The Prouty Family Home

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

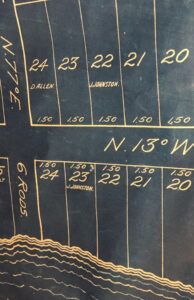

Having already examined the history of the Prouty family, now let’s look at the house they lived in for fifty years. The Prouty-Chew House is on one of the original lots laid out in Charles Williamson’s plan for Geneva. He wanted owners to build their houses on the west side of the street. The east side lots would have waterside terraced gardens, leaving an open view of the lake. In a few places, you can still see how the land from the lake to Main Street rises in gradual terraces left behind by the retreat of the glaciers at the end of the last Ice Age. Although this was a lovely idea, land is too valuable, and it did not outlast Charles Williamson.

Jacob Hallett, land agent for the Pulteney Estate, sold Water Lot 22 to Geneva businessman William DeZeng in 1815. He in turn sold it to Charles Butler in 1825. Butler was an up-and-coming lawyer working for Judge Bowen Whiting who owned the lot and house to the north. Butler married in 1825, and the new couple needed a house fitting his profession and social class. By 1829, he had built a brick Federal-style house with stepped gables and a three-bay front on the lot. In style it would have looked a lot like his employer’s house next door. Aside from the property records, we don’t know anything about the building of the house or the Butlers’ time in it.

Although a bit smaller, this house at 52 Park Place is similar to the 3-bay federal style of the Prouty house before the 1870 renovations.

The Butlers sold the house in 1836 to Francis Dwight, also a lawyer and a founder of the Geneva School District. It is unclear if he lived in the house, but he moved to Albany in 1841. He sold it to Phineas Prouty Sr. in 1842, and it remained in the Prouty family until 1902.

The Proutys, particularly Adelaide and Phineas Jr., made several changes to the house while they lived in it. We have documentation of some of these changes in their diaries and scrapbooks. Although they lived with Phineas Sr., I get the impression that they wanted to make the house their own. In 1858, they were expecting their second child and started to build a wing to the south of the house for a bedroom.

“Kit & I delighted with the prospect of having a wing to the house which will bring us downstairs. She has the whole thing planned & the exact position of every piece of furniture. Well it’s fun to talk about building even if you don’t do it but I shall try hard & do it.” Phineas Jr.’s diary, July 14, 1858.

“We have many pleasant talks of our snug bedroom & what will do – place for the children & etc. I confess too that the prospect of having a shop where I can bring together all my treasures has wonderfully delighted me.” Phineas Jr.’s diary, July 17, 1858.

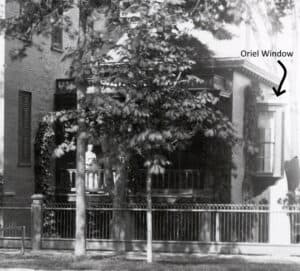

The earliest picture of the Prouty-Chew House shows the south wing added in 1858 with its oriel window.

He wanted to include an oriel window in the wing, and after some difficulty was able to get one. Oriel windows are like bay windows but are usually on upper stories. They often have corbels, brackets, or other supports underneath them. Their room was not on the second story, but due to the slope the house is built on, it was well above ground level. While there is currently an oriel window on the north side of the house, the one Phineas added to the south wing was removed in the 20th century.

He mentions adding water pipes. The house had central heating by this time, so the pipes were probably for the boiler. There is also the remnant of a speaking tube in the north wall of the room. Given all her complaints about servants, perhaps this was Adelaide’s idea. It may have connected to the basement kitchen below their wing. No evidence remains of the other end or of tubes elsewhere in the house. The wing also had a front porch that looked out on to the street. This room is currently used as our first-floor exhibit gallery.

The next major renovation of the house occurred in 1870. It seems to have been for practical and decorative reasons. By this time, Phineas Sr. had passed away, Phineas Jr. had sold the hardware store, and they had four girls from 6 to 14 years old. They may have wanted more space, but they were also creating a home in line with changing ideals. Standards for entertainment and display were becoming more elaborate for well-to-do American families. Builders’ plans for houses reinforced the division between public and private space. The 1870 renovation added space, but also transformed the public-facing parts of the building.

We don’t have any family diaries from this time, but there are diary quotes in a scrapbook in our collection. The work began on May 16, 1870, and on November 1, the Proutys sat down to eat in their new dining room (currently our gift shop). In this renovation, they added another 3-story bay to the north side of the house. This included a first-floor dining room and rooms above and below it. They had a visitors’ waiting room built to the left of the entrance (currently an office). A dumbwaiter connected the dining room to the basement (replaced by the stairs to our basement galleries). The hall, entrance, and stairway were redesigned in the popular Italianate style. This shows in the new rounded moldings, the newel post and balustrade, parquet floors, and the doors to the dining room. They installed a new front door in the double-door style found on many South Main Street houses—doors which are still visible as walls in the museum vestibule—and they added an Italianate balustrade and overhang to the front steps. They also changed the line of the roof from gabled to hipped, adding cresting along the perimeter.

- The stable and carriage house behind the Prouty-Chew House are visible in this image taken from Seneca Lake in 1896.

- Wealthy Ann Cobleigh sits on the back porch with her great-grandson Phineas Chrystie on her lap and her granddaughter Allie Prouty Chrystie and daughter Adelaide Prouty around her.

It was probably during this renovation that the Proutys moved the kitchen from its original location (our Research Room). You can still see the brick fireplace and bake oven here. By the time Phineas and Adelaide married, they would have had had a wood or coal burning cookstove. It may have vented up the old fireplace chimney. In moving the dining room, it made sense to move the kitchen to the north side of the basement near the dumbwaiter. This may be when they installed a coal chute where the northwest basement window is today. A photo from circa 1876 shows a stable or carriage house at the end of the driveway, where the Hucker Gallery is today, with a porch or veranda above it. This was accessible through the back of the rear parlor. There was also a balcony connecting the three second-floor rooms on the back of the house.

The result of these changes was a fashionable house. The new façade, clearly visible to anyone on the street, was in the popular Italianate style. The entry, hall, waiting room, and dining room, all spaces open to visitors, were created or redesigned to separate visitors from the working and private spaces of the house. Today this space is open and accessible to visitors, whereas the Proutys would have kept all the doors from the hall closed. Visitors could not see anything beyond what they put out for display. The Proutys were proud of their house. The only family photos we have of them are from the 1870s and show them standing in front of it.

The wooden beadboard paneling and beams in the 1883 addition reflect a more casual and private space.

The final change the Proutys made to the house was adding a second floor to the south wing in 1883. They called this space the studio. As Phineas had an interest in art and Adelaide in music, it is unclear whether they used the room for art or music or both. With windows in three walls, it would have had good light. The interior, if it still reflects the original, was not designed for show. The floors are plain hardwoods, and the room has visible beams. White beadboard paneling covers the walls and ceiling like a porch. The wing has a mansard roof and exterior wood details on the windows. Today we use this room to store our clothing collection.

The Proutys in front of their house c. 1876. You can see the stable and carriage house at the bottom of the driveway.

Over their occupation of 50 years, the Proutys made this house their own. Next time, we will see how the Prouty-Chew House changed in the 20th century as it shifted from residence to museum.

Sources

Clifford Edward Clark Jr., The American family home, 1800-1960. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1986.

Phineas Prouty, Sr. and His Family Legacy, Part I

Phin and Kit: The Prouty Family Legacy Part II

The Next Generation: The Prouty Family Legacy Part III