The Next Generation: The Prouty Family Legacy Part III

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

In my previous post about the Prouty family, we got an intimate look at the early married years of Phineas Prouty Jr. and his wife Adelaide. Their personal experiences from 1855 to 1862 are well-documented in their diaries, which are part of our archival collection. While these diaries contain details of their daily life, there are still many holes in the family’s story. For one, someone cut pages out of Adelaide’s earliest diary, including those dating to the birth of her first child. As a historian you itch to know what those pages contained. Another gap lies in the middle years of their life together. Their youngest daughter Anna was born in 1864 and we have a scrapbook that seems to have belonged to her. In it are diary quotes from the later 1860s to the early 1880s, years for which we have no diaries. We do have another set of her diaries from 1886 through 1890, ending before Phineas Jr.’s final illness and death. The life portrayed in the later diaries is very different from what she wrote about as a young wife and mother. Although she still had children in the house, most were adults and often traveled out of town. Much of what she wrote focused on their youngest child and only son, Phineas, born 1875. She mentions her husband only occasionally, and her accounts of her day are more abbreviated and less introspective. In comparison to her earlier struggles with housework, she rarely mentions servants or troubles with them.

We can trace Phineas’ business activities during these years through property records and the newspaper. When his father, Phineas Prouty Sr. died in early 1862, he left a large estate of about $60,000 behind. The Seneca Street building and hardware business went to his son, along with the house at 543 South Main Street and all its contents, equipment, tools, horses and conveyances (vehicles). He left his two daughters and their heirs equal shares of two commercial properties he owned on Exchange Street. His remaining estate (primarily other real estate holdings) was divided into three parts. One went directly to his son, the other two parts were held in trusts for his daughters Harriet Hillhouse and Sarah Augusta Chew under the trusteeship of their brother and husbands. The proceeds from the trusts were to provide an income for the women for their lives and then to be passed on to their heirs. In a time when women were generally considered incapable of managing their money, this arrangement was ordinary.

Phineas Jr. and Alex Chew sold the hardware business to Underhill and Bellows in April 1864, but Phineas retained ownership of the Seneca Street building. Afterwards he likely pursued his interests in art, hunting, and fishing as mentioned in his 1859 diary. He used the wealth acquired from his father to invest in concerns like the First National Bank of Geneva, the Geneva Saving Bank, the Geneva Optical Company, the Geneva and Ithaca Railroad, Geneva Water Works Co., Phillips and Clark Stove Co., and the Geneva Preserving Company. His brothers-in-law were both also involved in several of these businesses. At the same time, Phineas continued his community service as a school trustee through 1879, as a commissioner of Glenwood Cemetery, as a founding member of the Geneva Historical Society, and as a Vice President of the local YMCA at its founding. These financial successes reaped significant rewards, but at a cost.

At the same time that Phineas was successfully expanding his family wealth, he and Adelaide had several more children. Harriet (Hatty) in 1862, Anna (Granty) in 1864, Grace Beverly in 1867, and Phineas III in 1875. A photo scrapbook owned by Granty and Mrs. Prouty’s later diaries indicate that they spent time with the children of other well-to-do families, like their Chew and Hillhouse cousins, the VerPlancks, Sewards, Folgers, and DeLanceys. These children came of age during the post-war industrial boom, a time of rapidly expanding wealth and privilege for the American upper middle class.

Despite their father’s position as a school trustee, none of the Prouty children attended public schools. The girls went to various private girls schools in and around Geneva and in Baltimore and New York City. Phineas III attended private schools and was also instructed by his mother. All of the children had lessons in music and art. They went riding and visiting around town, had picnics at Kashong Point, and stayed at their grandparents’ home, “Rabbit Hill,” located near Glass Factory Bay. Mrs. Prouty spent the winter of 1877 at the Clifton Springs Sanitarium while the four girls attended the Foster School in that village. The family traveled out of town, staying at Narragansett Pier in Rhode Island and visiting the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. During the 1878-79 diphtheria epidemic, they went to Baltimore and did not return to Geneva for nearly a year.

Despite their privilege, the fear of loss expressed in Mrs. Prouty’s diary during the 1850s was very real. All the children fell ill in fall 1868, baby Grace dangerously so. The ten-month-old died November 8. This would not be the family’s only tragedy.

Anna (with the parasol) watches a baseball game on the Hobart campus with Mr. Hayes, Susie Smith, May Sill and Mr. Evans.

According to the documents in our collection and the local newspapers, as they grew up, the girls had an active social life. They participated in social events at Hobart College, performed in theatricals to raise funds for various groups, and were active members of Trinity Episcopal Church. They were part of the east coast upper class social circle and connected with other families on their travels and at their schools. They attended fancy dress parties, went to Hobart baseball games, and played tennis.

All of this social activity achieved its primary aim—the girls all found husbands. Milly was the first to marry. On January 10, 1884, Augustus Swift, a graduate of Hobart, a teacher, and writer became the Proutys first son-in-law. After a wedding at the house on South Main Street, the couple headed to New York and a steamer bound for a European honeymoon. Sisters Hatty and Allie joined them in New York to see them off, staying at the house of family friends.

