Belva Lockwood

By Alice Askins, Education Coordinator at Rose Hill Mansion

The Geneva Advertiser reported in October 1884 that “fifty young gentlemen of Geneva, to show their respect for Belva Lockwood and women suffrage, donned petticoats and bustles and gave a torchlight procession. It was the best hit of the season.” So what was going on here?

First, politics in the 19th Century was a source of entertainment. To create enthusiasm for their tickets, party leaders organized parades, barbecues, flag-raisings, and other festivities. Political processions included marchers, brass bands, floats, and flags. Often the parades were at night with torches and fireworks. They were community events.

Second, burlesque parades were well known in 19th Century America. That is burlesque in the sense of grotesque parody, not a striptease. Obligatory militia training fell most heavily on poorer men ( they had to provide their own uniforms and weapons, and take a day off work, losing wages). Resenting this they responded with parades featuring parodies of uniforms and equipment. The Geneva Courier printed a piece about a Connecticut burlesque in July 1833:

Certain gentlemen of New-Haven have recently been moved to burlesque the militia trainings of that state . . . the 1st company, 1st regiment, New-Haven invincibles, paraded . . . armed and equipped as their own taste and sense of military glory directed. Not a musket was to be seen . . . weapons . . . consisted chiefly of hoes, shovels, axes, brooms, cross-bows, &c., &c. . . . The musical instruments seemed to be every thing . . . that would make a noise . . . A description of the unearthly sight . . . cannot be given; it was beyond description. . . . the general’s horse . . . attempted to eat off the grass whiskers of one of the invicibles that stood in front of him.

It will become clear that the Belva Lockwood parades were also burlesques.

Belva Lockwood, ca. 1880

Perhaps Belva is best known today for being the first woman to run for President on an official party ticket. She ran in 1884 and 1888, representing the National Equal Rights Party (Victoria Woodhull had run in 1872, but some discount her campaign because she was younger than the required age of 35). Belva came to her campaigns after many years of work for women’s rights.

She was born Belva Ann Bennett in 1830 in Royalton, New York. Her father was a farmer. When she was 18, she married Uriah McNall, another farmer. When her husband died in 1853, she was left with a three-year-old daughter and no means of support. Belva realized that she needed more education, and attended Genesee Wesleyan Seminary to prepare for college. Most women did not seek higher education at this time, and it was very rare for a widow to do so. She was able to persuade Genesee College, in Lima New York, to admit her. Belva graduated with honors in 1857 and became the headmistress of Lockport Union School. For the next few years, she taught at or was principal for several local girls’ schools. She found, to her frustration, that whether she was a teacher or an administrator, she was paid far less than her male counterparts.

At Genesee College, Belva had been drawn to the law, and studied with a local law professor who offered private classes. Gradually she became determined to focus on law, and in 1866 moved with her daughter to Washington D.C. as she believed there would be good opportunities for lawyers in the capital. To support herself while she pursued her legal studies she opened a co-educational school (which was unusual at the time). In 1868, Belva married Ezekiel Lockwood, a Civil War veteran, Baptist minister, and dentist. They had a daughter who died very young.

Though Ezekiel was progressive and supported Belva’s wish to study law or any other subject that interested her, others were less helpful. Belva struggled to be admitted to a law school. Eventually she entered the National University Law School (now part of George Washington University.) When she had finished her coursework it was another struggle to get the school to grant her a diploma. Without one, she would not be admitted to the D.C. bar. She appealed to President Grant, who was also president ex offcio of the law school. He apparently intervened, and she received her diploma in September 1873. The D.D. Bar admitted her, although several judges told Lockwood they had no confidence in her. During one court appearance a judge told her that God had made women unequal to men, and that she had no right to argue otherwise. He then had her removed from the courtroom. Belva applied to the Court of Claims to represent veterans and their families, but was denied. After the required three years of practice, she applied to the U.S. Supreme Court bar, but was denied there, too.

Despite these setbacks, Belva began to build a practice. Known as an advocate for women’s issues, she spoke on behalf of an 1872 bill for equal pay for federal government employees and testified before Congress in support of legislation to give married women and widows more legal protection. She also drafted a bill allowing all qualified women attorneys to practice in any federal court and from 1874 to 1879 she lobbied Congress to pass it. The bill became law in 1879, and Belva was sworn in as the first woman member of the U.S. Supreme Court bar. Late in 1880, Belva became the first woman lawyer to argue a case before the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing Kaiser v. Stickney and later United States v. Cherokee Nation (she represented the Cherokees.)

