Geneva School Expansion and Reform

By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

During the 1800s, Americans were creating new institutions for their new nation. By midcentury, Geneva had a well-supported system of public schools made up of primary and secondary schools. There were four branch schools for children up to 12 years of age. The Classical and Union school provided teacher training and college preparatory classes for older students. This system served the community through the 1870s, but at the end of the century, the Geneva School District experienced a period of expansion and reform that reflected national trends.

Across the nation, Americans were moving from rural to urban areas for new jobs and opportunities. Immigrants with strange languages, religions, and traditions flooded the nation’s ports. People found themselves living in urban areas surrounded by strangers. Many Americans worried that these strangers would not live by American democratic values. They also worried that transplants to cities working in factories would lose their small town values. They believed schools were a way to teach immigrants, the poor, Native Americans, and free blacks how to be good Americans.

Education reformers advocated for standardized school systems to reinforce traditional American beliefs and culture. They wanted to supplant cultures and attitudes that they did not consider American. They promoted sorting children into classes by age, seating them at individual desks in uniform classrooms, and evaluating them with grades and exams. Teachers led children through schoolbook lessons that supported white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant social and racial hierarchies. Schools were to teach children order, self-discipline, self-control, and conformity to rules and regulations. Some cultural groups rebelled against this enculturation, namely Irish Catholics. They created their own system of schools in response.

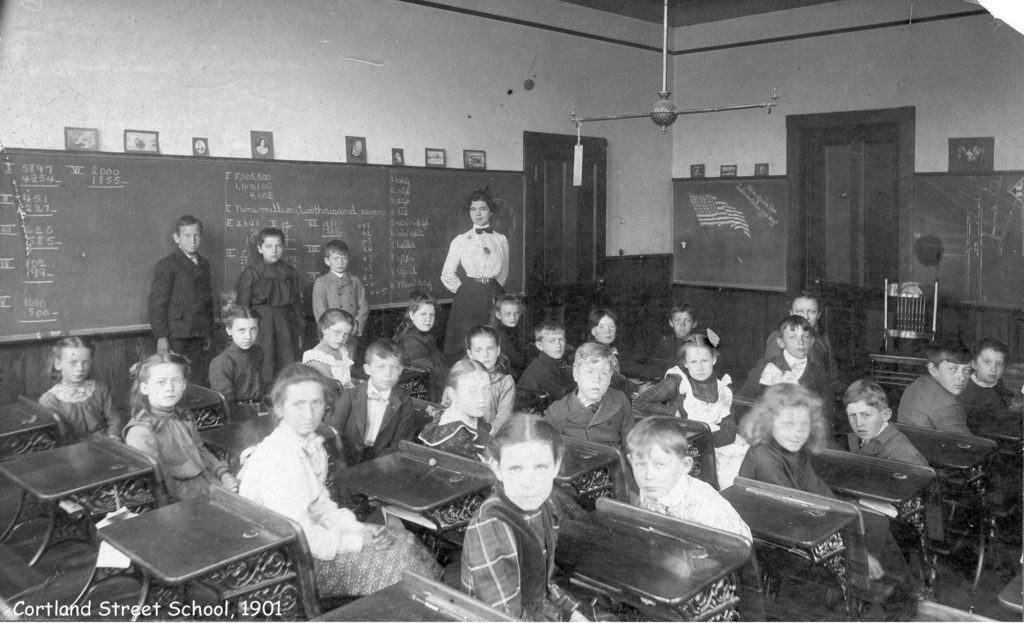

Education reformers put students of the same age in orderly rows. A modern classroom had blackboards, pictures of significant Americans, radiators, and gas lighting.

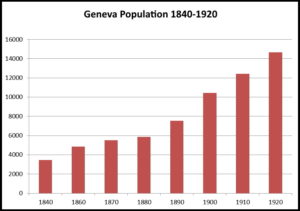

Geneva was also impacted by these late 19th-century changes. The number of people living in Geneva doubled between 1880 and 1910. By 1900, just over 19% of Geneva’s population had been born in a foreign country. In addition to the continuing waves of Irish immigration, the turn of the twentieth century brought new residents to town, including Italians and Syrians. About 8% of the population did not speak English as a native language. These shifts had an impact on all sorts of community institutions, especially the school system.

Education reforms established in large cities trickled into smaller communities like Geneva as well. They spread through publications, the state Normal Schools (teacher training schools), and teacher institutes held around the state. Geneva teachers participated in professional education meetings annually beginning in 1847. At these programs, they heard lectures on academic subjects, methods of organizing the classroom, and new approaches to discipline. Member teachers shared innovative teaching methods like object teaching, and the use of globes, maps, and blackboards.

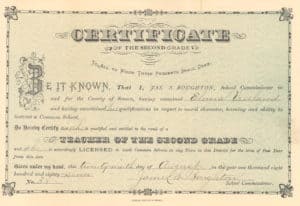

Teachers were examined by local school commissioners who certified whether they were of good moral character and qualified to teach.

In 1879, the school district reformed its curriculum in line with changing ideas about American schools. This included better instruction of younger students in the branch schools. Since the 1839 creation of the Union School, much of the Geneva school trustees’ focus had been on its development. It had an excellent reputation, even drawing paying students from outlying towns and villages. However, it served only a small percentage of Geneva’s children. Although the district constructed branch schools for primary students in 1852, the Classical and Union School received more attention and resources. The newspaper repeatedly editorialized on the neglect of these schools and the importance of primary education. At the January 1879 school board meeting,

It was decided that the prominence which classical instruction has had hitherto in our system give place at least in a measure to a course of instruction adapted to all the children in the schools, and particularly to those who are young or who are to get all their education in the union school.…It was determined to raise the standard in the branch schools, and to provide the children who attend them with more and better supervision.…It will be the endeavor to render these schools as popular in their localities as the central school is….

