Geneva 1879: Year in Review

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

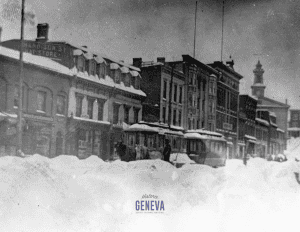

For several years in the late 1800s, the Geneva Courier newspaper published a column in the first or last issue of the year listing events that had happened in the year past. Most columns were dominated by death notices, but in 1879 they must have been short of other content because they included several columns listing dozens of events for each month of 1879. The year started out with a snowstorm on January 8 that paralyzed Geneva and the surrounding area for three days. The community was cut off from the outside world, except for telegraph communication. Few wagons and no trains came or went, so there was no mail or news of even the nearby villages during the storm. The steamboats didn’t leave their docks due to the wind and trains were stuck on the lines especially between Geneva and Ithaca. One of the heaviest drifts was on the tracks near Rose Hill. Farmers entertained snow bound rail passengers near their homes. Although trains could be sent out with ploughs attached to clear the tracks, most of the tracks were cleared by gangs of men shoveling them out.

In March and April, the Courier reported stories of workplace injuries that were all too common in the 1800s. On March 19, Farmer Aaron C. Rippey of Stanley lost a hand to a horse-powered corn husker. One of the stalks he was feeding into it looped around his hand and pulled it in. Doctors had to amputate the hand. Were it not for the quick actions of his relatives, he might have been pulled fully into the husker. The man had already lost two or three fingers in the prior year, demonstrating the hazardous nature of life and farm work in 1879. Things went worse for 69-year-old farmer Richard Andrews, who was killed in Bellona. He was holding a stake another man was driving into the ground with a sledgehammer when the head flew off the hammer and struck him in the pit of his stomach. The Courier indicated a similar incident had broken another farmer’s arm in the previous year.

In June the paper reported that there would be a concert at Linden Hall for the benefit of the Kansas refugees. It took me some searching to figure out who these refugees were since it was the only mention of this term I could find in the Geneva newspapers. The people are more commonly known as the Exodusters, or the formerly enslaved who migrated to Kansas from the Southern states after the Civil War. Reconstruction ended with the withdrawal of federal troops in 1877. African Americans quickly found themselves trapped in a new form of servitude as the Jim Crow laws were established. Many who hoped for better opportunities moved west. Kansas was both close and associated with abolition because of the reputation of John Brown and the pre-war violence over the expansion of slavery into the state. The African American population in Kansas swelled from 17,108 in 1870 to 43,107 in 1880. Many of these migrants crossed the Mississippi to St. Louis, Missouri in 1879. They arrived destitute and with no means of supporting themselves or their families or continuing their journey. Communities across the north began to collect funds to help them and the Geneva concert was part of these fundraising efforts.

In September 1879, area towns celebrated the centennial of the Sullivan-Clinton campaign during the War for Independence. This was the march by Major General John Sullivan to stop Seneca and Loyalist incursions against eastern settlements by burning Haudenosaunee villages and food stores to the ground and destroying their political power. After reporting on celebrations in Seneca County, the editor of the Courier took the opportunity to point out that the celebrations were held in Waterloo, not Geneva. That Waterloo had a monument to the march, not Geneva. That Waterloo had a Historical Society, not Geneva. “In all soberness we ought to be ashamed. Thirty years ago, the pride of Geneva in her past ought to have roused her to make secure for posterity the wasting memorials of her border days, and the recollection of her aged citizens.” He went on to mention George Conover’s work to record Geneva’s history, including collecting Native American relics. He advocated for “two or three gentlemen of weight and standing” to organize a Historical Society. He hoped that they could preserve the remains of Kanadasaga and that September 7 and 8 would become an annual local holiday. While he was wrong about the holiday, four years later a sufficiently distinguished group of 14 men gathered to form the Geneva Historical Society on May 22, 1883. Early meetings featured conversations among the members, discussing what the village once looked like and reminiscing about the citizens that had lived in it.

The village was steadily growing in these years and had just over 5,800 residents. Several notices show the growing pains resulting from increased population and mobility after the Civil War. In December, there were two reports of assaults and robberies on women near Genesee Street. Both crimes were supposed to be committed by the same man. The piece concluded that “some measures should be taken to put a stop to these rascalities and punish the perpetrators.” Complaints, the editor wrote, were made almost nightly of disturbances by drunken men. Elsewhere he reported that a new system of “keeping tramps” (rather than arresting them) had kept 200 tramps in 2 months at just $100. The prior practice, he estimated, would have cost $500. In the same issue, the formation of a Village Relief Committee, presumably to deal with problems of poverty and homelessness, was reported. Following that piece was a notice urging the creation of a public and social organization to meet the needs of young men.

While not a comprehensive survey of the year, the 1879 review of Geneva’s activities gives a portrait of a small town moving forward in a changing world.

This article was brought to you in part by our supporters. Be our partner in telling Geneva’s stories by becoming a Historic Geneva supporter.

Anne,

Enjoyed reading your article. Thank goodness we don’t now have snow like shown in the photo.

Thanks Charlie, but watch out what you say! You never know!

It seems hypocritical to celebrate the destruction of the Haudenosaunee villages by making a holiday of the Sullivan-Clinton campaign and at the same time make efforts to preserve the remains of Kanadasaga.

I think the idea was that this is the area’s one connection to the Revolution and the early history of the Republic and it should be celebrated. This was just a few years after the Centennial, and Americans had only recently begun to think about their history. It was also the period of the Indian wars in the west. I suspect treating Native sites and people as a relic of the past made removing the actual people from their lands in the present easier.