Student No. 130: Elizabeth Blackwell and Geneva Medical College, Part 2

By Kerry Lippincott, Executive Director

Elizabeth Blackwell statue on the campus of Hobart and William Smith Colleges

February 3 marked the 200th birthday of Elizabeth Blackwell. To commemorate her birthday, I would like to share Blackwell’s story and her ties to Geneva in her own words. To commemorate her birthday, last week I shared how Blackwell came to Geneva. This post continues Blackwell’s journey to becoming a doctor in her own words.

Since the term went from October to January, Geneva Medical College students were expected to study independently by observing at a hospital or working alongside a doctor. Blackwell went to Philadelphia between terms where she interned at the Blockley Almshouse (a hospital for the poor). She wrote her mother “I live simple, do my duty, trust in God, and mock at the devil!” Despite the behavior of the male residents, she treated patients and gathered material on typhus that she would use for her graduate thesis. Of her time at Blockley Blackwell wrote:

I returned to Philadelphia to try and arrange for summer study. Whilst seeking medical opportunities I again stayed in Dr. Elder’s family and endeavored to increase my slender finances by disposing of some stories I had written and by obtaining music pupils.

Knowing very little of practical medicine, I finally decided to spend the summer, if possible, studying in the hospital wards of the great Blockley Almshouse of Philadelphia. This enormous institution promised a fine field of observation. I obtained a letter of introduction to Mr. Gilpin, one of the directors of the almshouse.

He received me most kindly, but informed me that the institution was so dominated by party feeling that if he, as a Whig, should bring forward my application for admission, it would be inevitably opposed by the other two parties – viz. the Democrats and the Native Americans [the Know Nothings]. He said that my only chance of admission lay in securing the support of each of those parties, without referring in any way to the other rival parties. I accordingly undertook my sole act of ‘lobbying.’ I interviewed each political leader with favourable results, and then sent in my petition to the first Board meeting – when, lo! a unique scene took place; all were prepared to fight in my behalf, but there was no one to fight! I was unanimously admitted to reside in the hospital. This unanimity, I was afterwards assured, was quite without precedent in the records of the institution.

On entering the Blockley Almshouse, a large room on the third floor had been appropriated to my use. It was in the women’s syphilitic department, the most unruly part of the institution. It was thought that my residence there might act as a check on the very disorderly inmates. My presence was mystery to these poor creatures. I used to hear stealthy steps approach and pause at my door, evidently curious to know what I was about. So I placed my table with the books and papers on which I was engaged directly in a line with the keyhole; and there I worked in view of any who chose to investigate the proceedings of the mysterious stranger. 1

She continued –

During my residence at Blockley, the medical head of the hospital, Dr. Benedict, was most kind, and gave me every facility in his power. I had free entry to all the women’s wards, and was soon on good terms with the nurses. But the young resident physicians, unlike their chief, were not friendly. When I walked into the wards they walked out. They ceased to write the diagnosis and treatment of patients on the card at the head of each bed, which had hitherto been the custom, thus throwing me entirely on my own resources for clinical study.

During the summer of 1848 the famine fever was raging in Ireland. Multitudes of emigrants were attacked with fever whilst crossing the ocean, and so many were brought to Blockley that it was difficult to provide accommodation for them, many being laid on beds on the floor. But this terrible epidemic furnished an impressive object-lesson, and I chose this form of typhus as the subject of my graduation thesis, studying in the midst of the poor dying sufferers who crowded the hospital wards. 2

By October 1848 Blackwell returned to Geneva for her second term –

By this time the genuine character of my medical studies was fully established.