Later that year, the school board appointed a new administrator and simplified the district’s course of instruction to give “greater prominence to practical studies, the allowance of more time to general lessons…, and [greater]… personal attention and instruction…by the Principal to the primary schools.”

Recognizing that many students would not attend beyond the seventh grade, the board added art, music, and natural science to the primary school curriculum. They created ungraded classes for those students who only attended during the winter months and were behind their peers. They divided the high school course into three tracks: a general course, a commercial English course, and a college preparatory or classical course. In this way, the school district tried to expand the educational offerings for more villagers.

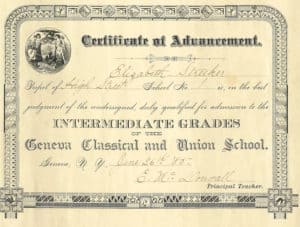

School reforms required students to pass exams and receive certificates to mark their achievements in school.

Increases in the population and advances in school management made the inadequacy of the school buildings evident. Complaints about the overcrowded and poor conditions of the primary schools on High, Lewis, Jackson and Cortland streets began to appear regularly in the newspaper during the last quarter of the 19th century. Built as one-room school houses at midcentury, the buildings did not age well. Their only light came through the windows; pot-bellied stoves provided heat; students used a privy; and the only water came from an outside pump or stream. By the 1870s, many village buildings had central heating systems, gas lights, plumbing, and sewers. Villagers wanted these conveniences in their schools too.

In 1882, Lewis Street School was deemed unsafe and students had to meet in temporary quarters. That November the district reconstructed the school. This building in turn had to accommodate students from Jackson Street when it was closed for repairs that year and later sold. The board authorized the addition of steam heating, water, ventilation, and sewers to schools in the 1880s, but by the early 1890s, the newspapers again reported that all schools needed repairs and expansion. A major renovation was done at the High Street School in 1891. The Union and Classical School, now Geneva High School, required a $14,000 addition in 1892. That same year, the district built a new school on Prospect Avenue to serve the northeast side of town. This was the first primary school to have two floors and capacity for over 150 students. Just a year after this expansion, the Cortland Street School was so overcrowded that children had to attend half days with some going in the morning and others coming in the afternoon. The Geneva Advertiser wrote “It is our misfortune that in building that schoolhouse the district did not prepare for the future. Every branch school hereafter erected here should be two stories high, with room enough for at least 300 to 400 pupils.”

The district was unable to foresee the growth of the town and the increasing proportion of students attending school. Nor were the trustees prepared for New York State’s Compulsory Education Law, effective in 1895. This law required all children 8 to 12 years old to attend school 130 days per year. Again the district had to expand its facilities. From 1895 to 1896 they demolished the Cortland Street School and the 1882 Lewis Street building in favor of new, larger buildings in the style of the Prospect Avenue School.

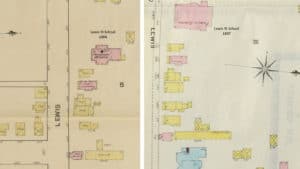

The footprint of Lewis Street School expanded considerably between the 1882 building and the 1896 construction. A second lot was purchased to accommodate the larger school.

Over the course of 25 years, the district had expended over $63,000 on new and improved facilities. By 1900, the main school buildings were in place until the next round of national school reform and expansion in the 1920s. In that decade, new standards led to the construction of both a modern high school and large elementary school. The old Classical and Union School became a Junior High School.

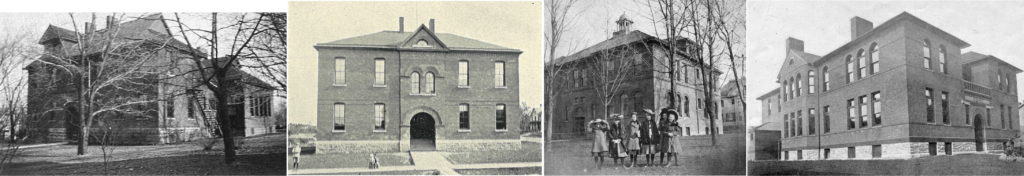

In the 1890s the Geneva School District built or expanded the four branch schools: High Street School, Prospect Avenue School, Cortland Street School and Lewis Street School.

A Note on Sources

Most of the information about the changes made in the school district come from 19th-century newspaper accounts of the annual school meeting. School districts were run by a committee of trustees. The trustees released an annual financial report, which was normally published in the newspaper in December. This information was accompanied by a notice of the annual school meeting, held on the final Saturday in December. Interested tax-paying residents of the school district voted on the funding for the next year at this meeting. Occasionally there were subsequent meetings to approve bond issues, if the trustees wanted to finance a building project. State regulations and reports can also be accessed online. Additional information can be found in secondary histories of education. Many of these are documented extensively in the Bibliography of Barbara Finkelstein’s Governing the Young.

Select References

Finkelstein, Barbara. Governing the Young: Teacher Behavior in Popular Primary Schools in 19th-Century United States, 1989.

Folts, James D. History of the University of the State of New York and the State Education Department, 1784 – 1996.

Fraser, James. Report on the Common School System of the United States and of the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, 1866.

Horner, Harlan Hoyt. Education in New York State, 1784-1954.

Founding of the Geneva School District

Anne, wish I’d known all this when I was on the school board, 1981-91. Very interesting early history.