Sampson’s Laborers and Geneva’s Housing Crisis

By Andrew Pilet, Hobart College Intern

Spurred on by growing US involvement against the Japanese in the Pacific, the construction of a naval base on the eastern side of Seneca Lake was approved by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on May 14, 1942.1

The area was chosen for having relatively flat, well-maintained land next to a body of water capable of handling a small-craft fleet; being inland, safe from attacks on the coast; and being accessible by railroads and highways, with adequate disposal facilities and water sources. Of special note, among these needs, was for “proximity to a city able to serve as liberty port.”2 While Sampson US Naval Training Station, relied on support from numerous towns in the area (Waterloo, Penn Yan, Ovid, Seneca Falls, etc.), Geneva served the role of a ‘liberty port’.

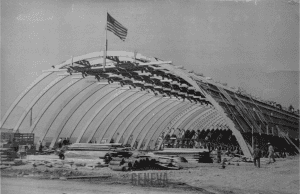

The contractors (John H. Johnson and Mount Vernon Contracting Corps.) estimated that the station, comprising more than four hundred buildings, would require somewhere between twelve to fifteen thousand laborers. Most skilled laborers had to be brought in from elsewhere, predominantly New York City.3 For this purpose, the contractors opened employment offices on Castle Street in Geneva, bringing in more than six thousand skilled laborers by May 29, 1942.4

Construction on June 1, 1942, barely two weeks after being approved.5 With 46,000 workers, it took 270 days and $52,000,000 to build the station.6

Prior to Sampson, the Great Depression (1929-1939) had stalled housing construction, and only 1.6 percent of vacant property was for sale.7 Leonard Kornet, a civilian administrator at the nearby Seneca Ordnance Depot, remembers that housing was scarce in Geneva even in 1941, the year prior to Sampson’s construction.8 Sampson arrival did not create a housing problem, but fueled a pre-existing crisis.

With thousands of laborers imminently approaching Sampson and Seneca Lake, the contractors and government worked quickly to procure housing. A Housing Bureau was opened in Geneva in the latter end of May 1942. The Geneva City Chamber of Commerce found that eight to eleven thousand room listings could be found across Geneva and nearby towns. Public health authorities found, however, that only six thousand rooms were able to be filled without overtaxing sanitary facilities. Forms were sent to all settlements in a forty mile radius seeking vacant family dwelling units for rent, while emergency residences like trailer camps were established on private properties and along the lakeshore. The “patriotic instincts of home owners” were appealed to, so as “to make available ‘that spare room’ regardless of their financial status.”9

The city’s housing coordinator, R.C. Shreve reported in August 1942 that “many persons [had] gone to the expenses of repapering, refurnishing rooms, and making other changes in anticipation of roomers which [had] so far not appeared.” Shreve, alongside state labor official C.H. Freeman seemed to find that housing in Geneva was abundant. They saw no evidence of a shortage, and reported that six thousand of apparently eighteen thousand rooms were still vacant in Geneva by the end of August.10 Likewise, the contractors argued that the trouble with housing the laborers was not due to a shortage, but instead the scarcity of buses and trains to Sampson.11

The historical record would suggest, then, that Geneva, as a ‘settlement’, was adequately prepared for the ensuing masses of workers entering the city. However, the actual course of the housing crisis that followed reveals how unprepared (and resistant) Geneva really was.

