 to commemorate the visit which remains today near Tractor Supply. The plaque reads “This tree shades the spot where June 8th 1825 General Lafayette was welcomed by the children, militia, and citizens of Geneva.” City Historian and DAR member Francis Houston sought to get the marker moved to Pulteney Park in 1959. It’s revealed the DAR followed Charles Bean’s advice in putting the plaque there.

- Another marker installed by Bean was the one in front of his home on Pre-Emption Road. This marker still exists just past intersection.

A study done by a New York City botanist and by Dr. George Slate of the NYS Experiment Station in the 1940s examined a cross section of a big limb of the tree, blown from the tree in 1932, which was preserved in Hobart’s Department of Biology. They determined that in 1825 the tree would have only been about 30 years old and eight inches in diameter.

E. Thayles Emmons, a writer for the Geneva Times and author of The Story of Geneva in the 1930s, tried again in 1965 to stop the rumors about the tree. In the Geneva Daily Times for January 8, 1965, he asks “Was it entitled to the name it has borne so long? Historians, seeking facts instead of legends, say not.” Emmons reasons that at the time there was no reason to meet Lafayette at this location as it was far out in the country in relation to the then small village of Geneva. Later he remarks, “It was a legend that pleased people and was accepted.”

So why was Charles concocting all these stories? Historian George Hawley says it was to sell his house for a higher price. A member of Geneva’s upper class, Lawrence Clark claimed in a letter to City Historian Malcolm Johnston that Charles squandered his family’s money on his dream schemes (see above link).

As I’ve talked about, several city historians, and others, have done their best to counter the rumors about Lafayette having anything to do with the tree or the house since the 1930s. But publications as recent as 2022 and 2025 have shown just how far the folklore has spread.

This article was brought to you in part by our supporters. Be our partner in telling Geneva’s stories by becoming a Historic Geneva supporter.