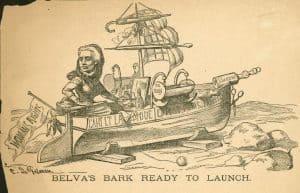

Political Cartoon by C. de Grimm

In her presidential campaigns, Belva represented a third party without a broad base of support. Clearly, she did not have a serious chance of winning the presidency. She received about 4,100 votes in 1884. Since women could not vote, and most newspapers were opposed to her candidacy, 4,100 votes was impressive. I have not been able to discover how many votes she received in 1888. One example of the hostile newspaper coverage was the Atlanta Constitution’s reference to her in 1884 as “old lady Lockwood,” and warning readers of the horrors of “petticoat rule.”

The Geneva papers give us clues that the local Lockwood parades were sarcastic rather than supportive. Apparently a few paraders got carried away with their opinions. The Advertiser stated “some ladies have criticized the Belva Lockwood procession . . . There were one or two men hanging on who deserved knocking down . . . “ This probably means the hangers-on got raunchy.

Shortly after the Geneva parade, there was another in Waterloo. The Advertiser reported:

. . . A most amusing Belva Lockwood parade occurred . . . About seventy young men and boys arrayed themselves in their mothers’ and sisters’ garments, and . . . organized themselves for a grand demonstration. Some were clothed with “Mother Hubbards,” others donned [sic] themselves with large panniers [Mother Hubbards are loose, shapeless dresses; panniers extended 18th-century skirts sideways], while many carried parasols and fanned themselves with as much gusto as if it had not been an exceedingly frosty evening. . . . many houses were finely illuminated to please the boys. Professor Boughton’s residence was nicely lighted, while a grotesque image of Belva appeared at an upper window. The Professor is the Republican candidate for school commissioner, but he likes a joke as well as any one.

The Lockwood parades were popular, and of course repeated in 1888. On October 23 Advertiser reported: “Four years ago a famous parade was made in Geneva by the devoted followers of Belva Lockwood . . . it was the talk of the town for weeks. But there is to be another on Thursday night . . . which will put the first completely in the shade.” The paper followed up on October 30:

The Belva Lockwood parade . . . drew to the streets the largest crowds yet seen during the campaign. In the procession were over two hundred young men . . . The procession formed in Linden street, then took the usual route of all processions through Seneca, Exchange, Lewis, Genesee, Castle, Pulteney, Washington, down Main and Seneca streets, lasting about an hour. So great was the crowd of lookers-on that hundreds gathered around every electric light . . . completely filling the sidewalks and the road . . . When it reached the Franklin House and disbanded, W. P. O’Malley appeared on the balcony and made his appeal in behalf of Belva and low tariff on pins and needles[;] the crowd assembled numbered at least three thousand. . . . The speech lasted about fifteen minutes, mostly in a shrill falsetto, suddenly changing to a sonorous bass. The first change acted like magic on the crowd. . . . it was the best thing of the campaign. . . . To describe the costumes would be impossible. . . . no two were alike, although the Mother Hubbard predominated. There were huge bustles, one six footer was so dressed that he looked like a walking hop-pole in skirts.

The Daily Gazette concurred on October 26:

Genevans wore a broad grin last night, and well they might for the personel [sic] of the Belva Lockwood paraders with their fantastical habiliments was sufficiently ludicrous to make even the dumb animals shake with merriment. In every respect the parade was better and more artistic than any fusilier [sic] parade ever before seen in Western New York . . . [“fusileer parade” is a reference to the militia burlesques] . . . headed by the Hydrant Drum Corps, the Belva constituency, three hundred strong, poured out of Linden . . . their appearance was hailed with a shout of laughter . . . “take the tax off hair pins” was fully concurred in . . . The event put every one in good humor . . .

We often make jokes out of what frightens us, and in the 19th Century the issue of women’s place in society alarmed people who feared change. It took almost another thirty years for the idea of women voting to become familiar and acceptable to New Yorkers. Belva Lockwood had a 43-year career as a lawyer. She died on May 19, 1917, about six months before women gained the vote in her home state of New York.