Had I been at leisure to seek social acquaintance I might have been cordially welcomed. But my time was anxiously and engrossingly occupied with studies and the approaching examinations. I lived in my room and my college, and the outside world made little impression on me. 3

In addition to classes, Blackwell and other prospective graduates had to defend their thesis and take oral exams. On January 19, Blackwell wrote about her exams

I, as first on the list of candidates, passed through the usual examinations, presented my certificates, received the testimony of satisfaction from the faculty, whose recommendation will procure me the diploma next Tuesday. Now, though the examinations were not very formidable, still the anxiety and effort were as great as if everything were at stake, and when I came from the room and joined the other candidates who were anxiously awaiting their turn, my face burned, my whole being was excited, but a great load was lifted from my mind. The students received me with applause – they all seem to like me and I believe I shall receive my degree with their united approval; a generous and chivalric feeling having conquered any little feelings of jealousy. 4

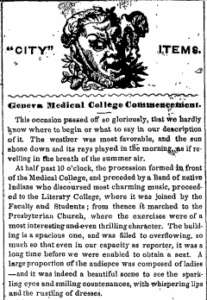

On January 23, 1849 Blackwell participated in the graduation ceremony with some modifications. First, she chose not to wear the traditional robe of a graduate. In its place she bought a new black silk dress trimmed at the cuff and collar with white lace. She hesitated to spend the money but didn’t want as she explained to her family “to disgrace womankind, the college or the Blackwells by presenting myself in a shabby gown.” Second, she did not walk in the procession. Typically graduates walked from the Medical College to the Presbyterian Church along the way the President, dean, and faculty joined them. Blackwell refused on the grounds that it was unladylike to march in processions. Instead, she entered with her brother Henry (the only family member to attend the ceremony) and sat quietly until her name was called. Once Blackwell received her diploma she sat with the other sixteen graduates. She recorded the day in her journal –

I must record my first entrance into public life – ‘twas bright and beautiful and very gratifying. Great curiosity was felt. As I entered and sat in the church I gave on thought to friends, and then thought only of the Holy One. After the degree had been conferred on the others, I was called up alone to the platform. The President, in full academical costume, rose as I came on the stage, and, going through the usual formula of a short Latin address, presented me my diploma. I said: ‘Sir, I thank you; it shall be the effort of my life, with the help of Most High, to shed honour on my diploma.’ The audience applauded, but their presence was little to me. I was filled with a sense of the grandeur of a holy life, with high resolves for the future. As I came down, George Field opened the door of the front row, and I was much touched by the graduates making room for me, and insisting that I should sit with them for the remainder of the exercises. Most gladly I obeyed the friendly invitation, feeling more thoroughly at home in the midst of these true-hearted young men than anywhere else in the town. I heard little of what was said; my whole soul was absorbed in heavenly communion. I felt the angels around me. Dr. Lee gave the valedictory address; he surprised me by the strong and beautiful way in which he alluded to the event. I felt encouraged, strengthened to be greatly good. As I stood at the door the faculty all most kindly wished me good-bye, and Dr. Hale and Bishop DeLancey shook hands and congratulated me. All the ladies collected in the entry, and let me pass between their ranks; and several spoke me most kindly.

For the next few hours, before I left by train, my room was thronged by visitors. I was glad of the sudden conversion thus shown, but my past experience had given me as useful and permanent lesson at the outset of life as to the very shallow nature of popularity. 5

(Read an account of Blackwell’s graduation by an audience member)

Blackwell’s goal was to become a surgeon. She may have had her medical degree but she need more training before establishing her own practice –

I knew, however, that a first step only had been taken. Although popular sanction had been gained for the innovation, and a full recognized status secured, yet much more medical experience than I possessed was needed before the serious responsibilities of practice could be justly met. Returning, therefore, to Philadelphia, I endeavored still to continue my studies. I politely received by the heads of the profession in Philadelphia as a professional sister…

I felt, however, keenly the need of much wider opportunities for study then were open to women in America. Whilst considering this problem I received an invitation from one of my cousins, then visiting America, to return with him to England, and endeavor to spend some time in European study before engaging in practice in America. 6

In Paris La Maternite (a hospital where young women trained to become midwives) was the only institution that would accept her as a student. Blackwell simply adjusted her goal – become an accomplished obstetrician then become a surgeon. During her second term tragedy struck. On November 4, 1849, while treating an infant with neonatal conjunctivitis, Blackwell contaminated one of her eyes. She would not only lose sight in that eye but it ultimately had to be removed. Though she lost hope of becoming a surgeon Blackwell still wanted to practice medicine. After months of recovery, she was admitted to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London as a student –

