A Survivor of the Civil War: The Letters of James Pressley Fulton

By Becky Chapin, Archivist

I’ve read a lot about the Civil War since I first learned about it. My family visited several sites on our vacations over the years. But nothing brings the experience of being in the middle of history more to the forefront than reading primary source materials. When writing the finding aid for the James Fulton Papers, I spent hours reliving his experiences as a soldier in the Union Army. 159 years later, his story deeply impacted me, and I wanted to share some highlights from his letters home.

James Pressley Fulton was born on August 17, 1843 in Seneca, NY. In July 1862, around age 17, James enlisted in the New York 126th Company D at Camp Swift in Geneva, NY.

On August 20, 1862, James wrote his first letter home as a soldier stationed in Camp Swift while he was awaiting his next orders. Just days later, he is writing from Bolivar Heights, Virginia. He told his parents he visited the place where abolitionist John Brown caged himself at Harper’s Ferry in 1859. When James visited the spot, the area was occupied by Rebel prisoners.

On September 3, James writes “I have not yet been in any very severely Contested Engagements but still remain at Harper’s Ferry…events seem to Indicate that we shall have to prepare for the Field as soon as possible.” He remarked on how the area bears sad traces of war from the rebels burning buildings and fences for fuel, how much drilling he’s doing, and how he saw several hundred paroled released prisoners from the rebel army passing by on their way to Annapolis.

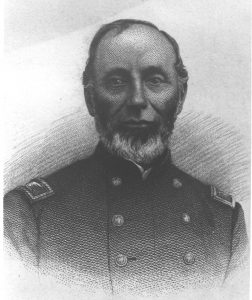

On September 12, the Battle of Harpers Ferry began. James fought in this battle and next writes home on September 22. James was among the 11,000 Union troops captured by “Stonewall” Jackson’s Confederate Army. He writes a detailed account of his experience in the battle, his colonel (Eliakim Sherrill) being shot, then his company were surrounded and forced to hoist a white flag of surrender. In total, he believed there were over 100 men killed; one was killed and 7-8 wounded in his company. Upon being taken prisoner, they were set to march to Annapolis where he was released on parole, ending his letter “JPF Paroled Prisoner of War.”

James marched from Annapolis to Camp Douglas just outside of Chicago, Illinois, where he remained a paroled prisoner until December. Once they arrived on September 28, the prisoners slept on the ground overnight before being allowed barracks. Camp Douglas had been occupied by about 9,000 rebel prisoners for the summer of 1862; they had left the barracks dirty and full of lice, so the Union prisoners had to clean everything before they could settle in. Being paroled, James and other prisoners were allowed to go to Chicago to visit friends and relatives.

On October 20, James writes he heard Judge Folger and the War Committee were doing their best to get the Geneva men home. So many men were getting sick, one of the wounded in the company had died, and the Colonel was getting better which was good because the men liked Sherrill more than his replacement, Baird. In November, Baird is discharged “for being a disgrace.”

By December 3, James was released and his company are encamped in Arlington. The new year brought the company to Union Mills but no pay for James for many days. The hospitals were full of sick men, one or two buried or sent home dead every day, and measles is spreading through the camp. Rebels would approach their camp and rip out telegraph lines, those on guard would march out to drive them back.

to be a soldier It sometimes makes me Feel all the Triels and Hard ships Incident to a soldiers Life with Fortitude that the cause In which we are engaged Is a just and holy Cause and that It Is the duty of every Man to unite all his energies to crush out so wicked and causeless a Rebellion which has so disturbed the hopes and prospects of our once bright and happy Country and on the other hand I often feel Meloncoly to think of the amount of Innocent blood that has been sacrificed so many soldiers graves have been filled and still the great end which we are struggling may after all not be accomplished yet I still hope and trust In the that the Providence of god will work out all things for the best. (January 22, 1863)

In a letter to his sister on February 21, he laments a lack of word from home with no letters in over three weeks. His company continues picketing as the cavalry is occasionally ambushed by guerilla and rebel soldiers. James reports that Seneca resident James Barden dies in his February 25th letter; Barden, 19 years old, died of a disease along with several others from the same company. By mid-April, the company have marched to Centreville and are stationed at the house of someone who pretended to be a Union man but fled to join a group of guerillas.

On May 21, writing his sister, James reflects on his experience at Harper’s Ferry, about seeing Stonewall Jackson as he passed by on his horse, and about where he is now. “Often a sense of Solitude and Loneliness and a Meloncoly Feeling creeps over me As I think of the time and changes which Providence has wrought.”