In early August 1942, while Shreve and Freeman were making their reports, eighty laborers had occupied city jail cells on their first night, and others had slept in a park.12 Temporary housing was set up in places like the courthouse, Dove building, and the Danc’ Inn, while residents were continually pushed by city and government authorities to convert and list their garages and rooms as units.13 Merchants like Charles Wheeler, a furniture store owner, capitalized on the growing need to ‘furnish’ these rooms for sudden renters.14

Meanwhile, many workers lived in “tents, sheds, cars, [and] barns.” Because the city and its citizens believed the majority of these workers would leave once construction was done, most of the housing specifically built for them was temporary and substandard.15

The onus to house these workers ultimately fell upon the citizens of Geneva, their patriotism being tied to their willingness to cede their rooms and homes to “outsiders.” As such, some of their animosity towards the mass of laborers can be explained as pure fatigue. Yet Navy officers, who were searching for homes as well, were viewed with more respect and appreciation.16

One Rochester newspaper explained that Geneva had become a “boom town,” its streets crowded, hotels and rooms filled with people “whose manners [were] strange to Geneva” and vice versa.17 An article in Time Magazine gave a glum image of wartime Geneva, writing:

Geneva, instead of having a 10% earnest young Americans learning to be soldiers, had a 100% influx of roughneck workmen — 15,000 men, any sort of tough riffraff whom contractors could hire at high pay to build a big naval training station on Seneca Lake. All Geneva’s spare rooms were let; cots filled the City Hall, an old movie house, a dance hall, hotel corridors. The once quiet, orderly town nearly went mad. Buses were so jammed that sometimes drivers had to threaten unruly crowds with wrenches in order to make them let passengers out. Decent bars became clamorous dives. Honest citizens dared not let their daughters go out after dark. More policemen were hired but holdups and disorders mounted. Staid, tradition-loving Geneva felt its life was ruined. Everybody was miserable.18

Leonard Kornet remembered there was always a general tension between the Depot/Sampson workers and Genevans, who believed they were unreliable and would not pay.19 Geneva and the Geneva Daily Times associated the influx of laborers with a “budding local crime wave” of 226 cases in August compared to just 83 in June — largely the result of public intoxication and prostitution.20

At the same time, these workers were a source of great prosperity for the city and its citizens. With a payroll total of more than one million dollars a week, the laborers provided essential income to local businesses and homeowners. Renting a room, beyond feeling like a national obligation, became a financial incentive.21 Caroline Hobbins, who operated The Seneca Shop with her husband around this time, remembers Sampson’s presence as making a “big difference” to them. She viewed the bases’ sailors as the primary providers, though, while its laborers “weren’t of any great help […] except they crowded the eating places and everything like that.”22

This view of the laborers was not uncommon. In Close to the Heart of War: Geneva and World War II, Kathryn Grover argues that Geneva seems to have “acknowledged the sailors and their families more openly than it did the construction workers who preceded them.” Two residents, McNerney and Buckley, remembered the “whole town turn[ing] out to take care of the situation,” that being the housing of the sailors.23 Rather than addressing the way Geneva similarly opened up for the laborers building the base, they discuss, glowingly, how the sailors were accepted into the community — as though the former was a burden alone.24

The workers were viewed with suspicion, to the point that the naval base’s high turnover rate was equally attributed to opportunistic travelers seeking to make home in the Finger Lakes (and being fired for incompetency) as it was to the lack of housing and transportation.25

As Grover establishes, “many Sampson laborers were poor men.”26 Due to a shortage of white construction workers, around 7,000 of the 25,000 workers that ended up working on the base (and the Seneca Depot) were Black, many of whom were overwhelmingly rejected places to live due to a lack of segregated housing.27

Unlike the sailors coming through Sampson, these laborers who built it were treated to inadequate living conditions. Many of them had trouble with dysentery and typhoid.28 As the war continued, more housing was built to hold the construction workers and military personnel. The Dixon Victory Homes, a 250-unit residence completed in 1943 and not meant to last more than a decade, ultimately failed to fill up more than fifty apartments by 1944.29

Homes like these, and other rental properties throughout Geneva, were decried for being “not only limited but substandard,” due to a lack of private baths and toilets, dilapidated structures, and higher rent than comparable residences in Waterloo and Seneca Falls.30 The primary occupants of these homes were Black. Beyond the stress of listing and housing workers, an occasional complaint of homeowning Genevans during this same time was an imposed rent freeze on the city.31 The laborers, sailors, and local residents were living in different worlds, spurred on by the industry and momentum of the Sampson Naval Base.

