The Pre-Emption Line, Part 1

By John Marks, Curator of Collections and Exhibits

Recently a friend asked me, “Don’t you get tired of looking at all that old stuff?” No, I don’t, in part because new audiences ask me about the old stuff. About 15 years ago I spent time learning about the Pre-Emption Line and created a program on it. This month two groups asked me to give the program, and I revisited the subject.

Doing more research on an event makes it more complicated, never less. The challenge is to add information to give a complete history, without making a presentation longer or more confusing. However, discussing the Pre-Emption Line needs a brief background of land agreements between the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and New York.

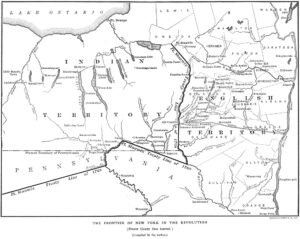

In a sentence, New York always wanted more land, and the Haudenosaunee didn’t want to give it up. The 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix drew a line beyond which colonists could not settle. However, New York could buy land west of the line in the future, and they did.

In 1776 the new nation was cash poor. Congress passed a law that Revolutionary soldiers or their survivors would receive land as payment for service. In 1781 New York authorized a “military tract” and increased the land bounties offered by Congress. A private would receive 500 acres, escalating to 5,500 acres for a major general. Although land wasn’t given to veterans until 1791, the western boundary of New York was extended to the east side of Seneca Lake. Seneca County Historian Walter Gable wrote a detailed summary of the Military Tract.

The states’ money problems continued after the Revolution ended in 1783 with the Treaty of Paris. Looking for a way to raise money, Massachusetts claimed New York land west of Seneca Lake, and the right to sell it, for itself. The basis was Massachusetts’ 1629 land grant from King Charles I of England which declared the western border to run to the next sea. New York fought the claim and the case was presented to Congress, then the Supreme Court. No one wanted to touch it.

In 1786 the two states met in Hartford, Connecticut to resolve the dispute. The resulting Treaty of Hartford stated that Massachusetts would receive the pre-emptive right of the soil, that is, the right to offer the land for sale after the Indian title had been cleared. (The definition of pre-emption is, “The right to purchase something, especially government-owned land, before others; Acquisition or appropriation of something beforehand.”) After the land was sold, it would be part of New York. The Pre-Emption Line marking the eastern boundary of Massachusetts’s claim would run north from the 82nd milestone on the Pennsylvania-New York state line to Lake Ontario.

Massachusetts investors lined up to buy the right to sell the land. Oliver Phelps formed an association of other investors to approach the state legislature, but Nathaniel Gorham beat them to it. The two men joined forces and in 1787 went to the legislature to buy the land. The state senate voted down the proposal, giving some senators time to join the Phelps and Gorham association.

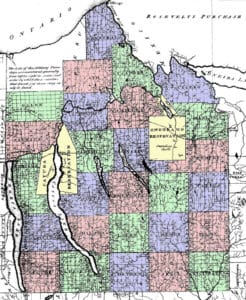

In 1788, Massachusetts enacted legislation to sell Phelps and Gorham six

million acres in western New York State for one million dollars in the depreciated state currency. Before they could begin selling land, Phelps and Gorham had to negotiate with the Haudenosaunee for title to the land and survey the Pre-Emption Line and interior townships.

Next month we’ll look at competitors for the western lands and surveying the Pre-Emption Line.

Additional Pre-Emption Line Blog Articles