The Wyoming Valley Massacre

Daniel Mastromarino is a member of the class of 2021 at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. He has worked as an intern here at the Geneva Historical Society this summer through the Colleges’ FLX Summer Internship Program. Part of his work was researching and presenting a short talk on the history of the Sullivan-Clinton Campaign of 1779 at our Rose Hill Through the Ages program on July 21. This military campaign marched right past the site of Rose Hill during General Sullivan’s successful quest to destroy the Iroquois Confederacy’s military and political power during the war for American Independence. If you missed Daniel’s program, here is the first of two blog posts based on his research.

By Daniel Mastromarino

In July 1778, a frontier settlement in Wyoming Valley, Pennsylvania was attacked by a band of Iroquois warriors with the help of Loyalist allies. The same group attacked another settlement in Cherry Valley, New York in November of the same year. Many people were killed during these infamous raids. As a result, the surrounding frontier erupted in a state of panic. George Clinton, the patriot governor of New York, immediately began calling for an expedition to remove the Native American threat in the Finger Lakes region. Even George Washington, the commander of the Continental army, expressed interest in the idea. In March of 1779, the New York Legislature ordered the erection of forts on the western frontier and the recruitment of one thousand men to staff them. Congress authorized funds for a campaign to remove the Loyalist-Indian threat shortly after that. Washington appointed Major General John Sullivan to command the expedition into the Loyalist-Indian territory to eliminate the risk.

The alliance between the Iroquois Confederacy and the British during the American War for Independence was a threat to the Americans. Thus, it was in the best interest of the Americans to make sure the frontier was as secure as possible. At the start of the British and Iroquois alliance, the Native Americans immediately conducted ambushes across the frontier that disrupted American military network and supply routes. It was the attack on the settlements in Cherry Valley and Wyoming Valley that captured the attention of the American army, primarily due to various reports that exaggerated the number of unarmed civilians killed.

At the Battle of Wyoming, many of the American militiamen died by torture, but only 5 Seneca died. Furthermore, after the fort at Wyoming surrendered, the nearby settlements were burned and looted. Most women and children from the settlement fled into the mountains, and the prisoners taken were neither massacred nor tortured. Fifteen prisoners from Wyoming were even sent back to the British at Niagara, where they were given money and clothes before returning home. The survivors of the attack, who fled into the mountains, spread exaggerated stories of atrocities committed by the Indians. However, there were numerous instances before the Battle of Wyoming where the Indians ruthlessly destroyed entire settlements.

Perhaps one of the biggest rumors regarding the attack on Wyoming Valley was the presence of Joseph Brant, who was a Mohawk warrior and the leader of the Iroquois Alliance. Throughout the frontier, he became known as “Monster Brant” for his supposed deeds at Wyoming, yet Brant was not even present during the attack.

Ultimately, it was the successful attacks on Wyoming Valley and Cherry Valley that prompted the Americans to organize a campaign to eliminate the threat. The campaign not only succeeded in its primary mission, but it also eradicated every single Indian settlement and all the livestock they could find in the entire Finger Lakes region. The significance of settlement attacks like Wyoming Valley was that it led to a campaign that ensured the safe future settlement of the Central and Western New York frontier in the years to come.

I’m so sorry that I missed your talk and I thank you for putting this information on your blog.

The vicious murder in 1779 of Iroquois women and children at modern-day Geneva was perhaps the first example of American scorched-earth tactics according to this Geneva local:

https://www.brianwillson.com/the-secret-of-the-arrowheads-summary/

There’s a reason the Indians were siding with the British.

While the Sullivan-Clinton campaign is a little-known scorched-earth campaign of General Washington’s with plenty of atrocities, there is no evidence that anyone was killed in or around Geneva. According to the diary of Sergeant Moses Fellows, the army arrived to find the village of Kanadesaga (Geneva) abandoned, except for a 3-year-old white child they supposed to have been a captive. They proceeded to destroy Butler’s fortifications and the fields of corn, hay and stores in the vicinity. You can find an online version of his account on this blog. Other officers’ accounts can be seen here. Soldiers also recognized the value of the lands they were marching across and some of them returned to settle in the area after the war as a consequence. More deaths likely came about from starvation at Fort Niagara during the extreme winter of 1779-80, where many Iroquois had taken refuge with the British.

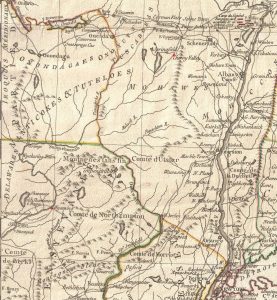

The map is very interesting because it lists river names which are different from what they now are. Specifically it shows a “TienaderHaHa” River which I believe is the Chenango River.

A very poor attempt at revisionist history. Reference the following:

Area History: Battle and Massacre af Wyoming:

Luzerne (then Northumberland) Co, PA

HISTORICAL ADDRESS

at the

WYOMING MONUMENT

3d of July 1878

on the 100th Anniversary of the

BATTLE AND MASSACRE OF WYOMING

by Steuben Jenkins Wilkes-Barre, PA

Printed by Robert Baur, 104 Main Street