There are so many physicians and surgeons, so many wards, and all so exceedingly busy that I have not yet got the run of the place; but the medical wards are thrown open, unreservedly to me, wither to follow the physicians’ visits or for private study. ‘ later, I shall attend the surgical wards. At first no one knew how to regard me. Some thought I must be an extraordinary intellect, overflowing with knowledge; others a queer eccentric woman and no one seemed to understand that I was quiet sensible person who had acquired a small amount of medical knowledge and who wished by patient observation and study to acquire considerable more.7

During the summer of 1851 Blackwell returned to the United States and settled in New York City. When she couldn’t find work in any of the city’s hospitals or clinics she set up her own practice. She still struggled getting patients and working with colleagues. In one of her early cases Blackwell was treating an elderly woman with pneumonia and called in another doctor for a consultation. He, she wrote –

began to walk about the room in some agitation, exclaiming, “a most extraordinary case. Such a one never happened to me before. I really do not know what to do!’… it was a clear case of pneumonia and of no unusual degree of danger until at last I discovered that his perplexity related to me not to the patient and to the propriety of consulting with a lady physician. I was both amused and relieved.8

With few loyal patients, to support herself Blackwell began giving lectures and writing about was the basis of her practice – sanitation as the key to health. With a motto of “prevention is better than the cure” what she promoted is considered common sense today – a balanced diet, hygiene, adequate exercise, and self-education. She believed that illnesses plaguing women could be avoided if women better understood their bodies.

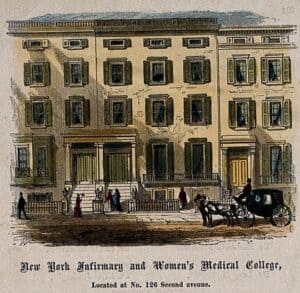

New York Infirmary And Women’s Medical College

Blackwell continued to fight for opportunities for women to learn and practice medicine. In 1853 she opened a small clinic, where people could receive treatment for little or no cost. A few years later the dispensary became the New York Infirmary for Women and Children (now New York Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital). A hospital and outpatient clinic, the infirmary was for and run by women (women served on the board, on the executive committee and as the attending doctors). In 1868 she co-founded the Woman’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary making it the third medical college for women in the United States. A year later Blackwell moved permanently to England where she became the first woman to be included in the medical register (the official list of medical practitioners in England). In 1874 she co-founded the London School of Medicine for Women (now the University College of London Medical School. Though she retired in 1877, she traveled, wrote books and advocated for a variety of reforms including family planning, sex education for children, hygiene, sanitation, preventative medicine, and, of course, the need for more female doctors.

When Blackwell died on May 31, 1910 there were 7,399 female doctors in the United States. Today, one hundred and twenty-years after Blackwell received her degree, there are over 359,000 women practicing medicine in the United States.

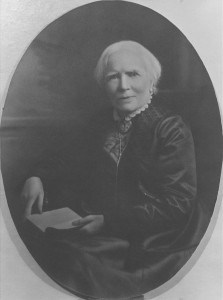

Elizabeth Blackwell

Recommended books

New Biography about Elizabeth Blackwell and her sister Emily – The Doctors Blackwell: How Two Pioneering Sisters Brought Medicine to Women and Women to Medicine by Janice P. Nimura

Histories of Women Doctors in the United States

Send Us a Lady Physician: Women Doctors in America, 1835-1920 by Ruth Abram

Women Medical Doctors in the United States before the Civil War: A Biographical Dictionary by Edward C. Atwater

Sympathy and Science: Women Physicians in American Medicine by Regina Morantz-Sanchez

Footnote

[1] Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women Autobiographical Sketches by Dr. Elizabeth. 1895. Schohoken Books, 76-77

[2] Ibid., 80-1

[3] Ibid., 83

[4] Ibid., 84-5

[5] Ibid., 86-7

[6] Ibid., 92-94

[7] Ibid., 170

[8] Ibid., 194-5

Dr. Blackwell certainly fought an up hill battle to prove herself. With On The Job training

being the primary way of learning, she had to work twice as much as her counterparts.

Women today are still having to prove themselves.