By the end of month, Hatty was reported to be very ill with gastric fever.1 She died March 12 in New York. Her body was brought back to Geneva for burial in Glenwood. The newspaper announcement of her death described her as the “very life of Main street society” and that it would make for “a dismal Commencement at Hobart” in June. To compound the family’s sorrow, word came that Milly’s husband was also very ill with malarial fever in Italy. He died March 27, and Mrs. Prouty and Allie raced to Europe to join Milly.

Anna Prouty and her friend Jennie VerPlanck in April 1884 while Anna was in deep mourning for Hatty’s death.

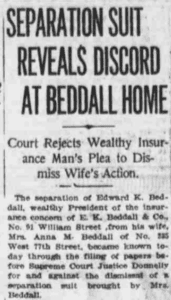

Adelaide Prouty’s diaries from 1886-1890 note her annual remembrance of Hatty’s loss and her continuing fear for her family. In other respects, their lives went on as usual. Milly rented a house on South Main Street, and in 1886 she and her sister Anna toured Europe with friends. Allie married in 1887 and moved to Philadelphia. Milly married again in 1889, to Reverend Richard Harlan, son of the Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan and uncle of the future Supreme Court Justice of the same name. Anna received her father’s blessing for her marriage to Edward Kirkpatrick Beddall just prior to Phineas Jr.’s death in July, 1891. Ill for several years prior to his death, Phineas seems to have retreated from active involvement in the community. Nonetheless, he was one of the richest men in town, and his estate was substantial, totaling more than $500,000.

In his will, he left Adelaide the use of the house and its contents along with income from one-third of his holdings to be held in trust for the remainder of her life, unless she remarried. These or income from their sale would then go to Phineas III. Like his father, Phineas Jr. left the remainder of his estate divided among his four children. Although Millie was 34 years old when her father died, she and her adult sisters all received their funds allocated to trusts administered by their mother and Milly and Allie’s husbands. Only 15 at his father’s death, Phineas III’s estate was also left in trust under the same executors, but with the provision that he would gain control of the funds when he turned 25. His sisters would never have that right.

From the evidence available, the wealth Phineas Prouty Jr. left behind upset more than one family’s harmony. Trouble appears in the record in 1902, after Adelaide died and Phineas III came into his majority. A notice in the Geneva Daily Times indicates that Anna Prouty Beddall and her husband wanted an accounting of the management of the trust, as the heirs had not had one in ten years. Milly was by then 46 years old and had no children. If she died with no heirs, her trust would go to her siblings. Further details emerge in a biography of Justice John Marshall Harlan, Richard Harlan’s nephew. Apparently Milly’s husband had full control of her trust by the early 1900s and he proved to be a poor financial manager. He had made several bad investments that he and his brothers attempted to cover up to avoid scandal. The result was infighting amongst the brothers and 15 years of legal battles between the three of them and the Prouty heirs. This explains the two full boxes of records relating to Phineas Prouty Jr’s estate held at Ontario County Records and Archive, which I’ve not yet dug into.

Milly and her husband ended up in Washington, D.C. and died within days of one another in 1931. Allie lived in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania and had three children. She died in 1943. Over the course of the legal battle, Anna’s marriage fell apart. Her husband went to Nevada to obtain a divorce and the scandal was all over the New York papers. It was later discovered that he had squandered $90,000 of her inheritance. Anna died in 1943 and is buried in Glenwood with her parents. She was survived by two children. Ironically, Phineas III was the youngest, but died first in 1926 at just 51. He married Frances Jerome and they had several children, one named Phineas Prouty. He went to California, where his descendants still seem to live.

Phineas Prouty just a few years before his death. Adelaide (left) and Phineas (right) on their back veranda with their daughter Allie (seated, center), Adelaide’s mother (seated in chair) and several unidentified friends.

Footnotes

[1] In the process of preparing this blog, the miracle of digitization and the Internet brought new information to light. I found the record of a New York City marriage certificate for Hatty Prouty dated two weeks before her death. The groom, George Porter, was a student from Hobart who had performed in a play with her the prior fall. There is no indication in her death notices or the materials in our collection that she was ever married or engaged. This has raised new questions: Was it a deathbed marriage? Was her gastric distress a pregnancy? Her mother signed the certificate, but did her father know she married? Perhaps her death certificate will reveal more. It is not yet scanned for viewing, but when it is perhaps we will know more. It is likely I will never know the answers to all of these questions, but if I find out more, there may be another Prouty family blog in the future!

Sources

Yarbrough, Tinsley E. John Marshall Harlan: Great Dissenter of the Warren Court. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. Digital edition available for loan through the Internet Public Library with an account here. Pages 35-41 detail the legal disputes over Phineas Prouty’s estate.

Many sources and documents regarding the Prouty family and their friends and associates can be found online for free through familysearch.org, which has digitized versions of Ontario County property records and many census, marriage, birth and death records.

Phineas Prouty, Sr. and His Family Legacy, Part I

Phin and Kit: The Prouty Family Legacy Part II