But midst the crowd the hum

And shack of Men

To roam along the World Tired Denisen

With none who Bless us

None whom we can Bless

None with kindred consciousness

Endured This Is to be alone

This is Solitude. -poem written by James P Fulton.

The company reaches Gettysburg in late June and joined in the skirmishes near Gettysburg. They lose a captain, an unknown number of men, and 30 were wounded. The color guard were shot dead nearby, they drove the Rebels away, “stood their ground Nobly Never Flinching,” until Col. Williard was shot dead and the Sgt. Major was killed. They stopped fighting overnight and took cover in the woods, the next day enduring many shells and sharpshooters before capturing about 2,000 prisoners.

On July 16, James wrote from Harper’s Ferry. Lee’s great raid on Pennsylvania cost him 10,000 men; 20 killed or wounded in our company during the battle of Gettysburg. “I hope this Cruel War will be Over and I can return home safe.” The company marches toward Warrington Junction where they are encamped by August 19. William Baird, who was dishonorably discharged at Maryland Heights, rejoins the regiment as a Lt. Col. and James asks how “rascals” get ahead when there are smart, “moral” men in our company who are overlooked. James, who had not eaten in two days, ate biscuits from the knapsack of a dead Rebel.

On July 16, James wrote from Harper’s Ferry. Lee’s great raid on Pennsylvania cost him 10,000 men; 20 killed or wounded in our company during the battle of Gettysburg. “I hope this Cruel War will be Over and I can return home safe.” The company marches toward Warrington Junction where they are encamped by August 19. William Baird, who was dishonorably discharged at Maryland Heights, rejoins the regiment as a Lt. Col. and James asks how “rascals” get ahead when there are smart, “moral” men in our company who are overlooked. James, who had not eaten in two days, ate biscuits from the knapsack of a dead Rebel.

On September 2, James notes it has been a year since he left home alongside 1,011 men. Now the number is 300, many in hospital or dead. People at home read about the war but “they do not know what it cost to gain these victorys.” For the next couple of months, his company moves around, engaging in a few skirmishes between Culpeper, Centreville, Turkey Run, and Chancellorsville before settling in the winter quarters of Stevensburg.

During the 1863-1864 winter, James contemplates going to officer’s school, wanting to apply for the Free Military School of Philadelphia. He asks how the family feels about him reenlisting.

On June 11, James writes from a field hospital near Parkess Store, his first letter home since April 28. His company engaged in the Battle of the Wilderness on May 5 and he was badly wounded, either on the 5 or 6, with a bone fracture in the thigh and taken prisoner. It takes months until he is able to write home and tell them how he received his injury.

On October 13, 1864, James writes about his experience on the battlefield. He was wounded about 12 AM on May 6, laying overnight among the dead and wounded. Rebels flanked them, began to strip the dead and wounded of clothing and valuables. From James they took two memorandum books which contained experiences he had been writing down throughout the war, but they didn’t take much money. When a man tried to take the vest he was wearing, his protests drew the attention of officers who had James moved off the field via ambulance. He laid on the ground in the hot sun for 10 days among the wounded, about half of whom would die. He wasn’t fed much.

He remembers the long, hungry hours of pain and suffering. Eventually he was seen by Dr. Lewis of the Confederate Army who said James would have a hard time if he lived. On October 5, he had been moved to Richmond and was a paroled prisoner again. Now he was at the General Hospital in Annapolis, his wound healed but unable to bear weight on his leg.

James’ last letter is dated March 8, 1865 where he talks about being discharged. After his return home, James wrote his Reminiscences of the War in a notebook, reconstructing the memorandum books that were stolen from him.

He married Sarah M. Frost on May 27, 1874, and they had one daughter, Maud. He was Postmaster of Stanley, New York for many years.

James P. Fulton died on February 19, 1919 and was buried in the New Number Nine Cemetery in Seneca.

Numbers are based on James’ letters and may not reflect the actual casualty numbers known today. For more on Geneva’s involvement in the Civil War, check out our exhibit from 2015-2016: “Now is the Time of Our Country’s Need”: Geneva and the Civil War. To read summaries of James’ correspondence, view the finding aid at EmpireADC.

This first hand account was very interesting. I would like to understand what paroled meant. It seems the paroled soldiers returned to fighting for their side of the conflict.

I’ve added a link above to an explanation of parole, but essentially they were held in their own territory with the promise that they would not engage in fighting again until exchanged for enemy prisoners.