Student No. 130: Elizabeth Blackwell and Geneva Medical College, Part 1

By Kerry Lippincott, Executive Director

February 3 will mark the 200th birthday of Elizabeth Blackwell. To commemorate her birthday, I would like to share Blackwell’s story and her ties to Geneva in her own words.

February 3 will mark the 200th birthday of Elizabeth Blackwell. To commemorate her birthday, I would like to share Blackwell’s story and her ties to Geneva in her own words.

The third of nine children, Blackwell was born on February 3, 1821 in Bristol, England. At the age of 11 Blackwell immigrated with her family to the United States. The family lived in the New York City area for a few years before Blackwell’s father moved the family to Cincinnati, Ohio. Unfortunately within weeks of their move to Cincinnati her father died leaving the family practically penniless. To support their mother and younger siblings, the five eldest Blackwell children went to work. With few options open to her, Blackwell became a teacher. She, however, did not like teaching. Since she did not want to marry (all five Blackwell sisters did not marry), Blackwell had to support herself. She also wanted to a fulfilling life devoted to service and intellectual challenges. Around 1845 a dying female friend (historians assume it was uterine cancer) explained how her suffering would have eased if she had been treated by a female doctor and suggested Blackwell consider becoming a doctor. Blackwell’s response – I hated everything connected with the body and could not bear the sight of a medical book… My favorite studies were history and metaphysics and the very thought of dwelling on the physical structure of the body and its various ailments filled me with disgust.1

Despite her initial reaction Blackwell did begin to serious consider her friend’s suggestion and began to think that perhaps women, with their maternal instincts, would be better doctors than men –

My mind is fully made up. I have not the slightest hesitation on the subject; the thorough study of medicine I am quite resolved to go through with the horrors and disgusts I have no doubt of vanquishing. I have overcome stronger distastes than any that now remain and feel fully equal to the contest. As to the opinion of people, I don’t care one straw personally… I think I have sufficient hardiness to be entirely unaffected by great agony in such a way as to impair the clearness of thought necessary for bringing relief but I am sure the warmest sympathy would prompt me to relieve suffering to the extent of my power; though I do not think any case would keep me awake at night or that the responsibility would seem too great when I had conscientiously done my best.2

Of all the challenges Blackwell faced, money and men were the primary ones. She figured she needed approximately $3,000 (today that would roughly be $94,000) for tuition, books, and something to live off of. Since she was not independently wealthy she would have to work and save before attending medical school. Men also who controlled the access to the training she required and needed.

Blackwell continued to teach while taking private lessons with doctors and reading various medical texts. By 1847 Blackwell was living in Philadelphia, which was the medical training capital in the United States. Her goal was is to be accepted into a medical school and she sought support from the city’s doctors. There should have been no surprise that she met with resistance. There were two schools of thought – women were intellectually inferior and couldn’t handle medical school or Blackwell would prove that women were actually better doctors than men and provided competition. Options presented to her were either to study in Paris or cross-dress and enter medical school as a man. Not deterred Blackwell began applying to medical schools while continuing private lessons. She wrote

with deep regret I am obliged to say that all the information hitherto obtained serves to show me the impossibility of accomplishing my purpose in America. I find myself rigidly excluded from the regular college routine and there is no thorough course of lectures that can supply its place. The general sentiment of the physicians is strongly opposed to a woman’s intruding herself into the profession; consequently it would be perhaps impossible to obtain private instruction but if that were possible the enormous expense would render it impracticable and where the feelings of profession are strongly enlisted against such a scheme, the museums, libraries, hospitals and all similar aids would be closed against me. But a strong idea, long cherished till it has taken deep roots in the soul and become an all-absorbing duty cannot thus be laid aside. I must accomplish my end. I consider it the noblest and most useful path that I can tread and if one country rejects me I will go to another. 3

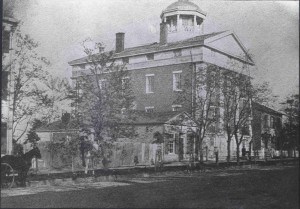

Of the roughly 40 medical schools in the country, Blackwell applied to 29. She received negative responses from all but one – Geneva Medical College. Established in 1834 as a department of Hobart College, the Geneva Medical College had its own building near 493 South Main Street where it had a domed skylight to help illuminate the operation theater. Similar to other medical colleges, prospective students had to be 21 years old with a good moral character; studied three years with a doctor; have knowledge of Latin and natural philosophy (natural sciences); and be able to pay the College’s fees. To graduate, students had to attend two terms of lecture (each term was 16 weeks), write and defend a thesis, pass an oral exam, and pay the $20 graduation fee.