Dixon Homes were housing units constructed in Geneva by the Federal Housing Authority to accommodate the influx of population.

The latter end of the war saw new, otherwise unchallenged shifts in housing in Geneva. Constant construction at Sampson kept a regular flow of workers who still needed homes.32 Alongside the Dixon Victory Homes, additional units were made by converting single family homes, institution buildings, and the upper floors of downtown businesses into apartments. Ehrlich and White won contracts for the federal government’s housing conversion program, turning five homes on South Main Street, three on Castle Street, three on Genesee Street, and two each on Pulteney and William Streets into apartments.33 By war’s end, workers were being displaced by veterans and the families of servicemen.34

The construction of the Sampson Naval Base corresponded with a housing crisis in Geneva. The burden which fell upon the resident population of the city fell just as hard on the lives and legacies of those who built the base — the thousands of laborers who entered the city, undiscussed and distrusted.

Bibliography

Caroline Hobbins Interview with Dr. George Hucker. Aug 13, 1975.

Chapin, Becky. “From Pre-Emption Park to Courtyard Apartments.” Historic Geneva, Feb 9, 2024.

“Construction Of New Unit Has Been Approved For Sampson.” Sept 10, 1943.

Grover, Kathryn. Make a Way Somehow: African American Life in a Northern Community, 1790-1965. Syracuse University Press, 1994.

Grover, Kathryn. Close to the Heart of the War: Geneva and World War II. Geneva Historical Society, 1995.

Leonard Kornet Interview with Dr. George Hucker. Aug 12, 1976.

Merrill, Arch. Slim Fingers Beckon. Creek Books, 1951.

“Program of Distribution Of War Housing Will Not Affect Geneva At Present.” Geneva Daily Times, Oct 2, 1945.

“Sampson Naval Training Station, Romulus, New York, 1942 – 1946.” The Naval Archives.

Shaplen, Robert. “Sampson a Triumph of Fast Engineering.” Geneva Daily Times, May 22, 1943.

Watrous, Hilda R. The County Between the Lakes: A History of Seneca County, New York 1879-1982. Seneca County Board of Supervisors, 1982.

“Work Started On Naval Station.” May 29, 1942.

Footnotes

1 “Sampson Naval Training Station, Romulus, New York, 1942 – 1946;.” Watrous, p. 39.

2 Watrous, p. 39.

3 Grover, Make a Way Somehow, p. 46; “Work Started.”

4 “Work Started.”

5 Ibid.

6 “Sampson.”

7 Grover, Close to the Heart of the War, p. 32.

8 Leonard Kornet Interview..

9 “Sampson.”

10 Grover, Close to the Heart of War, 21.

11 Ibid, 33.

12 Watrous, 44.

13 Shaplen.

14 Watrous, 44; Grover, Close to the Heat of War, 26.

15 Grover, Make A Way Somehow, 91.

16 Grover, Close to the Heart of War, 26, 23.

17 Ibid, 22.

18 Ibid, 23.

19 Leonard Kornet Interview.

20 Ibid, 21, 37.

21 Watrous, 45.

22 Caroline Hobbins Interview

23 Grover, Close to the Heart of War, 31.

24 Ibid, 23.

25 Ibid., 20.

26 Ibid, 21.

27 Ibid., 21; Grover, Somehow, 47.

28 Grover, Close to the Heart of War, 25.

29 Chapin.

30 Grover, Make A Way Somehow, 91.

31 Grover, Close to the Heart of War, 33.

32 “Construction Of New Unit.”

33 Grover, Close to the Heart of the War, 34-35.

34 “Program of Distribution,” 3

This article was brought to you in part by our supporters. Be our partner in telling Geneva’s stories by becoming a Historic Geneva supporter.