Sustainable Agriculture, c. 1860

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

As they say, everything old is new again. Sustainable agriculture helped 19th-century farmer Robert Swan and his father-in-law create successful farms.

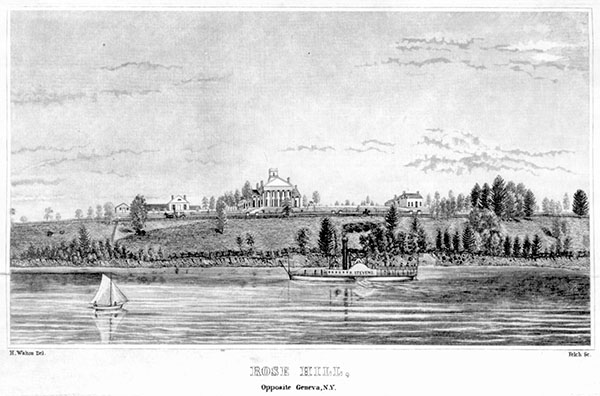

In May of 1850, Robert and Margaret Swan took up residence at their new property on Seneca Lake. According to several sources, the farm was not in great shape, but had, as we might say today, potential. Certainly Robert knew this from his time living on the Johnston Farm just next door. Rose Hill Farm was comprised of 350 acres and was purchased by Robert’s parents as a wedding gift for the young couple. The previous owners, the Van Giesons and their relative, William Strong (builder of the mansion), had not been farmers and probably leased the land out to tenants who farmed it. As a consequence:

It was then in the ordinary condition of farms in that section of country, and being a wet, tenacious soil, the crops were, except in very favorable seasons, small. The farm was very indifferently fenced—filled with swales and sunken places, where coarse aquatic grasses and noxious weeds had full possession. Here was a work of no ordinary importance for a young man, just entering upon his career, as a farmer. [New York Agricultural Society Transactions, 1857].

Likely too busy to keep much account of his doings the first year after his marriage, we have no records of his farming during 1850. He probably spent much of that time repairing fences and deciding what he would plant and where. We have both an account book he kept from 1851 to 1862 and a journal of his activities on the farm for 1851 to 1858. These, combined with family letters and articles about farming in the state farm journals, give us a fair idea of how he worked his farm.

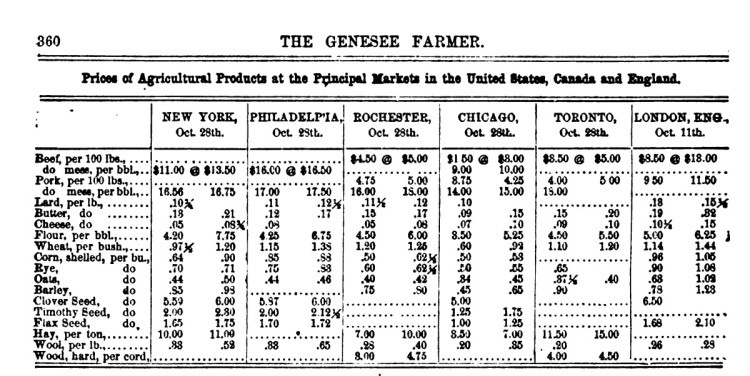

Robert, like his mentor and father-in-law John Johnston, grew wheat as his chief crop. He also grew oats, corn and grass for forage (timothy grass and clover) every year. Some years he mentions barley and buckwheat, but it is unclear if he grew these annually. He had sheep, cattle and pigs on the farm, as well as horses for transportation.

In upstate New York, farmers plant wheat in the fall and harvest in early July. Robert must have planted in fall of 1850 because he started harvesting 58 acres of wheat on July 19 and wrote it looked to be a “fare [sic] crop.” The next year did not go so well, beginning with dry weather in September when he planted the wheat and a cold spring. These conditions were followed by grasshoppers at harvest time. By July he wrote,

“My wheat looks miserable enough. I don’t think I will Average 10 Bushels an Acre. I Shall only sow 25 or 30 Acres of wheat this Fall. Drain more, manure more, & have more of my farm in grass, & by this means I will by & by make more grass, & by this means I will by & by make more out of it than having so much in crop.”

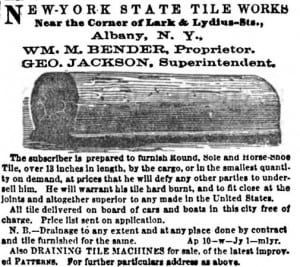

And drain he did. Over the next two years he laid over 60 miles of drain tile on 305 of his acreage. He reported that this cost him $0.30 per rod (16.5 feet) or $96.00 per mile. This brought the total cost of drainage to $5,823. He wrote in his application for the State Farm Premium,

“This land reclaimed, is now equal to any land upon the farm, and in the field of 60 acres of wheat raised the present year [1857], about fifteen acres of it was land reclaimed; and the wheat upon that portion was equal to the very best of the field.” [NYAS Transactions, 1857].

His wheat yields grew from five bushels an acre in 1852 to 20 bushels per acre in 1857, a year when the wheat midge damaged portions of the crop. By 1862, Rose Hill averaged 40 bushels an acre, just short of the modern American average of 46 bushels for a non-irrigated farm.

He followed Johnston’s method of farming: raise sheep and cattle for manure, meat, milk and wool; raise grass, corn, and clover for feed and bedding straw; spread rotted straw and manure on the fields to feed the crops; sell livestock and butter for cash; use cash and credit to drain the land. Johnston and Swan also made sure to rotate crops, leaving wheat fields fallow for portions of the year or growing clover on them to restore the soil’s fertility. In many ways, this is what we would today call a sustainable agriculture system. Swan grew crops to feed livestock, and the livestock fed the land to grow better crops. According to one article about the farm, every crop grown on it was consumed except wheat, which was the most profitable crop to sell.

This method relied on a formula of “Dung, Drainage and Credit.” The farmer needed to drain and manure. To do both he needed credit until his farm proved profitable. While John Johnston had to invest his profits in draining his land a little at a time, Robert Swan’s access to credit (likely due to his father’s connections) meant he could drain his entire farm more quickly and profit more quickly. Even the modern farmer would probably say that with credit, nearly anything in farming is possible.

Do you have the Henry Walton print of Rose Hill in your collection?