Completed in 1843 the building located around 493 South Main Street housed the Geneva Medical College until 1872. On November 20, 1877 the building burned down.

While the faculty of the Medical College did not want her, they also did not want to offend the doctor who recommended her so they put the question of Blackwell’s admission to the students. As a joke the students approved her admission but there are two versions of the story. In one version the students thought that the faculty was joking so they joined in on the joke by voting to admit Blackwell. According to the other version, students knew that faculty were troubled about Blackwell’s application and thought it would be funny to admit a woman so they did. Either way Blackwell took her acceptance seriously. She arrived in Geneva on November 6, 1847 and registered (though five weeks late) the next day –

Leaving Philadelphia on November 4, I hastened through New York, travelled all night, and reached the little town of Geneva at 11 pm on November 6.

The next day, after a refreshing sleep, I sallied forth for an interview with the dean of the college, enjoying the view of the beautiful lake on which Geneva is situated, notwithstanding the cold, drizzling, windy day. After an interview with the authorities of the college I was duly inscribed on the list as student No. 130, in the medical department of the Geneva University.

I at once established myself in a comfortable boarding-house, in the same street as my college, and three minutes’ walk from it – a beautiful walk along the high bank overlooking the lake. I hung my room with dear mementoes of absent friends and soon with hope and thankful feelings of rest I settled down to study. 4

Blackwell chronicled her first few weeks in her diary

November 9 – My first happy day; I feel really encouraged. The little fat Professor of Anatomy is a capital fellow; certainly I shall love fat men more than lean ones henceforth. He gave just the go-ahead directing impulse needful; he will afford me every advantage, and says I shall graduate with eclat. Then, too, I am glad that they like the notoriety of the thing, and think it a good “spec.”

November 10 – Attended the demonstrator’s evening lecture – very clear – how superior to books! Oh, this is the way to learn! The class behaves very well; and people seem all to grow kind.

November 15 – To-day, a second operation at which I was not allowed to be present. This annoys me. I was quite saddened and discouraged by Dr. Webster requesting me to be absent from some of his demonstrations. I don’t believe it is his wish. I wrote to him hoping to change things.

December 17 – Dr. Webster seemed much pleased with my note, and quite cheered me by his wish to read it to the class to-morrow, saying if they were all actuated by such sentiments the medical class at Geneva would be a very noble one. He could hardly guess how much I needed a little praise. I have no fear of the kind students.

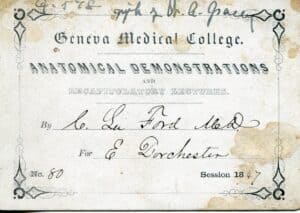

After registering, Geneva Medical College students were given admission tickets for lectures and the dissecting room.

November 20 – In the amphitheatre yesterday a little folded paper dropped on my arms as I was making notes; it looked very much as if there were writing in it, but I shook it off and went on quietly with my notes. Some after-demonstration of a similar kind produced a hiss from the opposite side of the room. I felt also a very light touch on my head, but I guess my quiet manner will soon stop any nonsense.

November 22 – A trying day, and I feel almost worn out, though it was encouraging too, and in some measure a triumph; but ‘tis a terrible ordeal! That dissection was just as much as I could bear. Some of the students blushed, some were hysterical, not one could keep in a smile, and some who I am sure would not hurt my feelings for the world if it depended on them, held down their faces and shook. My delicacy was certainly shocked, and yet the exhibition was in some sense ludicrous. I had to pinch my hand till the blood nearly came, and call on Christ to help me from smiling, for that would have ruined everything; but I sat in grave indifference, though the effort made my heart palpitate most painfully. Dr. Webster, who had perhaps the most trying position, behaved admirably.

