Keeping Up With The Times

By John Marks, Curator of Collections and Exhibits

There’s a great line in the first Men In Black movie. Tommy Lee Jones is showing Will Smith alien technology, including a tiny compact disc, and says, “Looks like I’ll have to buy the White Album again.” Whether or not you liked the Beatles, it resonated with anyone who saw the change from vinyl records to tape (8-tracks and cassettes) to compact disc. In the 1990s I bought CDs of my favorite vinyl; now I’m buying vinyl from the 1980s of albums that I once had on cassette.

In modern terms, this is called reformatting. It’s not new and we deal with it every day in the museum. Photographs are the most common example. The earliest images were direct to a plate; they didn’t have a negative that could be duplicated. As negative photography developed, families had a new photo made of old daguerreotypes and tintypes.

Negatives went through many changes. (There are a number of good

books on the history of photography if you’re interested.) There were several processes – wet plate v. dry plate – but the image was made on glass plates.

books on the history of photography if you’re interested.) There were several processes – wet plate v. dry plate – but the image was made on glass plates.

In 1883 George Eastman revolutionized photography with his invention of dry process flexible (or rolled) film. The size of film varied widely, depending upon the camera and the user. Graflex cameras, used by photojournalists through the 20th century, used single sheet film from 2” x 3” to 5” x 7”. Other camera styles used even larger film.

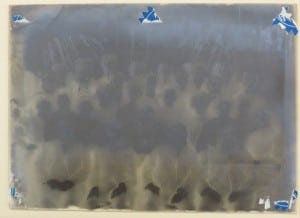

The early flexible film was nitrate based, which is highly flammable and can auto-ignite. Many such negatives have been copied onto safety film. (If you find old negatives that have become gooey, smell bad, or are not marked “safety film”, call a professional. DO NOT destroy by burning yourself as nitrate fires are difficult to extinguish.)

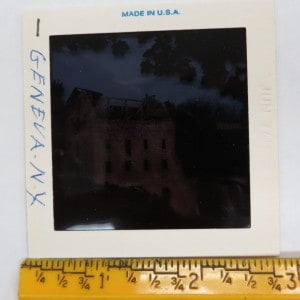

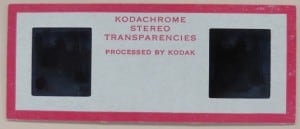

The situation was repeated when color transparency, or slide, film came along. There was a standard size, but some were larger or smaller (remember the 110 pocket cameras of the 1970s?). There were even stereo slides.

All these examples are from the GHS collection. Reformatting challenges are these:

Traditional reproduction. While we had a darkroom into the 1990s, it’s impractical to do our own photo developing. We can send odd-sized negatives out for printing but it’s becoming harder to find companies.

Traditional reproduction. While we had a darkroom into the 1990s, it’s impractical to do our own photo developing. We can send odd-sized negatives out for printing but it’s becoming harder to find companies.

Scanning. Visitors are shocked (and sometimes outraged) that we haven’t digitized everything in our collection. Scanning of transparencies requires a special scanner and a lot of staff time. Outsourced scanning still requires staff prep time, and money.

Viewing. There is no easy way to quickly view negatives and slides. We have two large light boxes, but it’s still slow going with thousands of images. We have slide projectors and carousels but they require loading and unloading.

There’s a quick-and-dirty method of digitizing transparencies. I put them on a light box and take a digital photo from a tripod. Negatives can be inverted to positive images with photo software. The quality isn’t perfect but it gives us a digital record of what we have.

There’s a quick-and-dirty method of digitizing transparencies. I put them on a light box and take a digital photo from a tripod. Negatives can be inverted to positive images with photo software. The quality isn’t perfect but it gives us a digital record of what we have.

711 South Main Street, Phi Phi Delta fraternity house. This was the right-hand image on the stereo slide.

Our mission is to preserve and present Geneva’s history. We can preserve images in their original format, but we need to reformat them to make them more accessible. If you have a special interest in this and want to volunteer time or money, please call us at 789-5151.