November 24 – To-day the Doctor read my not to the class. In this note I told him that I was there as a student with an earnest purpose, and as a student simply be regarded; that the study of anatomy was a most serious one, exciting profound reverence, and the suggestion to absent myself from any lectures seemed to me a grave mistake. I did not wish to do so, but would yield to any wish of the class without hesitation, if it was their desire. I stayed in the ante-room whilst the note was being read. I listened joyfully to the very hearty approbation with which it was received by the class, and then entered the amphitheatre and quietly resumed my place. The Doctor told me he felt quite relieved. .5

What did her fellow students think? According to Blackwell

The behavior of the medical class during the two years that I was with them was admirable. It was that of true Christian gentlemen. I learned that some of them had been inclined to think my application for admission as a hoax, perpetrated at their expense by a rival college. But when the bona-fide student actually appeared they gave me ar manly welcome, and fulfilled to the letter the promise contained in their invitation.

My place in the various lecture-rooms was always kept for me, and I was never in any way molested. Walking down the crowded amphitheatre after the class was seated, no notice was taken of me. Whilst the class waited in one of the large lecture –rooms for the Professor of Practice, groups of wilder students gathered at the windows, which overlooked the grounds of a large normal school for young ladies. The pupils of this institution knew the hour of this lecture, and gathered at their windows for a little fun. Here, peeping from behind the blinds, they responded to the jests and hurrahs of the students. “See the one in pink!” “No, look at the one with a blue tie; she has a note,” &c. – fun suddenly hushed by the entrance of the Professor. Meanwhile I had quietly looked over my notes in the seat always reserved for me, entirely undisturbed by the frolic going on at the window.

My studies in anatomy were most thoughtfully arranged by Dr. Le Ford, who selected four of the steadier students to work with me in the private room of the surgical professor, adjoining the amphitheatre. There we worked evening after evening in the most friendly way, and I gained curious glimpses into the escapades of student life. Being several years older than my companions, they treated me like an elder sister and talked freely together, feeling my friendly sympathy.6

The community, however, was a different story –

I had not the slightest idea of the commotion created by my appearance as a medical student in the little town. Very slowly I perceived that a doctor’s wife at the table avoided any communication with me, and that as I walked backwards and forwards to college the ladies stopped to stare at me, as at a curious animal. I afterwards found that I had so shocked Geneva propriety that the theory was fully established either I was a bad woman, whose designs would gradually become evident or that, being insane, an outbreak of insanity would soon be apparent. Feeling the unfriendliness of the people, though quite unaware of all this gossip, I never walked abroad, but hastening daily to my college as to a sure refuge, I knew when I shut the great doors behind me that I shut out all unkindly criticism and I soon felt perfectly at home amongst my fellow-students. .7

In Part 2 Blackwell’s graduation and medical career will be covered.

To learn more about the Geneva Medical College, join us on February 3 at 1 pm for History Sandwiched In.

For additional programs dedicated to Elizabeth Blackwell on the occasion of her 200th birthday, visit the Hobart and William Smith Colleges website.

Footnotes

[1] Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women Autobiographical Sketches by Dr. Elizabeth. 1895. Schohoken Books, 1977, 27-8.

[2] Ibid., 55-6

[3] Ibid., 62-3

[4] Ibid., 66-7

[5] Ibid., 70-2

[6]Ibid., 73-4

[7] Ibid., 69-70

I want to register for the program on Feb 3 at 1 pm Mary Lawthers

Hi Mary, I signed you up, but for future programs, you can go to historicgeneva.org, click on the program in Current Events, and click Register Here in the article – that will take you to the sign-up window. Thanks! John Marks

Very interesting!!! Thanks for a job well done, keri

Fortunate to have her diary. New book just out about Elizabeth and her sister, also M.D.

I enjoyed the program!

Thank you for including so many nice images of the buildings associated with.the Geneva Medical College.

I research 19th and early 20th century halls and opera houses in our region. On one screen, there was a building in the foreground which had the word Hall painted on itss second story. The image was on the left side of the screen, and I believe it was just before the image of the later Syracuse Medical College. If you know which building that was, I’d be interested in learning more bout it.

Thank you again for an enjoyable program.

Jane Oakes

With a bit of sleuthing we found another version of the image. The sign says Geneva Clothing Hall. The business was at 3 Seneca Street and is advertised in the newspapers. You can see an 1863 example here: https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/lccn/sn83031108/1863-02-13/ed-1/seq-4/